Online gravedigging, identity and privacy

“I hate popular culture and pop music so much, but I don’t enjoy fine art and classical music either”. This is a sentence that I wrote 13 years ago in a Sina blog post. Blogging culture, born in the early Web 2.0 era, popularized individual online publishing. However, once challenged by social networking sites and later the advent of mobile internet, many blog sites in China became a kind of online Chernobyl, deserted by both the platform owners and users.

Unfortunately, I have no time to reflect on these fast-developing digital technologies as I feel so embarrassed by those old blog posts. The persistence of digital culture collapses timeframes and confronts me with my adolescent sentiments. The replicability of digital culture implies that every internet user can restore the visibility of my digital past, embarrassing me in front of more people in the here-and-now.

To revive a long abandoned post online is called “gravedigging”. If someone now reposts my “popular culture hate speech”, he or she is digging my digital grave. This article analyzes gravedigging as a digital practice, and illustrates its roles in online shaming and celebrity image management activities. Through two examples of online gravedigging, the article also discusses its implications for identity and privacy in a digital world.

The origin and development of online gravedigging

Gravedigging as a digital practice originates in online forums and BBS culture. Posts in many forums are often displayed according to the latest activities performed on them, such as likes or replies. Such a design encourages users to contribute more content and to do this more frequently. However, to reply or like a long-abandoned post grants a new round of visibility to the old stuff, helping the old post land in the top rank or the first page of a forum. For some forums where timeliness is of high relevance, the flood of old posts makes it difficult for users to navigate through useful information as it violates the synchronicity expectation that users have in online interactions.

Therefore, gravedigging, especially malicious large-scale gravedigging, is often forbidden by online community rules. We can argue that the reaction towards gravedigging is born out of online forum users’ bottom-up understanding of and engagement with platform popularity metrics.

The practice of “digging up” the "dead" or the old on the internet is then generalized to more contexts. Once gravedigging is applied to personal profiles on social networking platforms, this practice bears the connotation of revealing or disclosing damaging information about someone.

Doxing is a child of the anonymous internet

When we meet new “friends” online or offline, doing a background check on others’ social media profile is no longer a secret to anyone although it can be considered a little snoopy. However, such background checking does not aim to reveal or publish someone's personal information. In the labor market, employers may adopt “social network site screening” to check whether the candidates meet the requirements of the position. This is a highly controversial practice as many candidates feel that by doing this employers cross the boundary between the public and the private. It makes the scope of “requirements” fuzzy and discrimination may creep in.

Another related digital practice is “doxing” (or doxxing). Doxing refers to cases where personal and ostensibly private information about an individual is shared publicly, including one's real-life name, phone number, address, and/or workplace. (Phillips, 2015, p. 78). In China’s digital world, the equivalent practice is “human flesh search”. The term refers to “mediated search processes whereby online participants collectively find demographic and geographic information about deviant individuals, often with the shared intention to expose, shame, and punish them to reinstate legal justice or public morality” (Cheong and Gong, 2010, p. 472). Gravedigging is also a mediated search; however, it does not necessarily aim at tracing the offline “flesh”, the corporal being. The following two cases illustrate what roles gravedigging can play in different scenarios of digital communication.

