How Fleabag uses the fourth wall to create intimacy

In the acclaimed television series Fleabag, the audience is Fleabag’s best friend. By constantly making eye contact with the camera and talking directly to the viewer, the lead character, named Fleabag, is almost continuously breaking the fourth wall. This article will analyze what breaking the fourth wall means for the relationship that Fleabag develops with the viewer: how does Fleabag use this device to create and maintain an intimate relationship with viewers, what does this intimacy mean for the audience, and how can narrativity be used to contribute to that intimacy?

The fourth wall

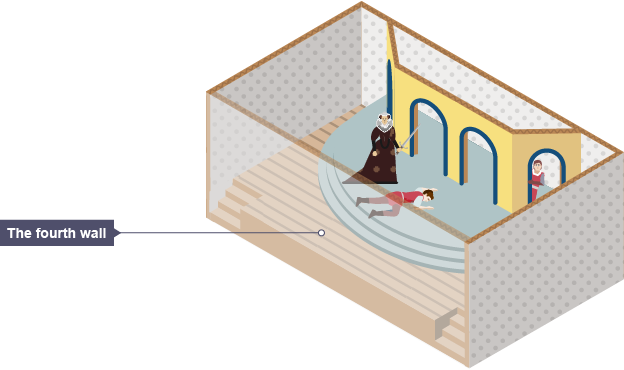

The concept of the fourth wall comes from the theatre, where the three walls of the stage are complemented by a fourth, imaginary wall placed between the actors and audience (Lionheart Theatre, 2016). This fourth wall serves as a conceptual barrier that the audience can see through, while the actors cannot, or rather pretend to not be able to. This separation - this wall - between actors and audience, concerns the relationship between the two and implies that "the characters are unaware of the fact that they’re fictional characters in a work, the audience observing them, and whatever medium conventions occur in between the two" (Tvtropes, 2020). In other words, in order to keep that fourth wall up, actors must pretend as if the audience is not there (Lionheart Theatre, 2016).

The fourth wall in theatre.

This unacknowledgement of the audience is a staple for most television series (or really, any work of fiction). Most of the time, we are watching the characters but the characters are not aware of their audience and do not interact directly with the viewers. Breaking that fourth wall, therefore, means the opposite of unacknowledgement: a character "acknowledges their fictionality, by either indirectly or directly addressing the audience" (Tvtropes, 2020).

We can use examples from the theatre to make this more specific. Imagine visiting the theatre to see a "serious" play: the actors are immersed in their own story and do not talk to the audience. You, as a viewer, are not part of the fictional story. Now think of going to the theatre for a night of comedy: the comedian will not ignore the audience, but instead talk directly to the audience. The fourth wall - the separation - is no longer there, because the audience has lost its invisibility.

In television series, this "break" can be seen in the characters being aware of the camera and acknowledging that there is an audience that they can talk to. Examples of this are seen in the sitcom The Office, where characters make eye contact with the camera, or in reality television, where the people starring talk directly to the camera during confessionals. So, in order to break that fourth wall, actors need to show awareness of the audience and address them directly.

Fleabag

Fleabag is a British comedy-drama television series that aired from 2016 to 2019 on BBC. It follows a sarcastic, unfiltered and dry-witted thirty-three-year-old woman named Fleabag. We follow her living her life in London as she tries to deal with family, love and the loss of her best friend Boo (Wikipedia, 2020). The show was created by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who also plays the leading part of Fleabag. What makes the show so interesting is that Fleabag is very aware of the audience watching, and she almost continuously breaks that fourth wall by looking into the camera and making eye contact, pulling weird faces only for the viewer to see, and talking directly to the viewer which allows her to "confess" her very personal thoughts only to them.

As we can see in the video above, Fleabag is the only character who has this relationship with the viewer, and the other characters do not seem to hear the things that she tells us. Not only does this lead to the development of a very intimate and personal relationship with the audience, it also first and foremost shows an awareness of the audience or, to go even further, it shows a preference for the audience. Fleabag consciously decides to share her raw internal monologues and her sarcastic (or inappropriate) commentary with us, instead of with the other characters. The audience is at an advantage here: we know Fleabag’s genuine opinions about her life and relationships better than her family and (boy)friends do.

