Pokémon Go as a Self-Tracking Application

17 years after John Siegler and John Loeffler wrote the famed lyrics for the Pokémon Theme, Pokémon Go was introduced.

While the anime theme song was originally written as the enthusiastic monologue of a dedicated Pokémon trainer, for many trainers in Pokémon Go, not only do they wish to be the best in taming these creatures but also to become the best versions of themselves through adopting an active lifestyle. Numerous Pokémon Go weight-loss stories have been shared online and on social media since the application’s initial launch in 2016. Many users of the application have experienced healthy transformations via immersing themselves in the world of Pokémon Go.

Google entries of Pokémon Go weight-loss stories

Following the trail of breadcrumbs left by these Pokémon Go trainers, this article will seek to understand the application as a self-tracking application through which individuals are able to achieve wellness, instead of viewing it purely as a mobile game. More specifically, I will utilize the concepts of self-surveillance and the reflexive monitoring self (Lupton, 2014) and examine how Pokémon Go motivates users to continually engage in these self-tracking practices through elements of gamification.

Pokémon Go

As a collaborative project between Niantic, The Pokémon Company, and Nintendo, Pokémon Go is a mobile application that employs augmented reality (AR) technology to bring Satoshi Tajiri’s creations to life. With the click of a button, individuals are able to spot various species of Pokémon in their vicinity through the camera lens on their devices, as if they are hidden in plain sight for users to discover. In addition, the application makes use of the Global Positioning Systems (GPS) that are built into our portable devices, e.g., smartphones and tablets, to cartographically compose a map of our geographical location on which we are able to interact with the application’s three essential components:

- The Pokémons, or the creatures that are intended to be caught.

- Gyms, which are specifically designed spaces where skirmishes between Pokémon can occur.

- Pokéstops, where players can “spin” to collect items that assist them in successfully catching the little beings.

The fundamental design of Pokemon Go's interface

Since its release in 2016, Pokémon Go has been one of the most successful mobile applications worldwide, reaching over one billion downloads across iOS and Android platforms as of March 2019. Even more interesting, however, is that at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in 2017, Niantic reported that Pokémon Go users across the globe have cumulatively walked 8.7 billion kilometers (Iqbal, 2020). To put this in perspective, the furthest planet in our solar system, Neptune, is approximately 4.5 billion kilometers away from the sun (Cain, 2009). If one imagines the entire Pokémon Go user base as a dutiful astronaut, they have already accomplished the incredible feat of traveling to the end of our solar system and back.

Similarly, Althoff et al. (2016) researched the application’s impact through measuring the alteration in physical activity before and after using Pokémon Go among 31,793 Microsoft Band users who resided in the United States. The results of their study show that there was a significant increase in participants’ physical activity over the course of 30 days. Moreover, they noted a dramatic 26% increase in average activity for some exceptionally-engaged Pokémon Go users (Althoff et al., 2016). Simply put, the developers of Pokémon Go have certainly accomplished the task of encouraging users to embrace an active lifestyle.

Surveilling ourselves

Fundamentally, the origin of self-surveillance can be traced back to the concept of the panopticon. First introduced by Jeremy Bentham, it was later adopted by Michel Foucault as a metaphor for disciplinary power in modern Western society in his 1975 work Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. The panopticon design is a system of control in which an individual or state has the ability to observe and monitor people in excruciating detail, without them being able to distinguish whether they are currently under such a gaze or not. As a response to the knowledge that one could be scrutinized at any given moment, the surveilled subjects in turn surveil themselves. In other words, they are more attentive to operating within the sociocultural norms and boundaries set by the observer, who is of a higher social strata.

Vaz and Bruno (2002) expand the panopticon concept to include not only self-surveillance practices induced by the watchful eyes of the powerful but also those originating from an innate desire to “constitute themselves as subjects of their own conducts”. Underpinning this demand for care of the self are the culturally-bound conceptions that certain behaviors are “dangerous or unwholesome”, and that individuals must take responsibility for working on those parts of themselves that would be considered as such (Vaz and Bruno, 2002, p.273).

In this regard, self-surveillance entails both self-awareness of one’s failure to meet certain cultural expectations and the voluntary action of monitoring oneself in order to deal with these underperformances.