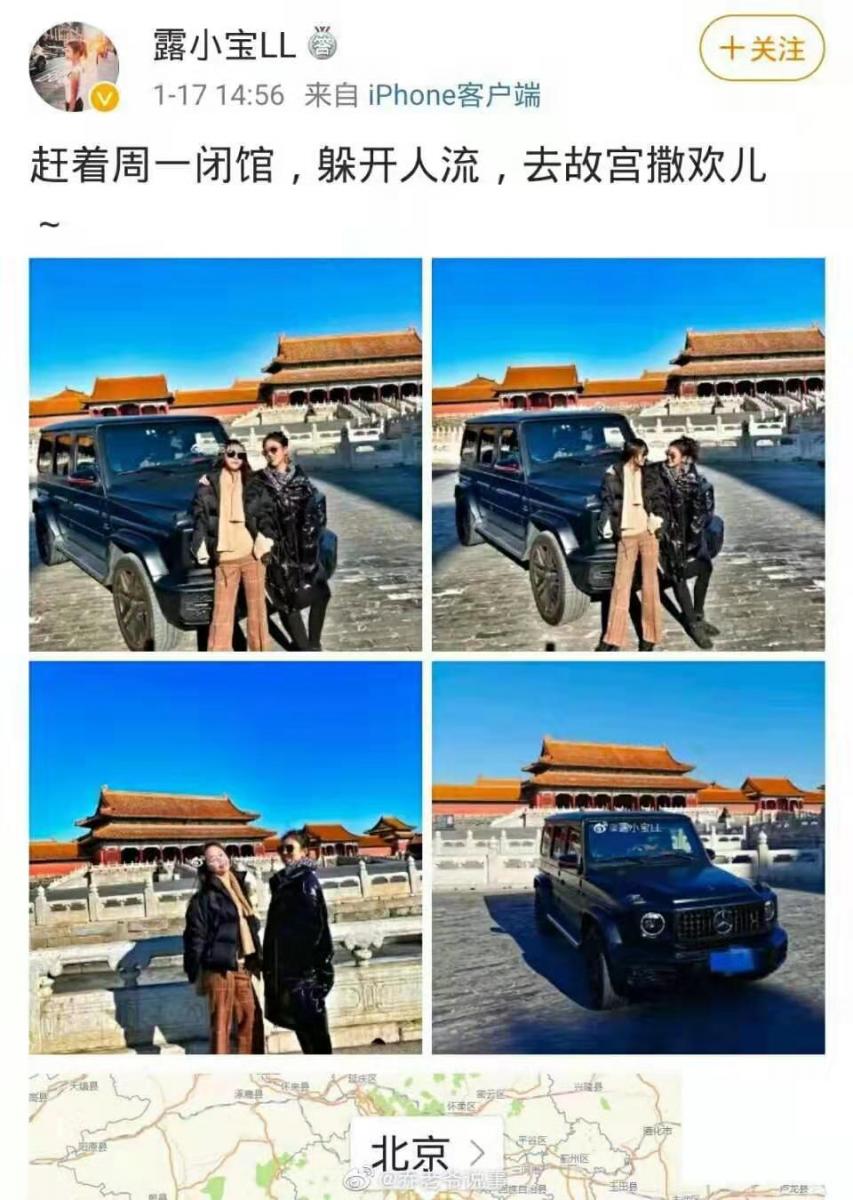

Driving an SUV in the Forbidden City

Gravedigging can play an important role in online shaming practices in China. A few days before the 2020 Chinese New Year, a scandal was exposed in which a woman drove her Mercedes-Benz G-Class SUV all the way into the Forbidden City on a Monday - the closing day. As the imperial palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the Forbidden City is one of the most treasured heritage sites of China. The former Palace Museum curator Shan Qixiang once revealed to the press that he even stopped former French president Hollande’s car when he visited the Forbidden City in 2013 because he believed that all visitors were equally responsible for protecting the physical integrity of such historical heritage.

However, the museum’s claim was contradicted by Lu Xiaobao's (screen name) own social media post in which she showed off her luxurious SUV parked in the central square of the Forbidden City. A public opinion backlash soon arose which not only criticized Lu, but also questioned whether taking a ride in the Forbidden City had been an all-time privilege.

Lu Xiaobao Drives SUV in The Forbidden City

Public outrage towards corruption and privilege has long fueled human flesh searches in China’s digital world. This was also no exception for Lu's case, whose former occupation and family relationships were quickly revealed by netizens’ collaborative searches. What makes a difference in this latest doxing case is the narrowing gap between the online and the offline. Netizens were not satisfied with knowing the target’s social background, they had also scrutinized all of the target’s social media profiles to dig up any damaging information she had posted. This "archaeological" search can be seen as gravedigging.

As an element of online shaming, gravedigging enhances shame’s expressive function.

