The unintended consequences of taking misinformative electoral content off the air

The second of the twelve tasks Hercules had to face on his journey was slaying the Hydra, the seven-headed half-serpentine monster. This was a tricky assignment not only because of the monster's fatal poison or huge size, but because of its regenerative powers: if one head was cut off, two heads appeared from the cut.

Based on the former Brazilian presidential elections, this article provides some insights on how the regulatory strategy of taking online speeches off the air to counter electoral misinformation might be similar to the Hydra situation. That is: it might backfire.

Challenges of taking misinformative content off the air

The regulatory removal of misinformative content as a strategy to protect democratic institutions' legitimacy may, in fact, contribute to the perception of this regulation as illegitimate. This article highlights two intertwined challenges that can explain why this can occur.

The first one is the fact that the far right used misinformation against democratic institutions as a campaign strategy and, therefore, the removal of such content raised partiality and censorship accusations. The second one regards the nature of misinformation as a type of conspiracy theory: prohibiting it may feed the premise that the theory is not only true but an inconvenient truth for the government.

The 2022 Brazilian Presidential Election Background

One of the biggest challenges of the 2022 Brazil Presidential Election was to counter the production and circulation of misinformation. This did not come as a surprise: in the 2018 elections, misinformation had already played a very important role, demanding some reaction from the Electoral Justice. Thus, four years later, the same justice braced itself with regulatory and policy changes and improvements in order to have the appropriate tools to face this battle.

Provided by the electoral legislation, one of the most important tools available for Electoral Justice in 2018 was the competence to analyze online posts brought by complaints from entitled actors and remove the ones that it deemed to be "knowingly untrue" (Article 22, Resolution 23.551/2017). In 2022 this core strategy was replicated, but with a boost: it also became forbidden to disclose or share facts that were "[...] seriously out of context that affect the integrity of the electoral process, including the voting, counting and totaling of votes, and the electoral court". That is, the Electoral Justice could also order the removal off the air of contents that fell under these categories.

As predicted, in the presidential field, the dispute was concentrated between two candidates: Lula, representing the left and center, and Jair Bolsonaro, the former president, as the face of the more conservative right wing.

Challenge 1: "Censorship!"

According to the report produced by Igarapé Institute - which summarizes electoral misinformation trends identified through the monitoring of social media during the Brazilian elections -, the far right was more successful in engaging and spreading messages via social networks. And just like a global-south version of Trump's "the elections are rigged", Bolsonaro's campaign was highly dependent on the production and spread of misinformation. Not only against the other candidates, but mostly - and more dangerously - against the democratic system, Electoral Justice, and the Supreme Court. This leads us to the first challenge: partiality and censorship claims against the Electoral Justice.

Since more antidemocratic misinformation came from the far-right, the Electoral Justice was naturally more severe towards Bolsonaro and his supporters. And here lies the regulatory trap: the more pro-Bolsonaro content was removed, the louder were the accusations of the judiciary's censorship and partiality. As Igarapé report points out:

"The judicial bodies in charge of regulating elections acted firmly and in a timely fashion as the turbulent electoral dispute ran its course. This led to one of the most resonant online sub-narratives: the far right outcry over alleged moves of “media regulation”." (Igarapé, 2023: 17)

This regulatory challenge can be framed as the trade-off between strict enforcement of the rule and the risk of the perception of the regulation as illegitimate. Simply put: in theory, the more far-right content was removed, the more the Electoral Justice worked towards an online environment clean from content questioning the legitimacy of democratic institutions. In practice, the more far-right content was removed, the more the Electoral Justice itself had its legitimacy questioned.

Challenge 2: "They don't want us to spread the truth!"

Muirhead and Rosenblum, in their book A Lot of People are Saying, present new conspiracism as one of the current major threats against democracy, since it is able to strike down the basic institutions of democracy, disorienting us and distorting public life (Muirhead & Rosenblum, 2020). Trump's "the elections are rigged" is the first example given to define what is covered by the new conspiracism phenomenon.

