China's National Day Blockbuster: My People, My Country

This article explains why 'My people, my country' - a Chinese movie promoting a patriotic zeal and dominant political agenda - is becoming a worldwide hype not only in China, but also in the Chinese diaspora. This huge popularity of a movie on Chinese national day is a new phenomenon. Why is that?

My People, My Country

1st October, 2019 was an ordinary day in Tilburg, with typical Dutch weather, windy and wet. Many Chinese students disappeared from the Tilburg University campus in the afternoon and showed up at Pieter Vreedeplein to watch “the movie”.

The 70th Anniversary of the People’s Republic of China was a festivity that lasted for a month. Like the jingle of Christmas bells and the countdown on New Year’s Eve, the festive atmosphere built up and peaked with the Tiananmen military parade as well as the premiere of the movie My People, My Country. While the country was sacralized by displaying the latest nuclear missile that can reach any American state within 30 minutes, people shed tears in the cinema, affected by shared cultural memories and patriotic sentiments.

The festive mood travelled beyond the national border without the help of any ballistic missiles. Digital technologies and digital industry do the job. My People, My Country was imported into the Dutch market by a Chinese diaspora internet company. The local immigrants and international students were informed by peers on social media that the movie would be premiered in synchrony with the Chinese market.

National Day Box Office

Speaking in marketing lingo, the movie industry profits from the box office success of blockbusters in the summer and holiday periods. In the Chinese context, the most important movie seasons are summer holiday, the Spring Festival and in recent years National Day. Holiday movies may have become a festivity ritual in modern entertainment culture. Netflix devotes part of its website to a “holiday” genre, and television channels display Christmas classics such as Love, Actually or Home Alone every year. The Chinese Spring Festival box office began to boom in 1997, when the comedy The Dream Factory by director Feng Xiaogang became a huge success.

Expectations for a new all-star movie at the 70th Anniversary are amped up by this National Day box office tradition.

The National Day movie is a new tradition. Although the birth of the country has been extolled in many mainstream movies, the National Day box office boom signifies a convergence between political publicity and a privatized entertainment market. The 60th Anniversary of PRC was celebrated by the movie The Founding of a Republic, a historical film narrating how the current state was built out of the political and military struggles between the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang Party after WWII.

The movie was successful not only because it was commissioned by the government (hence receiving a longer theatrical window), or by block booking and more slots at cinemas. Importantly, it was an all-star movie where the historical figures were played by A-list actors and actresses. The founding of the country is a familiar script to Chinese audiences; however, showcasing more than 100 celebrities within 140 minutes creates a visual and cultural impact of sorts. The contrast becomes even sharper when historical figures known only from serious textbooks get embodied by widely known and popular comedians on the silver screen.

The Founding of a Republic

The Founding of a Republic laid the foundations for all-star mainstream movies, and was followed by the Founding of an Army and Beginning of the Great Revival. While promoting the mainstream political agenda of the communist party, the stories drew audiences’ attention by featuring celebrities and teen idols. No wonder, then, that expectations for a new all-star movie for the 70th Anniversary were amped up by this National Day box office tradition.

The Ordinary People

Since the founding of the country was already the core theme of the 60th anniversary film, the scriptwriters and directors could not return to the by now thoroughly familiar story. The result is a thorough innovation of representation in My People, My Country, contextualizing ordinary people’s lives during historical moments in the history of the nation. Ordinary people as role models for socialist citizens is a token of public figures in China. Model workers, model soldiers, model communist cadres and champion athletes are publicized on mainstream media to promote and exemplify morality and morale in public life. However, once ordinary people becomes models, the publicity lifts their ordinariness to extraordinariness ─ a process of ascension. In contrast, the characters in My People, My Country signify a majority whose names remain unknown.

The Chinese Dream in the movie personifies, but not individualizes; celebrates, not celebritizes.