Importantly, the old posts were selected as “historical evidence” informing the current incident to demonstrate that Lu is a person who violates social norms and loves lavish privilege. Such evidence was found, for instance, in a widely reposted screenshot from Lu's Weibo update in 2011, where she unashamedly admitted that she had crossed several red traffic lights.

As an element of online shaming, gravedigging enhances shame’s expressive function. The misbehaviors need to be exposed to the public so as to mobilize popular criticism and deter people from reiterating such censored forms of behavior. If the scarlet letter A expresses the crime of adultery symbolically, digital gravedigging broadcasts the sex tape: it expresses the violation of social norms with nuances, richness, and triviality, which social media encourage us to document in our everyday life.

Implications for identity online and offline

The definition of doxing shows that this practice emphasizes the link between a target’s online presence to one’s offline identity. Shaming practices often follow after a target has been identified as involved in wrongdoings. Doxing is a child of the anonymous internet, where the assumption that we can create an (online) identity that is not necessarily coherent with our offline one prevailed in cyberspace. However, in the process of policing the target’s misbehaviors online, the offline person is affected as well. This is not only because their offline identity is bound with institutional control and social relations, thus being bearer of legal or moral liability. Also importantly, in the early years of the internet, we simply found more information about a target when we traced him or her offline.

Our online presence can be as informative as what our social security profiles show.

The ontological status of the online-offline division and a postmodern reading of fragmented identities deserve fuller discussion in future articles. For the sake of the current discussion on gravedigging, it should suffice to note that first-generation social media platforms such as Facebook, Myspace and Chinese Xiaonei.com encouraged users to establish a “real name” online profile and to extend their existing offline networks into digital space. Later, the mobile internet helped to diffuse computing as an infrastructure in our everyday experiences. As Farman (2013) puts it, we no longer assume that we need to abandon the actual body to enter into the virtual internet; we live in the digital world.

A consequence of living in the digital world is the development of our digital double. To proceed with essential daily activities such as transportation, banking and healthcare, we leave digital traces of our private information. Besides the minute traces buried in big data, we also voluntarily share personal information in social media updates. This means that our online presence can be as informative as what our social security profiles show. Consequently, identifying and exposing an individual to the public does not stop at pointing out one’s demographic and geographic information. All the visibility that the target has created voluntarily can be recontextualized and weaponized to police the target.

Allen’s blog post

The second gravedigging case examined here is all about celebrity image management. The Chinese actor Allen recently received much media attention because of the TV show Under the Power, in which he stars. Having more than 15 million followers on Weibo, he has consistently been at the top of several celebrity popularity charts in China since January 2020. Allen has gone viral.

A person's celebrity status is commodified and traded among several media-related sectors, including but not limited to the advertisement, TV, fashion, and music industries. The image of a celebrity is therefore an economic asset that is tightly controlled by a celebrity management team. Allen’s media representation features his fashionable appearance, acting talent, and diligent work.

For ordinary individuals, the right to control information about a past self and the right to be forgotten are challenged by gravedigging practices.

However, fans are not satisfied with this tiresome "talented-and-hardworking" storyline used to legitimize every case of accession to stardom. Allen is part of the generation of Chinese youth who grew up with social media. Active fans soon digged up his Sina blog posts from 2007. The then 17-year-old Allen was a high school student who documented his adolescent sentimental life in the form of an online diary. He aspired to leadership on the school basketball court and condemned the school's heavy workload. He got emotionally hurt when his girlfriend cheated on him. He liked dancing and did not forget to post mirror selfies while practicing his dance moves.

Cover Page of Selected Essays of Guochao

Whatever "diagnosis" we can reach for adolescence and whatever celebration we give to youthfulness, we can find them in Allen’s digital past, and this will not be forgotten by the internet. The fans did not stop gravedigging. They filed all of Allen’s old social media posts into an edited volume and titled it A Selection of Essays from Guochao. Guochao is Allen’s name on his identity documents. Although not formally published, the volume has become a must-read for Allen’s fan community, causing a crisis for his celebrity image management. No one addresses Allen by his stage name anymore although it was carefully chosen to meet his fashionable appearance. Memes made from his old selfies were used by fans to comment on his recent media presence.