In the digital era, constantly-evolving technologies have brought along an ever-expanding repertoire of digital affordances that give people the ability to self-monitor in an increasingly detailed manner. As a result of such developments, we are noticing an emergence of what Lupton (2014) describes as “the reflexive monitoring self”, which is a mode of selfhood that utilizes a combination of “regular and systemised digital information collection, interpretation, and reflection as parts of working towards the goal of becoming” (p.12).

More precisely, a reflexively self-monitoring individual notices shortcomings they would like to attend to, e.g., losing weight, managing their time better, or alleviating stress. Then, as a means to these ends, they “collect” personal data through self-tracking apps and formulate an “interpretation” of their physical or mental wellness. Based on this evaluation, individuals “reflect” upon what they could do to enhance their well being. The cycle restarts as individuals regularly and systematically gather personal data which they interpret and reflect on.

Reinforcing this reflexive self-monitoring process is not only a belief in care of the self, which, as mentioned earlier, emphasizes individuals being self-aware and accountable for their own lives. It also stems from a sense of self-entrepreneurship, or people “improving their life chances,” which has arguably been a dominating ideal in the social media age (Lupton, 2014, p.12). Moreover, although reflexive self-monitoring could be conducted alone, or as Lupton has termed it, private self-tracking, following the participatory culture of Web 2.0 is an upsurge in communal self-tracking. It involves the formation of online communities in which self-tracking individuals share their experiences in order to become better selves together. Hence for many of these self trackers, self-reflection entails not only reflecting on their own data but also on how they can present their observations to other like-minded netizens (Lupton, 2014).

Gamification and self-tracking applications

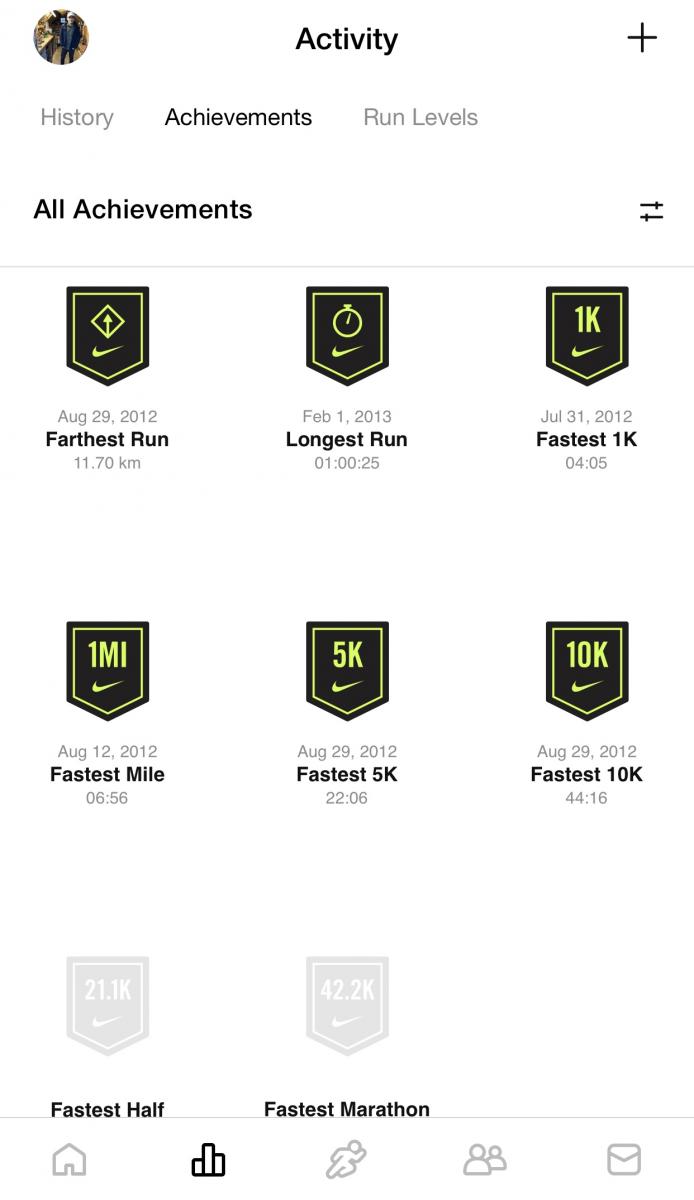

It is also important to note that most self-tracking applications, e.g., Fitocracy, Nike+, and Gymskills, are not solely pedometers. Instead, the applications often incorporate elements found in video games, such as scoreboards and achievement systems, in order to motivate and incentivize their users to continuously track their physical activities. Implementing fundamentals of video game design in different fields is commonly known as gamification.

