PTT Gossiping Board as a Digital Public Sphere

While the concept of the public sphere has been a topic of heated debate in Western society, it is important to acknowledge that its framework could also be utilized in the examination of phenomena that take place on the other end of the world. In this article, I will use the notion of the public sphere and its modern metamorphosis to analyze the Gossiping Board on PTT, a site of discussion on a Taiwan-based internet forum developed by civil society, as a digital public sphere on which Taiwanese citizens can engage in dialogues regarding matters of general interest.

What is PTT

PTT is a grassroots internet forum founded by a group of National Taiwan University (NTU) students in 1995. Led by Ethan Tu (who went on to become a software engineer at Microsoft and later the founder of Taiwan A.I. Labs), they were able to develop the forum within the confines of their dormitory (Fandom, n.d.). While the medium, during its infancy, was mainly used by NTU students who were living in dorms or studying in the NTU’s Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, it has since blossomed into an internet forum with its own particular culture. With approximately 20,000 “boards” that focus on a variety of topics, ranging from NBA and marriage to the American television series The Big Bang Theory, the site has accumulated around 1.5 million registered users with 150,000 users active during peak hours (Liu, Chen, Hu, & Zhou, 2016).

The Gossiping Board, as the name suggests, is a board on which (insider) news with regard to public figures or events could be discussed (Gossiping, 2020). The site has been one of particular significance on PTT owing to its function as a center for public deliberation and the dissemination of information relevant to the Taiwanese public.

The Public Sphere

The public sphere was first conceptualized by Habermas (1991) to be a realm of critical rational debates where private men gather and discuss state affairs. Habermas drew much inspiration from the bourgeois class in the 18th Century. As a matter of fact, in the second chapter of Habermas' instrumental work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, he outlined a blueprint for a public sphere that was based on 18th Century bourgeois society:

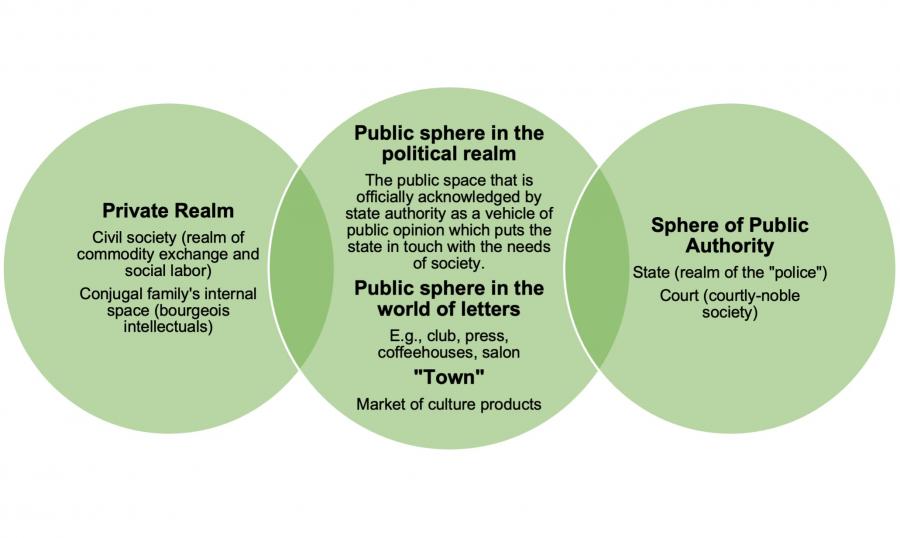

Figure 1: Blueprint for the bourgeois public sphere (Habermas, 1991, p.30).

This ideal of the bourgeois public sphere is of great importance in Habermas' work, as it offers a heuristic model on which the later development within the public sphere of Western society could be examined and critiqued (see Fuch, 2014, p.63). One main issue Habermas saw was the commercialized press. As the scholar explained, when newspapers “developed into a capitalist undertaking”, they also became vulnerable to “a web of interests extraneous to business that sought to exercise influence upon it” (1991, p.185).