In other words, while the authors agree with the loud and clear statement that fake news damages democracy, they are moving away from the trend that describes them as "lies". Instead, they circumscribe the issue within the field of conspiracism, but with an update from the classic conspiracy theories. The authors develop the concept of "conspiracy without the theory" to explain what is going on.

"The new conspiracism is something different. There is no punctilious demand for proofs, no exhaustive amassing of evidence, no dots revealed to form a pattern, no close examination of the operators plotting in the shadows. [...] What validates the new conspiracism is not evidence but repetition. [...] The new conspiracism—all accusation, no evidence—substitutes social validation for scientific validation: if a lot of people are saying it, to use Trump’s signature phrase, then it is true enough.” (Muirhead & Rosenblum, 2020: 19)

This concept is relevant for a number of reasons. However, for this article's purpose, one of them is worth highlighting: conspiracism as a genre (the old and the new) presents itself as the discovery of the "actual truth" among the public "lies" told by the mainstream institutions (traditional media and government). In this sense, conspiracy with and without the theory carries the "satisfaction of knowingness" (Muirhead & Rosenblum, 2020: 52).

"Conspiracy theorists see themselves as having privileged access to, and knowledge of, what they think is reality. This means possessing knowledge that others lack "which constitutes a buffer that partially protects believers against the potentially disastrous effects of disconfirming evidence" (Barkun, 2016)." (van Geffen, 2019)

In this sense, those who believe and spread conspiracy without theories see themselves as “[...] an elite, a 'cognoscenti' [...]. like the inner circle of an esoteric group or sect." (Muirhead & Rosenblum, 2020: 52).

This is relevant because if the core of conspiracy theories is to uncover the truth that the mainstream is trying to hide for whatever reasons, then the more the mainstream institutions suppress the conspiracists' speeches, the more credibility it gives to their argument.

Framing misinformation under the new conspiracy theory leads us to a better understanding of why the strategy of taking content off social networks may backfire and actually empower the conspiracy theory itself.

Under the conspiracists logic, the more the government suppresses it, the more it seems to be true. And this may lead to the perception that breaking the State's rule is a duty for society to be able to know "the truth".

Survey among electors

These two challenges back up this article's concern: the inefficiency of the regulatory strategy of taking content off social media to counter electoral misinformation. The answers collected from a survey conducted with Brazilian electors also give reasons for this concern to be taken seriously.

The survey aimed at understanding how ideology might relate to the perception of the legitimacy of misinformation regulation. Through direct multiple-choice questions, it collected voters' perceptions about the legitimacy of content removal to counter misinformation. The findings are based on 80 answers: 51 electors voted for Lula and 29 voted for Bolsonaro.

Although the research has some limitations that impair it from being representative of Brazilian opinion as a whole, it does point to important trends in terms of ideology and electors' perceptions towards misinformation regulation. The next session focuses on the main findings, but you can check all the questions and answers here.

Findings

Overall, the findings confirm the hypothesis that the removal of misinformative content as a government strategy to protect democratic institutions' legitimacy may, in fact, contribute to the perception of this regulation as illegitimate. This is shown by the three following main trends.

Says who?