With help from specific scenes and the Fleabag "scriptures", this article will explore how Fleabag uses this device, what kind of intimacy the show creates, and the important connection between narrativity and intimacy.

Who exactly is "you"?

Fleabag presents herself as being unashamed of her thoughts, talks to you as her best friend in an informal way (in fact, with lots of swearing) and she is direct and unfiltered. By referring to us as "you", she uses an impersonal second-person address, both implying awareness of the camera as well as objectivization. With this latter term, we mean that the camera functions as one, general substitute for every individual, instead of Fleabag interacting with every unique viewer individually. According to Wong (2019), "Fleabag’s use of second-person address is generalized and impersonal in the sense that who we are as specific individuals seems to matter less than the fact that we are present and observing, yet we intuit that she is speaking directly to us (the viewers).".

Using "you" for the audience, in combination with the fact that Fleabag never reveals her actual name, also leaves a lot of room for interpretation and speculation. On online forums such as Reddit, Fleabag fans discuss the role of "you". Some think the audience is Boo (Fleabag's deceased best friend), especially because Fleabag does not acknowledge the camera during flashbacks with Boo. Yet, others disagree because thinking of Boo always makes Fleabag sad, while the interactions she has with "us" are mostly funny or happy ones. Others yet suggest that "you" stands for Fleabag herself. This is supported by the fact that the other characters also always call her "you" instead of using a name such as Fleabag (Wong, 2019). Besides that, given that "we" have been in her mind since the very beginning, it actually seems plausible for Fleabag to be talking to herself. Either way, whether "you" is meant for Boo, Fleabag, this general "us", or every viewer individually, the connection that Fleabag has with the audience results in the audience feeling compelled to follow her life.

Why Fleabag breaks the fourth wall

Breaking the fourth wall can be done for many reasons. For example, it can serve to connect with the audience and create more audience engagement and participation, or to trigger laughs when used as a comedic device (Brown, 2013). For the latter, you can think of lines from musicals like "we need to stop singing or we’ll never get through this scene" (Lionheart Theatre, 2016). Such uses strengthen the relationship between actors and audience.

However, when not executed carefully, breaking the fourth wall can also create more distance. If the break does not feel intentional, it can lead to a disruption of the story, a sign of amateurism, or frustration on the audience’s end. If done too subtly or too heavy, it disrupts the pace of the story, which leads to viewers being "out" of it instead of being fully immersed (Rivera, 2014). Therefore, destroying or keeping the fourth wall intact, should always be done in a conscious and precise manner.

If breaking the fourth wall does not feel intentional, it can lead to a disruption of the story, a sign of amateurism, or frustration on the audience’s end.

Unlike The Office, where breaking the fourth wall was needed to create a realistic (fictional) documentary parody of modern American office life, Fleabag can keep the fourth wall intact without losing much of its sense of realism and lifelike representation. What both shows share is the use of the fourth wall as a comedic device or a way to break the awkwardness of scenes. Fleabag is a show filled with intense and awkward moments that leave room for vicarious shame, and by talking to us, awkward silences get filled and embarrassment gets (subjectively) justified by Fleabag’s commentary.

We can see this in the scene below, where Fleabag has a family dinner filled with tension, awkward moments, and above all, people who seem to be forced to have fun together. By breaking the scenes and turning to the camera, Fleabag manages to make the dinner feel less long and unbearable than it supposedly was. Through the use of irony and sarcasm, Fleabag deflects painful feelings. Humor is her coping mechanism.

Still, for Fleabag, this is more than just sharing funny commentary: Fleabag seems to need the audience, it's like she cannot manage without us. Show creator and lead actress Phoebe Waller-Bridge explained why breaking that fourth wall is so important for Fleabag's character: "Fleabag was always performing for the camera to distract both herself and the audience from her misery. (...) Her drive was to entertain you, so she could never allow herself to be a victim for fear of boring you" (Wright, 2019). Not only does this emphasize that Fleabag needs us to distract herself, but it also tells us a lot about the kind of person she is. She wants (or feels the need) to charm "us", and uses "us" to keep her own life interesting.