Nike+'s achievement system

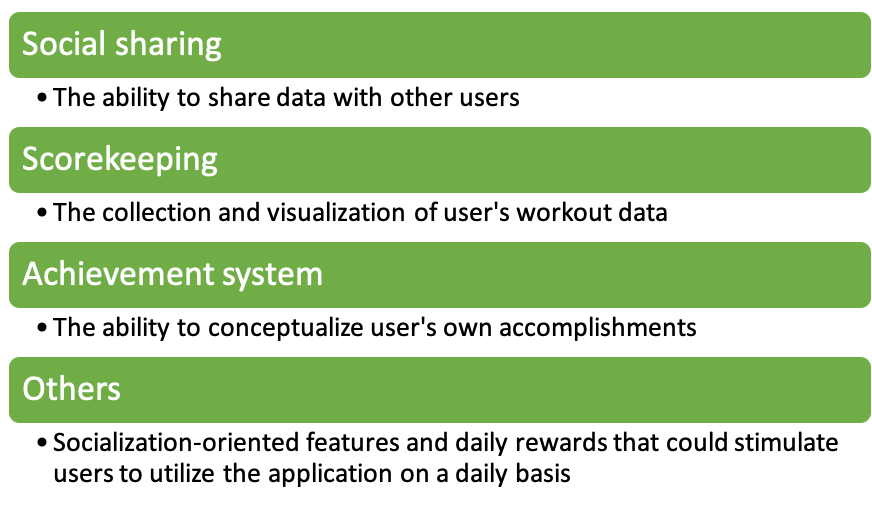

The idea of utilizing video games for fitness purposes is not a recent development, as games like Nintendo’s Wii Sports have already demonstrated their potential. However, concept of fitness gamification, defined by Wylie (2010) as “employing game components to motivate individuals to reach their personal health goals” (p.1) has only recently emerged alongside smartphones and mobile applications. Wylie has identified four elements of gamification that are commonly found in successful self-tracking applications:

The four elements of gamification located in successful self-tracking applications (Wylie, 2010)

Apart from the growing ubiquity of gamified designs among self-tracking mobile applications, it is important to bear in mind is that these instruments for reflexive self-monitoring do not merely accumulate personal data but all work towards promoting and encouraging tracking physical activity through gamification (Wylie, 2010, p.5).

Pokémon Go as a self-tracking application

Pokémon Go has been publicly viewed as a location-based “game” and has been categorized as such in both Apple’s App Store and the Google Play Store. Yet it could equally be understood as a “gamified” self-tracking mobile application that motivates users to not only engage in but track their physical activities through its video game design.

Pokémon Go being categorized as a "game" in both Apple's App Store and Google Play Store

First and foremost, one underlying critique to resolve is that if “Pokémon Go is essentially a mobile game, how could it be regarded as a gamified self-tracking application?” If we consider the previously-mentioned example of Nintendo’s Wii Sports, it would not be classified as gamification since it is in essence a video game, rather than a self tracking app with game features. Pokémon Go, however, could fall within the boundaries of gamified self-tracking due to its core ideology of motivating and tracking physical activity, which is very much in line with Wylie’s (2010) observation that these mobile applications all encourage their users to engage in physical activity. When asked what he was trying to achieve with Pokémon Go, Niantic’s CEO John Hanke stated that,

“...our goal is to make a positive impact on the world by using those principles when we develop our products. And the principles are to encourage exercise, exploration, discovery of new places and real face-to-face social interaction” (Ogawa, 2016).