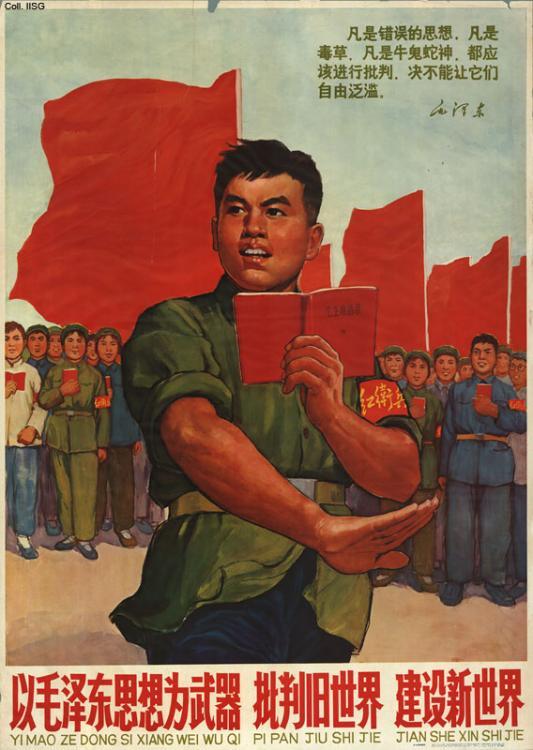

However, we may not equate these citiziens with the faceless masses in the political posters from the Cultural Revolution: a sea of revolutionaries clad in military uniform, brandishing the same little red book and standing in the same posture. My People, My Country attaches a human face to historical events. But the human face does not seperate the individual’s destiny from history; it does not turn them, for example, into the self-made men or women of the American Dream. In dealing with the relationship between the people and the country, the Chinese Dream in My People, My Country personifies, but does not individualize; it celebrates, but does not celebritize.

A Poster during the Cultural Revolution

My Country, My People Poster

Non-heroes and Laughter

The film is composed of seven stories referencing seven significant moments since the founding of the country. The first chapter titled The Eve depicts how engineer Lin Zhiyuan, overcoming technical difficulties, successfully installed the automatic flag-raising mechanism on Tiananmen Square at the eve of the founding ceremony of 1st October, 1949.

Fast-forwarding to 1960s, the second story Passing By is about a scientist who left his fiancée to do confidential research on the Chinese atomic bomb. While these two stories are imbued with a sense of heaviness derived from a highly politicized past, the third story The Champion lightens the mood by depicting how a local community in Shanghai enthusiastically follows the women’s volleyball final in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics Games. Following the timeline, Going Home tells the backstage story of how the 1997 Hong Kong Handover Ceremony was negotiated out of conflicts and prepared with commitments.

The Olympic theme is brought up again by Hello Beijing, in which a Beijing taxi driver gives his treasured Olympics Opening Ceremony ticket to a boy from Wenchuan. The boy’s father once participated in the construction of the national stadium, but died in the devastating Wenchuan earthquake less than three months before the opening ceremony.

The Guiding Star is the chapter that has sparked most controversy (see below). In the story, a pair of brothers from a poor minority background witness the landing of the spacecraft “Shenzhou 11” and are deeply inspired by it. The final story One For All is devoted to a female fighter aircraft pilot who makes difficult decisions balancing her personal life, her friendships and her military mission.

My people, My Country connects a political agenda with humorous non-heroes and audiences’ popular cultural memories.

Based on this very brief summary, My People and My Country appears to be a film that promotes a dominant political ideology in a direct and simplistic way. However, this does not do justice to the veritable hype that erupted after the trailer was released online, nor to the extent to which it triggers alternating tears and laughter among audiences viewing the movie in cinemas. There are many significant moments in a country’s collective memory. The seven stories focus on only three themes: political ceremony, military (space) technology and competitive sports. These are recurring chronotopes where collective national sentiments can be expressed. Building upon the three themes, the struggles of individuals and the country are unified.