As already mentioned, breaking the fourth wall can lead to a stronger connection with the audience and more audience engagement. By dragging the viewer into her life, Fleabag is turning the viewer into a character (Reddit, 2019a). Waller-Bridge refers to the device as "her secret camera friend" (VanArendonk, 2019). It is Fleabag’s way of confessing her genuine thoughts to help you understand her better. The audience needs those direct address moments in order to fill in the gaps and this prevents Fleabag from being a very closed-off character. The "camera friend" is "secret" because, unlike in reality television where every character is aware of the camera, no other Fleabag character knows about "us". It is a perfect way to communicate vital information, engage the viewer, build trust and be funny at the same time.

The scene below shows both how to engage the viewer by way of quick conversations and witty comebacks, as well as using funny elements to "entertain" the audience. Especially in the beginning, Fleabag has some direct interactions with the audience.

With mock-documentaries, there is a contract set up between producer and audience that "requires the audience to watch as if at a documentary presentation, but in the full knowledge of an actual fictional status" (Springer, 2005). In other words, the audience gets to enjoy the truth as it is told, while also knowing that it is fictional - think of The Office, for example. This idea of the "knowing" audience can be applied to Fleabag because the whole series is seen through the protagonist's eyes, and every time Fleabag turns to the camera she confesses "her truth". This confessional holds an expectation of truth about Fleabag and shows how identity and truth are connected. "Storytelling is a mechanism by which one constructs one’s truth and identity within the text of the film narrative" (Waites, 2015). Fleabag is the story she tells us, and since truth depends on who is telling it, this demands an active and attentive audience that reflects on this subjective truth.

Lastly, we can say that the fourth wall is supposed to form a separation between us and Fleabag, but what actually happens is that Fleabag forms a separation between herself and her family every single time she talks to us. This is reinforced by the use of shallow focus: when Fleabag turns to us, the people in the background get blurry. Turning her face to the camera means turning away from her own family or friends. Therefore, the fourth wall creates a a new separation.

Intimacy between Fleabag and the viewer

The two most widely used techniques for creating an intimate relationship between Fleabag and the audience are eye contact and direct addresses. The way Fleabag looks and talks into the camera is shameless and fearless. By looking at and talking directly to the viewer, she takes away the invisibility of the audience and shows awareness of "us". During a counselling session scene (see video below, 2:57 minutes), Fleabag even makes the powerful move of literally mentioning "us". When asked whether she has any friends, she responds by saying yes, winking to the camera, and saying "they are always there". "In just a few seconds, it becomes clear that Waller-Bridge’s character is aware in-narrative of the presence she’s referencing [and] conceptualizes it as a collective rather than an individual" (Ettenhofer, 2019). It also seems to indicate that Fleabag prefers to talk to us, rather than the other people in her life.

Because "we" are part of Fleabag’s life, the intimacy also creates a certain discomfort, especially during awkward or tense scenes where you would rather look away. But, while the moment itself might be painful or embarrassing for Fleabag, she tries to make it interesting for the viewer through providing commentary on her life. Fleabag "effectively removes herself from the intensity of those who can talk and clap back to her in actual life. She shares her core with an audience that she cannot see, hear, or touch" (Killian, 2019).

This core consists of the most random, rather impolite, personal, and sensitive topics. This vulnerable position that Fleabag puts herself in creates trust and holds the expectation that "we" are her confidantes. This does not only require braveness from Fleabag’s side, it also requires something from the audience: in order to create and maintain this intimacy, "we" need to be open to receiving all this information and accepting being a character to her. Being part of her life also means being part of the not-so-great or awkward moments.

The kind of intimacy that is fostered here, might be seen as one-way intimacy partly because it starts out one-sided with Fleabag initiating an intimate relationship, but it can turn into a two-sided relationship if the viewer shows willingness. The intimacy feels one-sided also partly because Fleabag acknowledges the audience without ever truly seeing every individual viewer. It is a kind of intimacy where Fleabag needs the audience, and therefore we are highly visible to her, whereas the audience has a choice to either reciprocate the intimacy by bonding with the character or leave it one-sided. At least, that is the impression we get until the end of season 1, where the viewer brutally becomes aware of how Fleabag did not disclose everything about herself.

Boo scene.