In addition, Adventure Sync, which was implemented in November 2018, supports Pokémon Go’s belief in encouraging outdoor physical activity. By turning on this optional feature, users are able to not only track their distances travelled but earn rewards for corresponding walking milestones without opening the application. As Paul Franceus (2018), one of Niantic’s senior software engineer explained, the goal of Adventure Sync is to allow users to “capitalize on the dead time that manifests when they forget to launch the app, earning credit for exploring the world and developing a solid motivation loop that requires nothing except a smartphone”.

Adventure Sync's user interface

Through Adventure Sync, Pokémon Go mainly functions as a self-tracking application that continuously records users’ workout data, including kilometers walked, steps taken, and calories burned. Furthermore, Niantic’s willingness to implement a feature which to an extent casts aside the main attraction of Pokémon Go as a location-based game could be viewed as an indication that the application is purposefully designed to be not a game but a gamefied self-tracking application.

Significantly, there are also instances where Pokémon Go users utilize the application as a self-tracking instrument in their endeavours to adopt a healthier and more active lifestyle, as documented on different socio-technological platforms.

Through some rather straightforward keyword searches (e.g., “pokemon go+lose weight”) on YouTube, I found individuals who posted video content about how they became healthier through using Pokémon Go.

Results for the search query "pokemon go+lose weight" on Youtube

For example, in a video titled “Pokémon Go Diet: How i walked 185km and lost 18lbs in 15 Days!”, YouTuber Ty Go Walk’s records his weight loss plan. According to the vlogger, his idea was to walk a minimum of 10 kilometers every day while using Pokémon Go. To briefly summarize the video, Ty Go Walk reports that he had walked 100 kilometers during the first week and 85 kilometers during the second week, adding up to a total mileage of 185 kilometers since the vlogger initiated his workout plan. Additionally, to illustrate his efforts, Ty Go Walk edits in a screenshot of his progress for the Jogger medal, which indicates the total amount of walking distance since he began using the application.

Vlogger Ty Go Walk reporting his weekly walking mileages through Pokémon Go's medal system

Without further ado, the vlogger then stands on the scale and finds that he had lost 5.2 pounds since his first-week weigh-in. While he is somewhat disappointed, since he had lost 13 pounds the week prior, the vlogger explains that since he was attempting to lose weight without unhealthily starving himself, the five-pound weight loss is still considered successful. Ty Go Walk finally states that he will continue with his daily Pokémon Go walking sessions as the application is a “fun walking companion.”

As we can observe, not only Ty Go Walk’s workout plan but also the recording of such is very much in line with the reflexive self-monitoring process. Triggered by an innate intention to attend to his health, the vlogger first gathered workout data through the use of Pokémon Go, most notably through the Jogger medal in the application’s medal system. Next, he set this piece of information side by side with his weight measurement, so as to draw the conclusion that he had lost 5.2 pounds that week. Based on this interpretation, Ty Go Walk then reflects that the weight loss could be deemed successful, and he resolves to persist in walking 10 kilometers everyday while playing Pokémon Go. Last but not least, in the spirit of communal self-tracking, the vlogger records and uploads the video on YouTube in order to share his ongoing progress and personal insights with his fellow netizens.

Another example of this reflexive self monitoring mentality is the fitness-related subreddit r/loseit, where individuals not only collect, interpret, and reflect upon their private data collected through Pokémon Go, but in accordance with communal self-tracking, present their intimate stories and progress to others.

"I feel like I'm on the right track after my first month. I'm learning a lot."

In a post titled “I feel like I’m on the right track after my first month. I’m learning a lot”, Lily-of-the-Lake offers us insight into their weight-loss journey. The redditor begins with some reflections on their diet changes, including what they are currently doing and hope to accomplish later on. They then inform us about their ongoing workout plans, which consist of relearning a belly dancing choreography and walking/hiking. What is noteworthy is that Lily-of-the-Lake then reports that they have been incoporating Pokémon Go into their outdoor walks. They have consistently received the “25km a week medal with a bit to spare” yet would like to receive the 50 kilometers a week medal. Additionally, the author reflects that their current walking speed is too slow to meet the fifty-kilometer-a-week goal, but they intend to gradually dial up their walking pace to reach the target mileage.

