Julian Barnes’ The Man in the Red Coat: Celebrity Culture in the Belle Epoque

In his latest novel, renowned British literary writer Julian Barnes creates a fascinating picture of gynaecologist and socialite Samuel Jean Pozzi (1846-1918). Barnes combines biography, art history and cultural analysis in a hybrid form of fact and fiction. In writing about the ‘Beautiful Era’ in France, an age and place of scandal, gossip and fake news, political corruption and violent language, Barnes mirrors today’s Britain. The message of the book is that there is much real life in literature and, vice versa, much fiction in reality.

Barnes' 17th novel and celebrity culture

Many scholars today relate celebrity culture to the contemporary entertainment industry and capitalism, to power constructions and expressions of individuality (Marshall, 2014). Celebrity culture developed in mediatised global public spheres, and since the 2000s, also in mobile media cultures. Celebrities are mediated and famed individuals engaged in public forms of discourse related to the attention economy. The celebrity figure as such, however, emerged already in the nineteenth century, with a romantic literary figure like Lord Byron as its ultimate representative.

Julian Barnes’ 17th novel revolves around Pozzi, a French doctor who was born in the provincial bourgeoisie and became a public figure and eminent surgeon in Paris. Pozzi transformed French gynaecology ‘from a mere subdivision of general medicine into a discipline in its own right’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 132). In 1890, he published a treatise on gynaecology of more than 1,100 pages with illustrations mostly based on his own drawings, which covered antiseptic procedures, anatomy, surgery and post-operative treatment. The treatise was translated in many languages and was soon recognised worldwide as a standard text.

Pozzi embodied different personas: he was a society doctor, a Don Juan, a Dreyfusard[1], the director of a Parisian hospital, a collector of books and art, a father of three, and a ‘generally cultivated conversationalist’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 6). He was unhappily married for thirty years but had had a partner in Emma Fischoff for decades. Pozzi was murdered in Paris in 1918 by one of his own patients, who shot him three times before committing suicide. The man, as Barnes suggests, was allegedly suffering from impotence, and although Pozzi had operated him, he had not been cured.

Medicine and art

The personal story of Pozzi’s life is interwoven with the story of two of his friends: Prince Edmond de Polignac and Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac. The three of them visited London in June 1885, and that is the setting in which the novel begins. They spent a few days of ‘intellectual and decorative shopping’; they went to the Handel Festival and were entertained for two days by famous author Henry James.

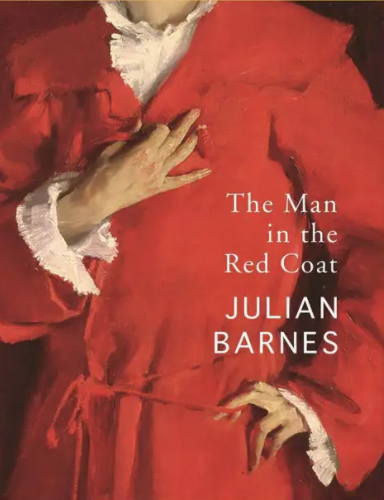

By putting the spotlight on three friends on a city trip, Barnes begins a detailed analysis of the activities, social norms and ‘structure of feeling’ (Williams, 1977) of the late 19th century. The author’s interest in the public figure of Pozzi started when he saw a portrait of the man in 2015 in the National Portrait Gallery in London. The painting was made by John Singer Sargent and it presents Pozzi elegantly and theatrically in a long red coat. The painted figure is, as Barnes (2019) writes, ‘virile, yet slender’, as well as handsome and bearded, while ‘gazing confidently over the left shoulder’ (p. 3). The eyes of the viewer are attracted to the hands of Pozzi, whose ‘fingers are the most expressive part of the portrait’ (ibid.).

Barnes conjures up a glittering and scandalous society full of writers, artists, duellists, snobs and dandies.

Barnes narrates the story of three friends, and also the story of their paintings by famous artists: Pozzi's portraits painted by Bostonian painter Sargent (in 1881) and by Léon Bonnat (1910), Montesquiou's portraits by Giovanni Boldini (in 1897) and James McNeill Whistler (1891-2) and de Polignac's picture included in a group portrait by James Tissot (1868). Public figures in the ninteenth century often appear in paintings, and their fame is established through the creation of artworks. Art indeed ‘outlasts individual whim, family pride, society’s orthodoxy’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 2).

But portrait photography was also an important up-and-coming genre in the last decades of the century, as is indicated by the many pictures that are printed in the margin of the text – most of them from the series of Félix Potin. Retailer Potin offered celebrity photographs ‘the size and shape of a cigarette card’ to his customers. The pictures were wrapped around chocolate bars. Between 1898 and 1922 three series were produced resulting in the Collection Félix Potin: 510 Célébrités Contemporaines (Emery, 2012, p. 63). People could archive the photographs in special albums. Pozzi, as Barnes (2019) describes, featured in the second series in two different poses both exuding ‘dynamism and self-confidence’ (p. 90). Photographs of celebrities were thus used as promotional items. The people of fame were, like today, royals and sportsmen (Italian cyclist Momo or English swimmer Billington), politicians, actresses, writers and popes. Their pictures functioned like the selfies we share in our time, meant to communicate with specific (micro-)publics.

The edition of the novel, by Jonathan Cape, is outstanding, a collector’s item itself. Reproductions of the paintings in colour and the black and white Potin photographs have an impact on the reading of the text: images and words stimulate the imagination but also challenge ideas about the representation of eternal fame and power. The three men are celebrities in their time, but the paintings and photographs are celebrity and cult objects as well.