In this final episode, Fleabag reveals a secret about herself that might change how the viewer perceives her. Whereas "we" used to be her best friends and confidantes, Fleabag now tries to push the camera away and refuses to look at us or say a word (see scriptures above). Fleabag is ashamed of her secret and not sure about whether we still like her. "She doesn’t want us there anymore, her guard is down" (Waller-Bridge, 2019b). All the confessional moments have led to the viewer being part of her life, but this time, Fleabag has taken the confessional too far. Some fans argue that "we" used to be Fleabag’s coping mechanism (Reddit, 2019b), but now that the secret is out, she can no longer "use" us in this way. She returns to herself and makes this a one-sided relationship again, only this time the desire for intimacy is on "our" side.

Distance and intimacy in Fleabag

Moving from the theatre - Fleabag began as a theatre play - to the screen, we see some changes in narrative and intimacy. On stage, Fleabag was alone without any other stage action to turn to, which led to constant contact with the audience. On screen, Fleabag can turn to and away from us whenever she wants. "Whenever Fleabag addresses the camera mid-narrative, the flow of narrative does not pause: the frame does not freeze on screen when she responds to another character while looking at the camera or makes a quick snarky comment" (Wong, 2019). In other words, breaking the fourth wall does not mean a disruption of the flow of the narrative or scene. Fleabag’s commentary is closely interwoven with the narrative, and produces a sense of immediacy: the viewer gets immediate responses from Fleabag, rather than post-hoc reflections. This means that the distance between narrator and narrated is minimised, which leads to more intimacy (Wong, 2019).

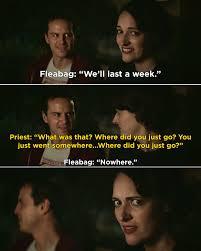

But never underestimate Fleabag. Although she is good at building up intimacy and showing that she cares about "us", she is also good at quickly destroying this delicate intimacy and showing that she is ashamed of us. In the second season, we meet the "hot" priest who, after getting to know Fleabag better, starts to see right through her. He notices how she looks away - at "us" - and asks her about it, to which Fleabag responds with "it’s nothing". She feels ashamed and embarrassed about being "caught" interacting with "us".

The priest notices for the first time.

This scene shows us a couple of things. First of all, the priest is the only one who "catches" Fleabag breaking the fourth wall, which fans have interpreted as him being the only one who actually pays attention to her. Some fans attribute this to the priest having supernatural, "holy" connections with people, while others say that the priest understands her because the viewer-Fleabag relationship can be compared to the priest-God relationship. Fleabag has an intimate connection with the audience, and the Priest has this connection with God. They both have their "imaginary" friends (Reddit, 2019a. Reddit, 2019c).

As the priest keeps noticing that Fleabag turns away, he wants to understand what is happening. So, in the scene below, he - as the first and only character besides Fleabag - looks us straight in the eye. This scene shows both intimacy and distance. As a viewer, you are shocked: this "bubble" that you were living in with Fleabag is abruptly burst by the priest. This is a testament to how intimate and secret your relationship with Fleabag was all this time, and how the viewer now also needs to reserve this extra space to let the priest in.

There is so much to see here: Fleabag is both embarrassed and shocked that the priest is getting so close. At the end, she even says that she does not want the priest to get to know her. We see this internal battle in Fleabag, where she is confused about what to think of the priest, her feelings towards "us", and how those two worlds work together. Fleabag wants to keep "us" a secret and is unsure about what this says about herself. She is creating confusion on the viewer’s side, where she both wants us and is ashamed of us. In this scene, Fleabag is creating both distance and intimacy with the viewer at the same time.

Fleabag’s scriptures: Fleabag is her story

Lastly, I want to use the Fleabag scriptures (Waller-Bridge, 2019a) to discuss how narrativity can contribute to the creation of intimacy. Strawson speaks of the Psychological Narrativity Thesis: "a straightforwardly empirical, descriptive thesis about the way ordinary human beings actually experience their lives" (Strawson, 2004). According to this theory, we live our life like a story. This tendency to see our lives as narratives, as a collection of stories, is in our nature. "A man is always a teller of stories, he lives surrounded by his own stories and those of other people, he sees everything that happens to him in terms of these stories. (...) ‘Each of us constructs and lives a ‘narrative’ (...) this narrative is us, our identities" (Strawson, 2004).