By creating this reddit post, Lily-of-the-Lake exemplifies the reflexive monitoring self. Triggered by a sense of responsibility for their own wellness, the author takes part in the cycle of accumulating private data, in this case their total walking mileage as tracked by Pokémon Go, then interpretating that they currently can walk/hike approximately 25 kilometers a week, and finally reflecting on their condition and future goals and concluding that through a boost in walking pace they could reach 50 kilometers a week.

From a developer's perspective, the application arguably falls under the classification of self-tracking applications on two grounds. As indicated by John Hanke’s statement, Pokémon Go’s central ideology entails the promotion of physical activity, which is consistent with most self-tracking applications. Moreover, the implementation of Adventure Sync further enhances Pokémon Go’s self-tracking capacity by giving users the option to track themselves by merely installing the application on their mobile devices, .

By examining user-generated content on platforms like YouTube and Reddit, we also uncover cases where individuals consciously appropriate Pokémon Go as a self-tracking application. Users gain insight into their exercise sessions and motivate their physical activities with relevant rewards in their reflexive self-monitoring procedures. All in all, while Pokémon Go is publicly regarded as a mobile game, the application works beyond such simplistic categorization in that not only is it intentionally designed but practically utilized as a self-tracking application that possesses the capability to enhance individuals' well-being.

Gamifying self-surveillance

As previously established, gamification has been a trend among self-tracking applications, or as Wylie (2010) specifies, fitness gamification. Much like its self-tracking app contemporaries, Pokémon Go heavily utilizes gamified designs in its efforts to motivate its users to perform and keep track of their physical activities. By personally partaking in Pokémon Go and its culture, I was able to identify four major elements of gamification that could potentially encourage individuals’ recurrent engagement.

Social sharing

Firstly, through the social features of Pokémon Go, users are able to add friends and network with others by either inputting friends' “trainer codes” or connecting Pokémon Go to their Facebook accounts.

Pokémon Go's users are able to befriend others through sharing their "trainer codes" or linking their Pokémon Go account to their Facebook account

Once trainers become friends with one another, they are able to share two sets of private data. First, users’ total walking mileage, which is a key piece of self-tracking data, is easily noticeable in their profile and can be accessed by clicking on the relevant entry in their friends list.

Total amount of walking distance presented in user's profile

The second set of information revolves around the specific geographic locations individuals visit while playing Pokémon Go. Through the gift-giving feature, trainers can send each other 'presents' that are gained by spinning Pokéstops, or virtual representations of certain real-life locations. These presents not only contain handy in-app items such as Pokéballs, but more importantly, the exact locations where individuals obtain the gifts are shown when receiving users to open them.

"Gifts" that show the user's visited geographical location

Scorekeeping

As for the gathering and presentation of Pokémon Go’s users workout data, not only are walking distances presented in the application, but it utilizes an experience point (XP) system in which each action in the application has been assigned a given amount of XP. Examples of the actions that are accounted for within the system include catching Pokémons, visiting Pokéstops, or hatching Pokémon eggs.

Pokémon Go's experience point (XP) system

It is important to note that these interactions within the application all require to a certain extent the performance of physical activities. As both Pokémon and Pokéstops are randomly distributed in the wild, trainers have to go outdoors to play. Not only is it highly unlikely that trainers would be able to “catch ‘em all” by simply lying on their couches, but they must also visit the real-world locations that Pokéstops represent in order to store up items that assist them in capturing Pokémon.

Further, Pokémon eggs can only be hatched by reaching certain walking milestones. A designated pool of Pokémon hatch when 2, 5, 7, or 10 kilometers of walking distance have been accomplished. Users are motivated to perform various outdoor activities knowing that these virtual prizes are ahead of them.

The egg hatching feature in Pokémon Go

Achievement system

Consistent with other gamified self-tracking applications, Pokémon Go enables the conceptualization of users’ progression through an achievement system. Essentially, medals are related to different accomplishments within the application; for each of these, users complete an initial objective to receive the bronze medal, then must complete three additional tiers of objectives to progress to silver and gold medals.

Pokémon Go's medal system

One of the more telling examples is the aforementioned Jogger medal, which is tied to users’ walking milestones. In order to first receive the medal, individuals have to walk 10 kilometers total; to upgrade from bronze to silver, a sum total of 100 kilometers is needed. Finally, to progress from silver to gold, 1000 kilometers is required.