Tragedies belong to heroes. The ordinary Chinese in My People, My Country bring smiles to their audiences. The engineer jumps up towards the sky to celebrate his contribution to the founding ceremony - an anachronistic gesture belonging not to his generation, but to the young audiences who share holiday pictures on social media. When watching the intense volleyball match, the protagonist boy needs to hold the TV antenna to enable the whole community to watch the game. As a result, he missed a rendez-vous with his girlfriend who emigrated to a foreign country on that night. This naughty kid on the house roof reminds us of Amélie’s childhood, and the innocent romance invokes audiences' nostalgic memories about their own school years. The Beijing Taxi driver was ticketed for a parking violation. When he ran after the police, audiences were brought back to the 1999 Spring Festival movie Sorry Baby, where the same actor Ge You performed exactly the same scene.

The pilot’s boyfriend received the most laughter. He is a frightened man living in the shadow of his heroic soldier-girlfriend. When he complained about being ignored by saying, ‘you fly airplanes in the sky every day, I…’ The latter half of the sentence was swallowed back. But audiences assume the following line to be ‘I shoot airplanes everyday’, a euphemism for masturbation in Chinese. People laugh out loudly not only for his flawed masculinity, but also for the unexpected sexual slang innuendo in an otherwise serious National Day movie. Hypocrisy never laughs; it wears a serous mask, Bakhtin told us. My people, My Country connects a political agenda with humorous non-heroes and audiences’ cultural memories. It suggests the state’s cultural power to manage political ambiguity.

A United Front

In China, a film with such cultural and political importance often tries to include a wide range of social characters, or in Gramsci’s words, to unite different power blocs. The first two stories suggest that the Chinese intelligentsia is an integral part of China’s political power. Audiences giggle at the nerdy engineer who repeated, ‘according to the experiment, there is still a possibility…’

In the next scene, they are touched by Beijing citizens who donated whatever metal they had at home to construct the flagpole in Tiananmen Square. However, the only useful material comes from a chemist of Tsinghua University who brought the last metal specimen from the university lab. When the flag-raising experiment was running out of time with its musical preparations, the trumpeter plays the national anthem live for the engineer. The trumpeter was a university student of the Foreign Language School at Peking University. Metaphorically, the story implies that without experts, engineers and human intellectuals, the Chinese national flag could not be raised.

Metaphorically, the story implies that without experts, engineers and humanity intellectuals, the Chinese national flag could not be raised.

A united front also makes sure that ethnic minorities are included. My People, My Country indeed shows serious improvement in representational work. This is the first time that ethnic minority characters are not tokenized, bearing the orientalist burden and functioning as a decoration prop in major political events - as was the case in previous mainstream movies. The Guiding Star tells the story of two Mongolian teenagers. They do not wear the traditional Mongolian gowns while dancing and singing ‘I walk from the grassland to Tiananmen Square, I raise my golden grail to sing the hymn’, as Mongolians did in a classic image from the epic dance show The East is Red, dedicated to the 15th anniversary of the country. The two brothers in My people, My Country are school dropouts, sent to juvenile detention because of stealing. They represent the impoverished youth population in China, a societal issue that the government needs to solve.

Mongolian ethnic in The East Is Red

The two brothers in My People, My Country

Our two Mongolian Jean Valjeans experienced redemption through a communist bishop’s pastoring.

When the two boys return to their hometown from the detention center, they meet their mentor: a local communist cadre who has been carrying out poverty reduction projects in that area. In spite of the care and help from the mentor, the two boys steal a large sum of money from the mentor’s house and get caught by the police again. Surprisingly, the mentor forgives the young boys. Our two Mongolian Jean Valjeans experience redemption through a communist bishop’s pastoring. The story makes an intertextual reference to Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Such reference to a Western classic implies the director’s effort to contextualize Chinese people’s achievements against universal human values rather than within the binary coding of liberal democracy and communism. This also explains why the Big Others ─ vicious America, historically guilty Japan and rival sibling Taiwan ─ which were often depicted in previous mainstream movies to invoke patriotism, are absent from this movie.