Gossip and fake news

Barnes conjures up a glittering and scandalous society full of writers, artists, duellists, snobs and dandies (Montesquiou, Oscar Wilde, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Jean Lorrain). The dandy was ‘an Anglo-French phenomenon, criss-crossing the Channel throughout the nineteenth century. … Class was essential: you could hardly be a middle-class, let alone working class, dandy in England. In France, you were allowed to be a dandy in artistic, bohemian circles’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 56). Pozzi was not a dandy, although as a society doctor he treated foreign royalty and famous actresses like Sarah Bernhardt. He had an unfaltering work ethic and worked for thirty-five years at the public hospital Lourcine-Pascal, serving as its director from 1883 onwards. He was committed to science and rationality and can be considered an innovator in women’s medicine.

Barnes explains that ‘the more he researched the period, the more unavoidable the parallels became’.

The Belle Epoque was a time of ‘wealth for the wealthy, of social power for the aristocracy, of uncontrolled and intricate snobbery, of headlong colonial ambition, of artistic patronage, and of duels whose scale of violence often reflected personal irascibility more than offended honour’ (p. 135). It was also ‘an age of neurotic, even hysterical national anxiety, filled with political instability, crises and scandals’ (p. 26). The press was ‘violent in its language; libel laws slack, fake news prevalent; and killing never far away’ (p. 28). There was blood-and-soil nativism, and nationwide eruption of anti-Semitism.

In a Guardian interview (26 October 2019), Barnes explains that ‘the more he researched the period, the more unavoidable the parallels became’. Interestingly, in his satirical novel England, England (1998) he already described an isolated England, a marketable entertainment park on an island full of English stereotypes. The Man in the Red Coat is a more subtle critique on English recent political developments, celebrating a man who was ‘rational, scientific progressive, international and constantly inquisitive’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 266) and, as such, different from today’s English political leaders in every respect.

Pozzi, in his time, was attacked in newspapers in an extremely unpleasant way. He was accused of being ‘not really French’ (he was of Italian descent), of not being Catholic (he was a Protestant turned atheist), of being a free-thinker and of examining ‘with his bare hands the naked private part of good French catholic wives and daughters’ (p. 215). Although Pozzi experienced slander and hate speech, his career continued and his fame expanded.

Fiction and reality

Apart from the fascinating biographical details and the observations on dandyism and celebrity processes, on duels and politics, on art and collecting, what makes this work of literature particularly intriguing, is that it constantly questions the mechanisms of writing fiction. On a first reading level, this is a biography of three public figures in a late nineteenth century aristocratic context; we read it as a documentary and focus on information on the lives, the personal stories and the anecdotical peculiarities. But the reader immediately becomes aware of the influence that the writer has on the story and on how we perceive it.

Already from the start, there are seven alternative openings to the novel: there are the French men arriving in London; there is the honeymoon of Oscar and Constance Wilde; there are a gun and a bullet – which will be fired in the final scene; there is an operation in Kentucky in which an ovarian cyst is removed; there is a man just married; there is the red coat better described as a dressing gown; and there is the observation that the man inside of the coat is not remembered at all, we only remember him because of the famous painting.

Finally, there is yet another beginning introducing the three shoppers in the summer of 1885 by name, as real historical figures. But one of them, Count de Montesquiou, a ‘society figure, dandy, aesthete, connoisseur, quick wit and arbiter of fashion’ (p. 9) has been portrayed in A Rébours, a novel by Karl-Joris Huymans, as the protagonist Duc Jean Floressas des Esseintes. The real count and the novel character are one, as is evidenced in the description of their pet: a live, gilded tortoise. The authenticity of this detail effectuates a meticulous play of fact and fiction, of documentary and imagination, of reportage and exploration. Barnes demonstrates that ‘anyone can do anything in fiction’ (p. 103).

Count de Montesquiou is not only linked with the literary character Des Esseintes, but also with Baron de Charlus in M. Proust’s A la Recherche. The historical figure is modelled in fiction, but, as Barnes suggests, it is also the other way around. ‘There are more uncertainties in non-fiction than in fiction’ (p. 239). Further, as Barnes writes: ‘part of the novelist’s job is to turn a slight, even false rumour into a glitteringly certain reality; and it’s often the case that the less you have, the easier it is to make something from it’ (p. 39). The climax of this play with fact and fiction comes when Pozzi is shot by one of his own patients. Barnes uses his surprise to deconstruct the narrative: ‘A Don Juan shot dead by a man who blamed him for not curing his impotence: what sort of a morality tale is that? In fiction, it would seem cutely smug. Non-fiction is where we have to allow things to happen – because they did – which are glib and implausible and moralistic’ (p. 258).

What is the fate of the celebrity figure? Montesquiou made a success of being a dandy, of being talked about, even if he was not such a talented writer, and he ended up being a prominent literary character in two canonical novels. Pozzi, the ‘most eminent surgeon in France’ as the New York Herald Tribune described him, was forgotten, but reappears in this novel by one of the most notorious British writers. But Pozzi in The Man in the Red Coat does not turn into a literary character; rather, he is conceived as a real-life figure. ‘I would put him forward’, Barnes concludes, ‘as a kind of hero’.

References

Julian Barnes (2019), The Man in the Red Coat, London: Jonathan Cape.

Julian Barnes (1998), England, England, London: Vintage Books.

Elizabeth Emery (2012), Photojournalism and the Origins of the French Writer House Museum (1881-1914), Privacy, Publicity, and Personality, London & New York: Routledge.

P. David Marshall (2014), Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Williams, Raymond (1977), Marxism and Literature, Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

Notes

[1] Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of providing military secrets to the Germans. His trial and imprisonment caused a major political crisis in France.