The Jogger medal

Coming back for more

As Wylie (2010) states, self-tracking applications also rely on other features that utilize either socialization or periodic rewards so as to sustain their user base. In line with these strategies, the developers of Pokémon Go have implemented features that focus on constructing meaningful interactions between users and also provide rewards and seasonal events to dedicated trainers.

Firstly, the implementation of the previously-mentioned gyms has given individuals the opportunity to socialize with other trainers. Specifically, during the creation of one’s Pokémon Go account, one has to choose one of three teams, Instinct, Valor, or Mystic.

Team Instinct, Valor, and Mystic in Pokémon Go

This selection of one's team is significant, as trainers of the same team place their Pokémon in the virtual gyms so as to defend them. On the other hand, individuals representing the same team have to work together to take down gyms that have been occupied by opposing teams and populate them with their own Pokémon. In short, it is through such negotiation and interplay between the three competing teams that socialization between Pokémon Go’s users is constructed.

Gyms in Pokémon Go

Serving as bonuses for constant engagement are the “shiny” Pokémon. Known as 色違い in Japanese, they are Pokémon “with different coloration to what is usual for its species” (Bulbapedia, n.d.). Shiny Pokémon are extremely rare, with an encounter rate of 1 in 450 (The Silph Road, 2018). As such, “shinies” are considered valuables prizes for some of the most hardcore Pokémon collectors. Individuals who wish to get their hands on these creatures would have to embark on endless scavenger hunts in Pokémon Go.

Comparison between regular and shiny Pokemon

Last but not least, in January 2018, Niantic introduced Community Day, which is a monthly event featuring an increased spawn of particular Pokémon and their shiny variants. During the special event, trainers are motivated to go on outdoor adventures with their peers not only to capture exquisite shiny Pokémon but also to “celebrate what it means to be part of the Pokémon Go community” (Niantic, 2020).

Community Day in May 2020, featuring Seedot

The water that swallows the boat is the same that bears it

In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, Shoshana Zuboff has referred to Pokémon Go as an illustrative example of surveillance capitalism, which she characterizes as a “new economic order and logic” that utilizes the collection of personal data to account for human behaviors and experiences. Furthermore, this knowledge, which oftentimes involves the interpretation, tracing, and prediction of behavioral patterns, in turn can be appropriated for advertisements and strategic marketing purposes (2019).

It is certainly difficult to deny that Zuboff’s standpoint, which perceives Pokémon Go as an instrument of manipulation and exploitation of individual’s private information, is viable. Yet as this article’s investigation has shown, the application could be more optimistically viewed as a gamified self tracking application that enables individuals to gain quantifiable data about their physical activities and work towards better versions of themselves.

All things considered, while it is tempting for journalists and scholars concerned with surveillance and privacy to conclude that Pokémon Go is a potential invasion of privacy that governments or corporations could capitalize on, the application's positive impacts should not be neglected.

References

Althoff, T., White, R.W., & Horvitz, E. (2016). Influence of Pokemon Go on physical activity: Study and implication.

Cain, F. (2009). How far is Neptune from the Sun? Universe Today.

Franceus, P. (2018). Developer insight: Encouraging exploration with Adventure Sync. Niantic

Iqbal, M. (2020). Pokemon Go revenue and usage statistics (2020). Business of Apps.

Lupton, D. (2014). Self-tracking modes: Reflexive self-monitoring and data practices [Paper presentation]. Imminent Citizenships: Personhood and Identity Politics in the Informatic Age, Canbera.

Niantic. (n.d.). Community day.

Ogawa, J. (2016). 'Pokemon Go' developer wants to make the world a better place. Nikkei Asian Reviews.

Shiny Pokemon (n.d.). In Bulbapedia.

The Silph Road. (2018). The shiny hunt: Honing in on shiny encounter rates (Part 1).

Vaz, P. & Bruno, F.. (2002). Types of self-surveillance: From abnormality to individuals ‘at risk’. Surveillance and Society, 1 (3), pp.272-291.

Wylie, J. (2014). Fitness gamification: Concepts, characteristics, and applications.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. New York: PublicAffairs.