The pleasure and intellectual efforts of fandom in this case deserve more discussion than what I can offer here. But what is relevant in our current exploration of digital gravedigging is that this practice can confront us with our past in an uninvited and unpredictable way. A person’s ascension to stardom is an extreme case, of course, but for ordinary individuals, the right to control the information about a past self and the right to be forgotten are challenged by gravedigging practices.

Implications for the temporal dimension of privacy

If we understand privacy as a person’s right to control the public information flow about oneself, Marwick and boyd (2014) explain that privacy practices on social media should be conceptualized as being "networked" instead of individualistic. This is because the norms governing the flow of personal information are contextualized. However, social media platforms can collapse different audiences such as school friends and family members. The central functionality of sharing also disperses some control of personal information into other users’ hands, for instance when one is tagged in pictures.

Keeping privacy in mind as a networked phenomenon, we should also consider the temporal dimension of privacy practices on social media platforms. Users’ willingness to share more recent information can differ from their willingness to share content from years ago. Older posts may become less relevant to users’ current lives and they may not be coherent with users’ current self-representation (Bauer, et al, 2013). Users regret posting certain content, for instance content in which strong sentiments are expressed (Wang, et al, 2011) like Allen’s account of a failed romantic love affair. In her cultural analysis of memory, Eichhorn suggests that “maturation is as much an accumulation of knowledge as it is an accumulation of forgetting” (2019, p. 22). However, social media can disrupt our relationship to the past and remove our own agency with respect to it.

Privacy practices on social media are networked, not individualistic.

Several platforms have institutionalized this “concern over the past” into their platform design. This can be widely seen in second-generation social media platforms featuring fast-paced updates. Private photo snaps on Snapchat become inaccessible after a user-specified window of time (1-10 seconds). The “My Story” feature can be viewed only within 24 hours from when it is posted. These designs enable personal control, to some extent, over the persistence of digital cultural materials. They also nudge the users to post more, and post more quickly.

WeChat and Weibo in China let users adjust the accessibility period of all the posts on one’s profile. The posts are visible for the owner, but become inaccessible to visitors after a user-specified time. If the awkward confrontation with one’s past and the issue of complex audiences stop users from posting and participating on these platforms, the designers use ephemerality as a solution to keep users active.

Gravedigging’s role in digital communication

Online vigilantes who shame the SUV driver have very different sentiments compared to those of the joyful fans who laugh at every old picture of Allen. These two cases demonstrate that gravedigging can function as an ingredient in different digital communication practices. In analyzing social interactions, Goffman’s dramaturgical metaphor makes a spatial distinction. To manage our impression we “perform” according to the communicative norms in "front regions"; in "back regions", the impressions fostered in our performance are put aside and we, the performers, are out of our characters, we relax, and we prepare. The spatial metaphor reappears in the conceptualization of privacy if we define privacy as boundary management in which certain personal information should be kept inaccessible or accessible with some degree of control. These two cases of gravedigging reveal that both identity management and privacy practices in the digital world also have a temporal dimension.

References

Bauer, L., Cranor, L. F., Komanduri, S., Mazurek, M. L., Reiter, M. K., Sleeper, M., & Ur, B. (2013, November). The post anachronism: The temporal dimension of Facebook privacy. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM workshop on Workshop on privacy in the electronic society (pp. 1-12).

Cheong, P. H., & Gong, J. (2010). Cyber vigilantism, transmedia collective intelligence, and civic participation. Chinese Journal of Communication, 3(4), 471-487.

Eichhorn, K. (2019). The end of forgetting: Growing up with social media. Cambrdige, MA; London: Harvard University Press.

Farman, J. (2013). Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York & London: Routledge.

Phillips, W. (2015). This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Wang, Y., Norcie, G., Komanduri, S., Acquisti, A., Leon, P. G., & Cranor, L. F. (2011). I regretted the minute I pressed share" a qualitative study of regrets on Facebook. In Proceedings of the seventh symposium on usable privacy and security (pp. 1-16).