This Psychological Narrativity Thesis applies to Fleabag. By constantly providing commentary on her life, she does not only put it in a story, but she actively feels the need to narrate her life and become her story. Of course, the character Fleabag is not the only agent here. The creator of the show, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, also plays a massive role in creating and maintaining the relationship between character and audience. It is because of Waller-Bridge and her decision as an author to choose a way of narrating that breaks the fourth wall, that the audience experiences both intimacy and distance. The show is fast, abrupt, very dynamic, has flashbacks and jump cuts, and yet it feels sort of chronological. The scenes can really be as chaotic and weird as Fleabag’s mind is, but because Waller-Bridge uses the character Fleabag to give us - the viewers - additional background information through Fleabag’s opinions and thoughts, the viewer gets the right tools and information to put Fleabag’s life into a coherent story.

"Each of us constructs and lives a ‘narrative’ (...) this narrative is us, our identities."

This "right" information can be provided by Fleabag in many ways: (1) revealing facts or opinions about the characters, (2) explaining reactions, (3) narrating what is happening, or (4) extracting more information about the past. I will quickly explain all four of them.

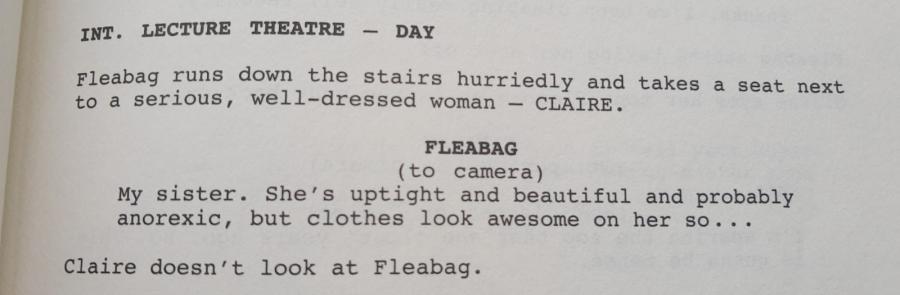

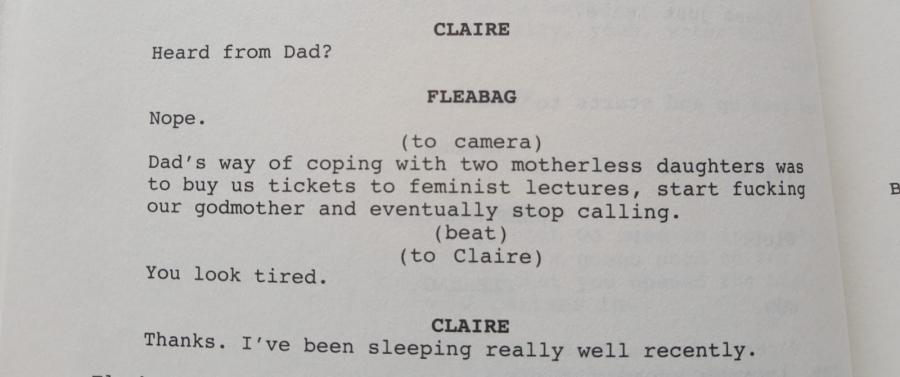

(1) In the first episode, Fleabag introduces us to her family in a frank and direct way. She describes her sister as "uptight, beautiful, and probably anorexic", while her father gets introduced as "Dad’s way of coping with two motherless daughters was to buy us tickets to feminist lectures, start fucking our godmother and eventually stop calling." This does not only give the viewer an idea of what kind of person Fleabag’s father is (according to Fleabag), it also makes it clear that Fleabag’s mom passed away and her godmother is now her stepmother. Character information like this helps the viewer create an overview of Fleabag’s family and understand where Fleabag is coming from (which is an important foundation for an intimate relationship).

The introduction of Claire.

The introduction of Fleabag's dad.