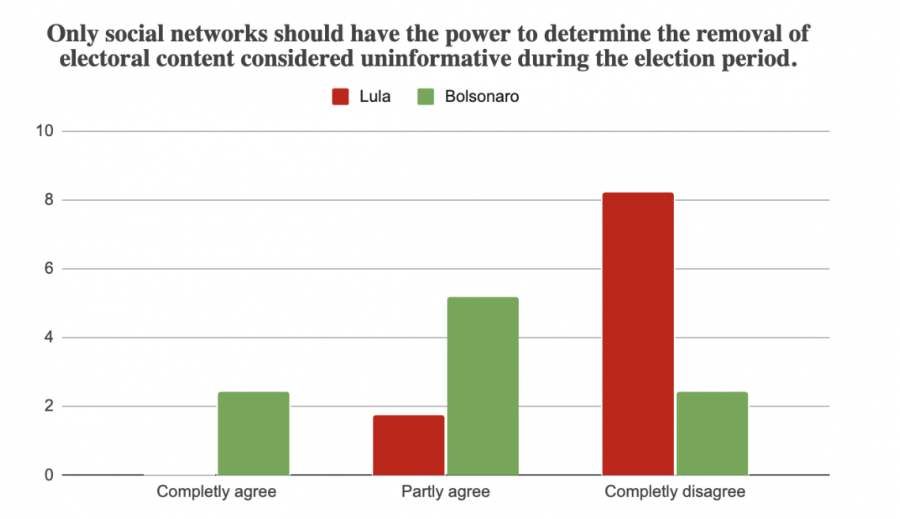

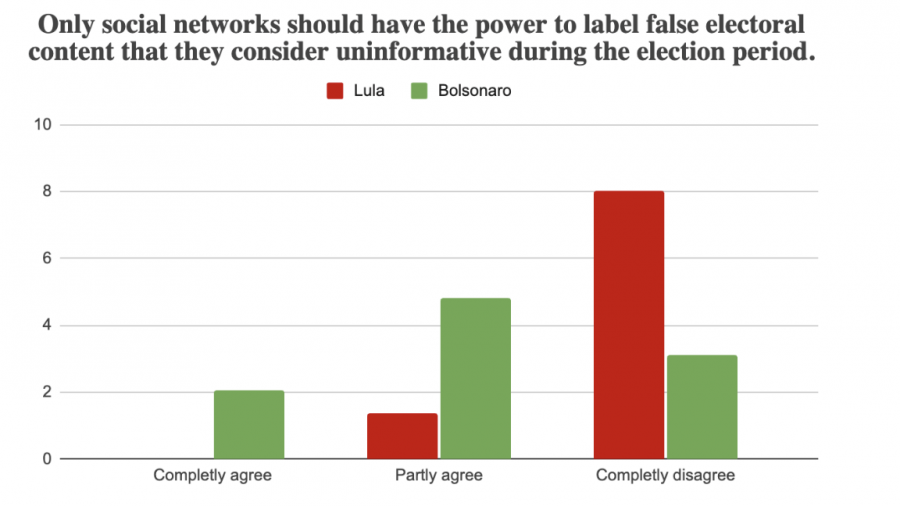

As can be seen from graphics 1 and 2, 80% of Lula's voters do not believe that the power to regulate misinformation (neither by removing the content nor by labeling it as false) should only belong to the social network's hand. The majority of Bolsonaro's voters, on the other hand, agree at least to some extent that this power should rest solely within the platform's hands.

Graphic 1

Graphic 2

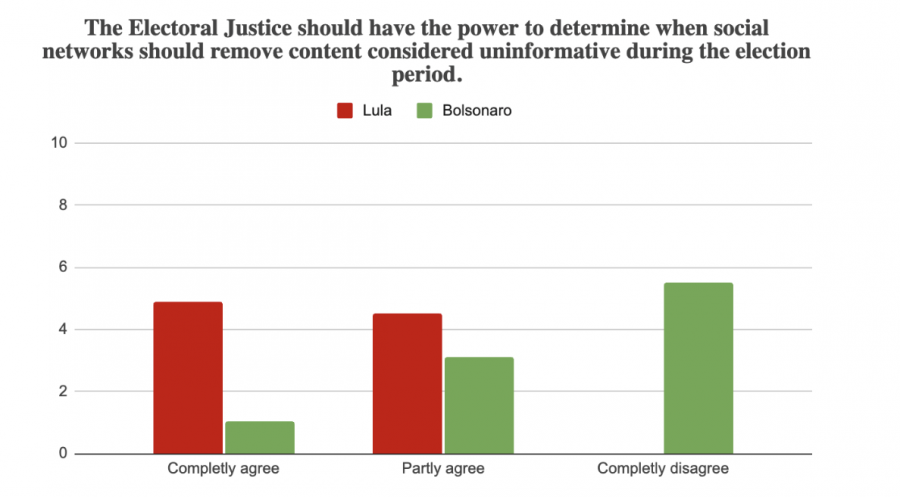

Graphic 3 (below) shows that, in general, Lula's voters agree to some extent that the Electoral Justice should have this regulatory power, while almost half of Bolsonaro's voters completely disagree.