Of course, Chinese young people are not all miserable. According to ancient Mongolian myths, the impoverished land will become prosperous once people witness a shooting star at daytime. And yes, the two brothers indeed see a shooting star at daytime falling on the vast grassland: the returning spacecraft carrying the Chinese astronauts. It heralds the largest controversy caused by the movie. Audiences critically noted that, in real life, no civilians could get close to the spacecraft, as its landing site was a military zone. Apparently, the director forewent realism for the sake of poetic imagination. On the one hand, the metaphor implies that old beliefs cannot save the land from poverty; only science and technology can. On the other hand, the ancient prophets may not be wrong. They have predicted the country’s revival, and this becomes a reality under the leadership of the communist party. Through this metaphor, the state-launched modernization project is romanticized and the state is legitimized.

It may fail to erase a falsely assumed conflictual connection between feminism and femininity

Women holding up half of China’s sky (a traditional Chinese metaphor), also play key roles in the movie. The (then) most advanced fighter aircraft J-10 are flown by women, suggesting that they not only hold up the sky - they also expertly navigate through it. The protagonist female pilot was a tomboy at school, happy to fight the boys in her class. She then broke up with her boyfriend due to the demanding work in the army. In the end, she chose to be a backup aviator in an important mission and facilitated her comrade-friend to fulfil the task - a recurring theme of female friendship in many women’s genres.

Female fighter aircraft pilots

Some commentators have suggested that this story is the only chapter that does not betray a male gaze. However, this fails to erase the wrongly assumed and conflictual connection between feminism and femininity, a conundrum starting with the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mao’s era. Women have to do a man’s job and behave like a man to become important forces of socialist construction. The alternative is to re-align women with traditional femininity. Of course, we can understand that the theme of military power, where women are not in the majority, may have limited the storyteller’s room to manoeuver around women’s lives with regard to issues of femininity and marriage.

Re-semiotizing China

The movie’s title is also the name of its theme song. My People, My Country as a song was originally published in 1985 and was performed by the renowned singer Li Guyi. The word “popularity” deserves some attention here. It is popular, as mainstream media often play it and students learn the song from music textbooks, performing it in school chorus practice. Indeed, the song is widely known in China. However, it does not belong to popular culture if we associate “popularity” with the commercialized cultural industry or young people’s individual desires and identifications with media content. They have their underground rock-'n’-roll, ethnic hip-hop or pop idols to follow. My People, My Country as a mainstream patriotic song may not appear on their musical hit lists.

My people, My Country still subscribes to a grand narrative of development, but it has re-semiotized the country by filling the emptiness of grandiosity with personal stories, humor and colossal cultural resources.

The ambiguity of popularity brings us to the “secret ingredient” or “X-factor” contributing to the hype provoked by the movie's trailer. This time, the theme song is re-interpreted by China’s most prominent pop singer Faye Wong. Growing up in Beijing and making her media debut in Hong Kong in 1989, Faye is regarded as the Diva of the pop music industry in Greater China. Her celebrity image is marked by a sense of "coolness" and individualism. She is the pop idol of China’s millennium generation and her voice speaks to the kinds of multiple audiences (including audiences in Hong Kong and Taiwan) that a united front of China strives to include. As soon as the song was released, a week before the movie’s premiere, audiences commented online that in the old version, one can only sense the country’s greatness, whereas this time Faye's voice was said to describe the “happy people” in this country.

Personified perspective: national stadium seen through the eyes of a taxi driver

Mainstream political representations in China are used to depict grandiosity. High-rising skyscrapers index modernity, the solemn Forbidden City bespeaks centuries-old traditions. Technological developments are represented by the mushroom cloud of atomic power and the data visualizations of the digital industry. Human faces, especially those of ordinary people, are absent from the panorama of the country’s achievements. My People, My Country still subscribes to a grand narrative of development, but it has re-semiotized the country by filling the emptiness of grandiosity with personal stories, humor and colossal cultural resources. As the song’s lyrics suggest ‘Me and My Country' signifies an unbreakable unity between individuals and country, and the seven stories enable all audiences, in their myriad diversities, to recognize themselves in the 70-year history of the country. Ideological unity and collectivity are thus achieved by conveying that “I am the country”, and by pouring this message into contemporary cultural material adjusted to old and new generations alike. The mass response to the song and the movie shows that this act of cultural engineering has worked quite well.