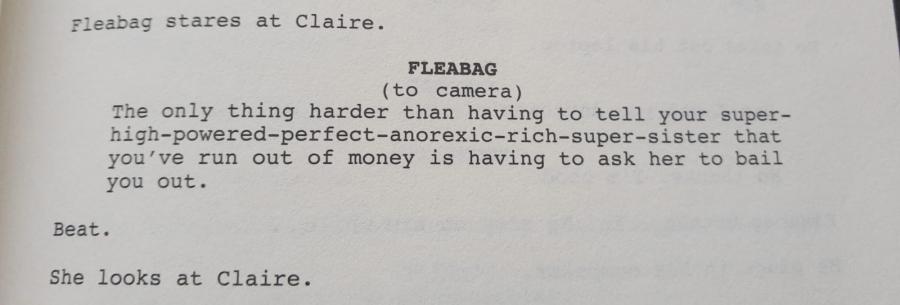

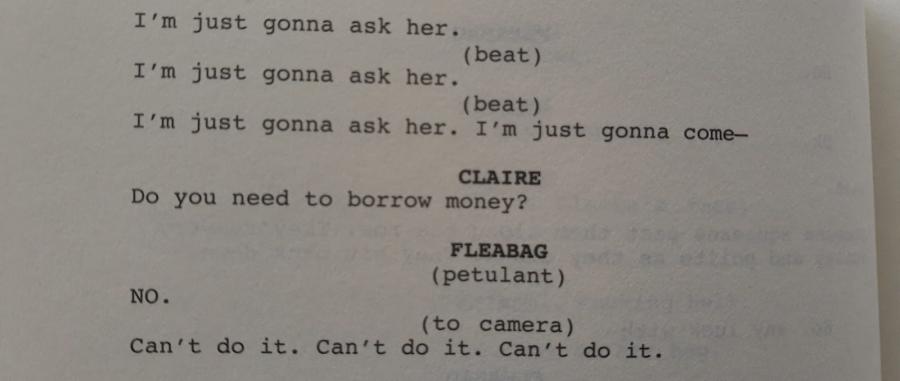

(2) Whether Fleabag comments on her or others' reactions, it always allows the viewer to understand where underlying feelings or decisions are coming from. For instance, in season 1, Fleabag is struggling financially, but turns down her sister’s offer to lend her some money. Because of Fleabag’s narration, we understand her thought process: Fleabag finds it difficult to ask her "powered-perfect-rich-super-sister" to ask for help because it makes her feel like the failed sister.

Fleabag turns down Claire's money.

To the camera, Fleabag says "I'm just gonna ask her", while to her sister, she answers: "NO".

Fleabag turns down Claire's money.

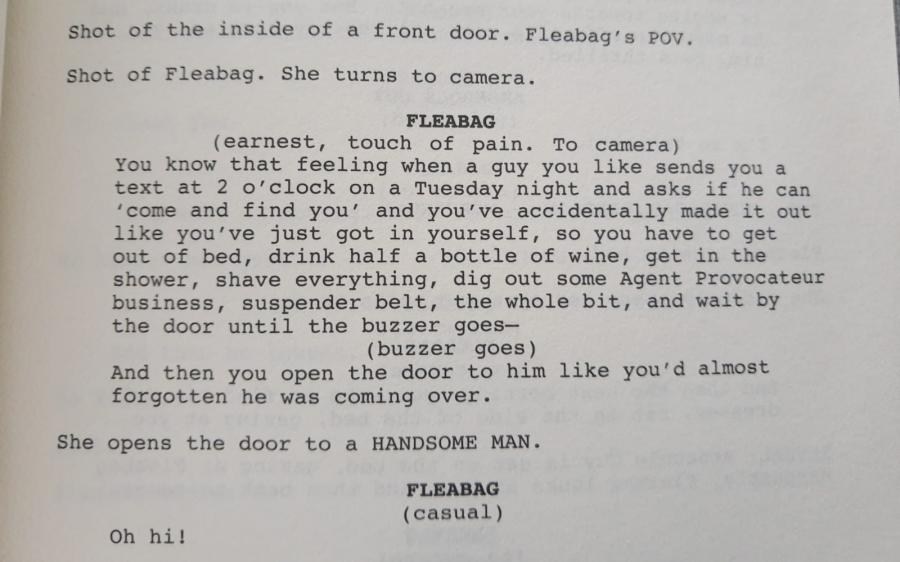

(3) When narrating what is happening, Fleabag gives the viewer both more context and some guidance for interpretation. She lets the viewer know what the right way of interpreting the scene or context is. When we find Fleabag standing in front of her door in the middle of the night, smudged makeup and hair half-done, it might be unclear to the viewer what to make of this moment. Thankfully, we have Fleabag’s commentary to help us out here (see picture below). Now we know: Fleabag is waiting for a guy while pretending to have partied the whole night.

Opening Fleabag.