Graphic 3

Consequently, in regards to who regulates, the research allows for the conclusion that those who voted for Bolsonaro perceive the regulation as more legitimate if it comes from the social platforms than from the Electoral Justice.

Potato, Pothato?

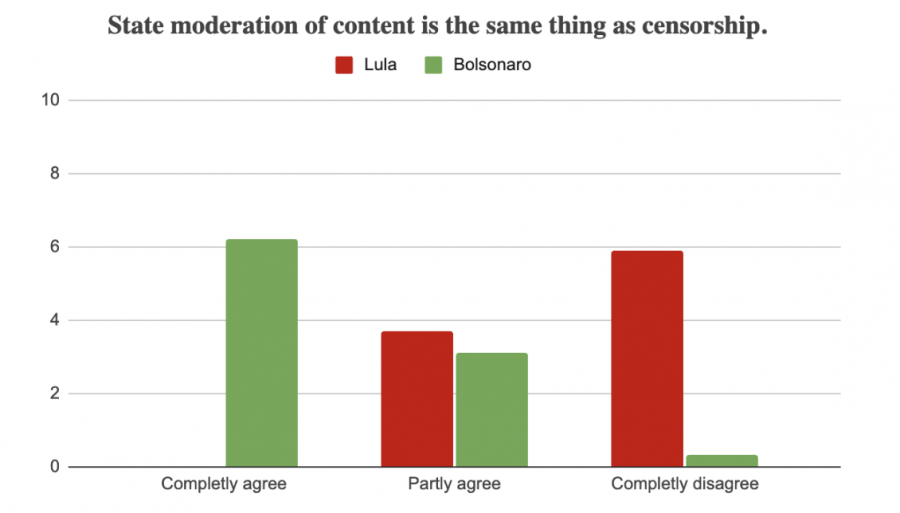

The research also shows that the majority of those who voted for Bolsonaro understand the State's content moderation as censorship, while the majority of Lula's voters disagree completely with this statement. This can be seen in the graphic 4, below:

Graphic 4

This finding can help explain the conclusion stated in the topic above. It may be that Bolsonaro voters perceive State content regulation as more illegitimate than if it came from the social platforms themselves because when the State is the author of such regulations, it corresponds to censorship. In other words, State interference in speech is seen as illegitimate because it is directly associated with censorship.

The lesser of two evils?