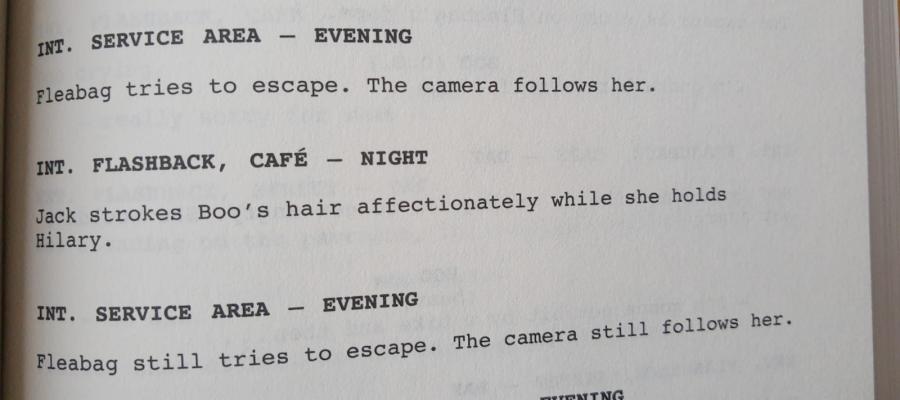

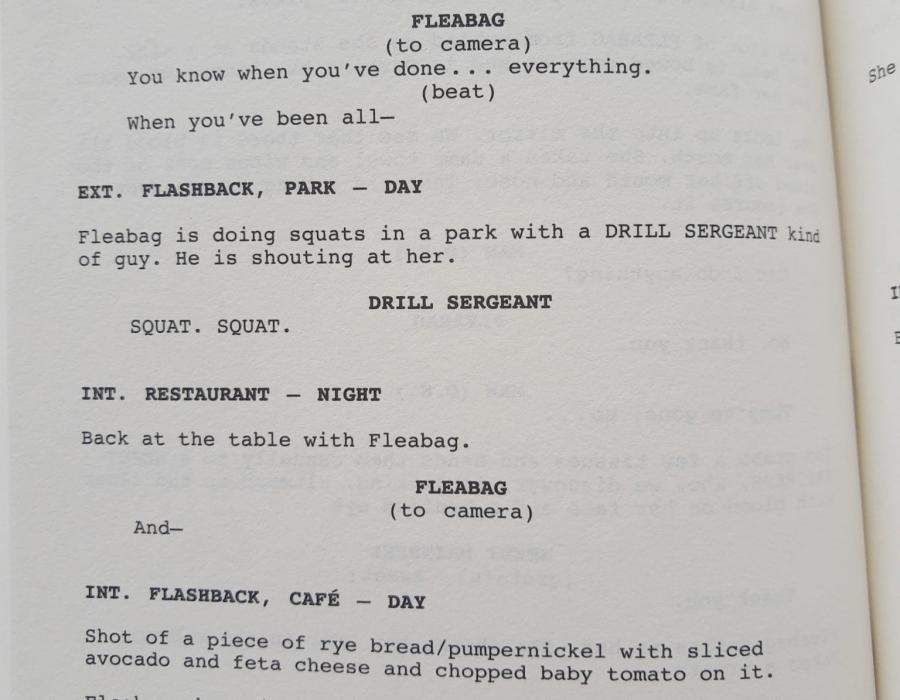

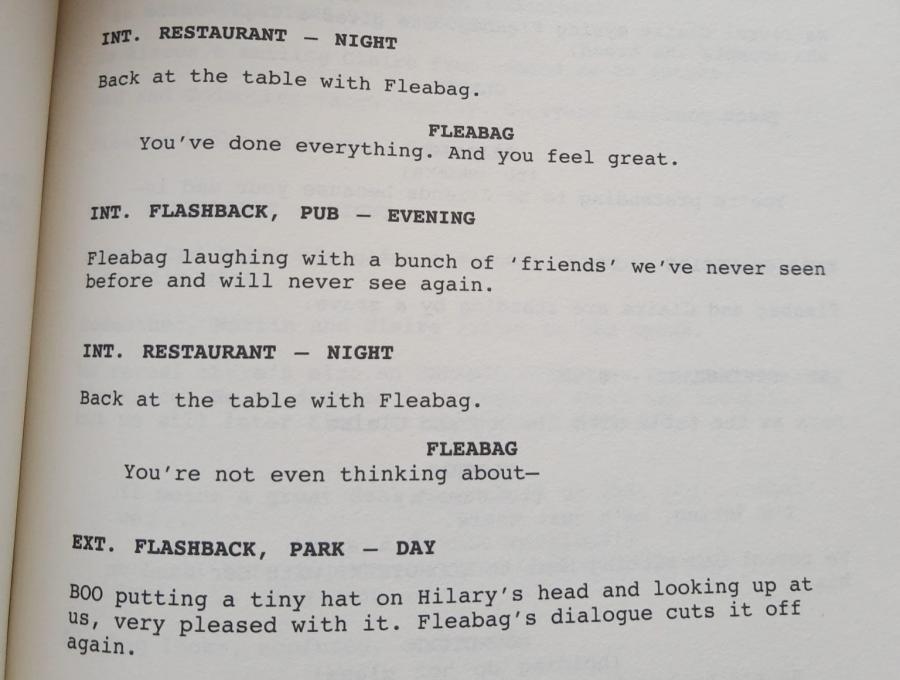

(4) In order for us to extract more information about the past, the series shows us flashbacks. These flashbacks can serve both as new information - for example, memories of Boo - and as a reminder of things that we have witnessed before but should not forget. At the start of the second season, this latter function gets used quite often in order to ease the viewer into the series again and give them an update on where we are after the first season ended. Below, you can see how this scene was written down as well as performed on screen.

A flashback.

A flashback.

How Fleabag creates intimacy by breaking the fourth wall

Through using scenes and looking at the scriptures, this article has analyzed Fleabag's uses of the fourth wall, the kind of intimacy it builds, the position of the viewer, the balance of intimacy and distance, and the role of narrativity in the show. Besides serving as a comedic device, Fleabag actually "needs" the audience to like and distract her. Balancing these two worlds is not always easy and leads to moments of both intimacy and distance, as Fleabag internally struggles with feeling both proud and ashamed of "us". The way Fleabag narrates her life helps the viewer connect the dots and get to know Fleabag more, for better or worse. In conclusion, through breaking the fourth wall Fleabag is able to both create and destroy intimacy, which leads to much confusion on both Fleabag's and the viewer’s side about the degree to which this relationship is actually two-sided.

References