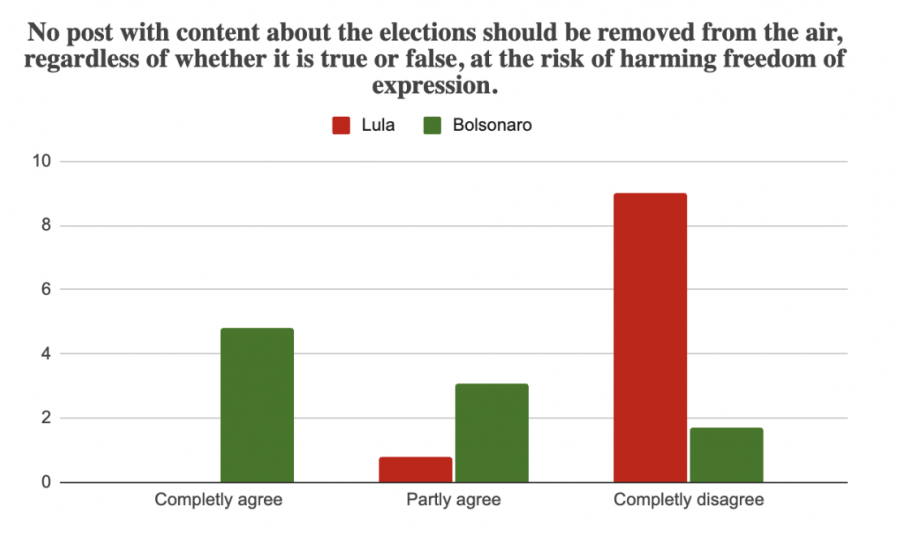

The majority of Bolsonaro voters agree to some extent that posts with content about elections should not be removed from the air, regardless of whether their content is true or false because there is a risk of harming freedom of expression. Almost the entirety of Lula voters completely disagree with this statement. This can be seen in graphic 5:

Graphic 5

This allows for the conclusion that for Bolsonaro voters, freedom of expression is not harmed by the circulation of fake electoral content. It seems that, for them, freedom of expression is most harmed when the speech is removed from circulation. It is important to highlight that this trend is not circumscribed to national borders, but seems to indicate a worldwide pattern among the far-right (Igarapé, 2023:8)

All in all

If, as shown throughout the article, the majority of fake news comes from the right wing and this is the portion of society that is skeptical of the State's content moderation, then the Electoral Justice attempts to regulate misinformation by ordering content removal might be more harmful than beneficial. That is, it may be perceived as illegitimate precisely by those who most need to comply with it.

If we accept that the misinformation phenomenon can be seen as a part of a new conspiracism movement (conspiracy without the theory), as proposed by Muirhead and Rosenblum, then the situation is yet more serious. Since the nature of conspiracism is to reveal what "they" want hidden, the more one prohibits it from being said, the more it seems to be true, as the effort to remove it from circulation may be mistaken for an effort to keep the truth hidden from the masses.

This article is not proposing how things ought to be, but rather describing things as they are - whether we like it or not. This means that, even if we would like for all electoral misinformation to be banned from the face of the earth and, therefore, root for the government to be able to take it all off online platforms, what this article aims to show is that this strategy may not help as much as we would expect it to.

Content removal is a harsh measure for it gives the opportunity for simplistic censorship narratives to flourish. This article, then, suggests two main courses of action - both of which were already implemented by the Brazilian Electoral Justice in the 2022 Presidential Elections.

The first one is to not rely solely on content removal strategies, but to diversify the regulation into different types, such as refuting specific rumors, investing in pre-bunking techniques, and focusing on prohibiting inauthentic behavior instead of content itself (Monteiro et al., 2022). The second one: if content removal is going to be a part of the regulatory fight against electoral disinformation, then a transparent collaboration policy between the State and social platforms could mitigate this censorship narrative.

All in all, the ultimate goal is, of course, to kill the Hydra. This article suggests that frantically cutting all of its heads may not help much. We should maybe try to understand how the monster behaves and observe its particularities and weak spots. Even if we decide that cutting the head is the way to go, let's at least take a step back and try to find the "immortal head", the one that actually makes sense to cut off.

References

Geffen, R. van. (2019, September 25). Conspiracy theories in Digital Culture. Diggit Magazine.

Lima Monteiro, A. P., Brito Cruz, F., Fonteles da Silveira, J., & Valente, M. (2022, July 19). Armadilhas e Caminhos na Regulação da Moderação de conteúdo (traps and ways forward in regulating content moderation).

Muirhead, R., & Rosenblum, N. L. (2020). A lot of people are saying: The new conspiracism and the assault on democracy. Princeton University Press.

Taboada, C., Assis, M. E., de Alkmim, M., & Godoy, C. (2002, April 12). Disinformation pulse: Reviewing the impacts of Disinformation in Brazil’s 2022 Elections. Instituto Igarapé .