Brown, T. (2013). Breaking the fourth wall. Edinburgh University Press.

Ettenhofer, V. (2019). How ‘Fleabag’ bridges the gap with the fourth wall. Filmschoolrejects.com

Fleabag. (2016-2019). TV series. BBC.co.uk

Killian, K.D. (2019). Painful perfection: review of the tragicomic series fleabag. Psychologytoday.com

Lionheart Theatre. (2016). Breaking the fourth wall - what it is, why people avoid and why some don’t. Lionhearttheatre.org

Rivera, R. (2014). Pros & Cons of breaking the fourth wall. Writeonsisters.com

Reddit. (2019a). What’s up with the priest semi-breaking the 4th wall? Reddit.com

Reddit. (2019b). Has anyone analysed what exactly breaking the fourth wall signifies? Reddit.com

Reddit. (2019c). Significance of priest calling fleabag out on breaking the 4th wall? Reddit.com

Springer, J.P. (Ed.) (2005). Docufictions: essays on the intersection of documentary and fictional filmmaking. McFarland.

Strawson, G. (2004). Against narrativity. Ration, 17(4), 428-452.

Tvtropes. (2020). Breaking the fourth wall. Tvtropes.org

VanArendonk, K. (2019). Fleabag breaks the fourth wall and then breaks our hearts. Vulture.com

Waites, K.J. (2015). Sarah Polley’s Documemoir Stories We Tell: The Refracted Subject. University of Hawai’i Press.

Waller-Bridge, P. (2019a). Fleabag: the scriptures. Penguin Random House.

Waller-Bridge, P. (2019b). Phoebe Waller-Bridge: why acting in ‘Killing Eve’ ‘Just Didn’t Feel Right’. The Hollywood Reporter.

Wikipedia. (2020). Fleabag. Wikipedia.org

Wong, D. (2019). Distancing affect in Fleabag. Alluvium Journal, 7(5).

Wright, C. (2019). ‘Fleabag’: Phoebe Waller-Bridge says this is the real reason her character talks into the camera. Cheatsheet.com