More precisely, once the editors, which had been one of the main elements for the press as an institution of private men collectively forming public opinions in a rational and critical manner, were no longer independent from the publishers under the capitalist model of the press, the press became “the gate through which privileged private interests invaded the public sphere”. In other words, editors in the commercialized press have lost their capacity as private men engaging in rational critical debate in the public sphere, as the publisher would appoint editors in the expectation that they will do as they are told in the private interest of a profit-oriented enterprise (Habermas, 1991, pp.185-186).

The public sphere in the Digital Age

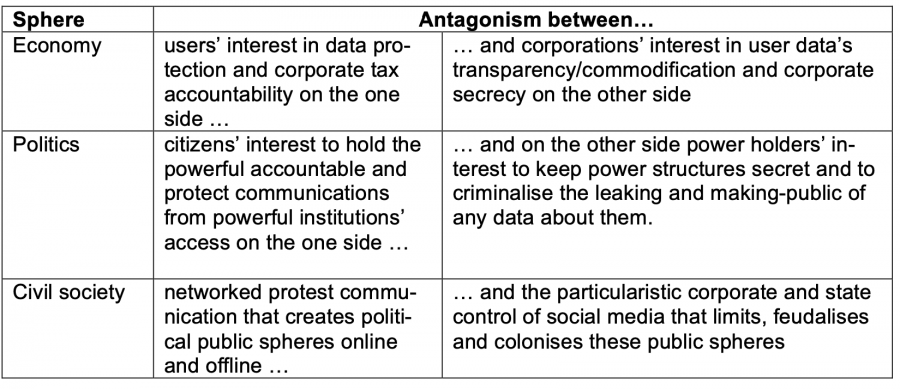

How could the public sphere be realized in the digital age? In line with Habermas, contemporary researchers such as Fuchs have argued that the solution could not be based on corporate social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter owing to their underlying commercial logic. As Fuchs (2014) has pointed out, there are three basic antagonisms when it comes to corporate social media (see figure below).

Figure 2: Three antagonisms of social media (excerpted from Fuchs, 2014, p. 76)

To combat these phenomena, Fuchs (2014) has suggested the fostering of public service social media that are run by government institutions, such as the BBC, or alternative social media that are run by civil society through “media reforms, participatory budgeting, and a reform of corporation tax” in the hope of stripping social media from the control of corporations and the state so as to truly harness the power of social media platforms as a public sphere (Fuchs, 2014, p.97).

The Gossiping Board as a Taiwanese public sphere: the case of the anti-red media

Following Fuchs, we shall delve into the examination of the PTT Gossiping Board’s functionality as a civil society social media on which a digital public sphere could be constructed. First and foremost, it is important to note that PTT fits Fuchs’ idea as a socio-technological platform that is free from the hands of commercialization. It could serve as a basis for a contemporary public sphere since it is not only clearly stated on the homepage for PTT that it will be an “academically neutral, non-profit, and non-commercial” as long as it exists (PTT, n.d.), but the founder Ethan Tu has publicly stated that he found the conception that PTT must follow the footsteps of Facebook and become commercialized unnecessary, for the essence of the platform does not lie in its net worth, but that it is a realm where netizens are encouraged to exercise their rights regarding freedom of expression to generate social change (Liberty Times Net, 2018).

Figure 3: No advertisement on PTT

With that established, we could investigate how the PTT Gossiping Board functions as a center for public critique on state affairs. In the following paragraphs, I will use the case of the anti-red media movement in Taiwan to illustrate its publicist function.

On 10/5, 2019, Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Yang held the Fourth Summit for Media People across the Taiwan Straits in Beijing. Among the Taiwanese media executives that have participated in the summit were several that held senior positions in the Wang Wang China Times Group, including the chairman of the media group, Tsai Eng-meng (Epoch Times, 2019). The Taiwanese media conglomerate has several media institutions under its wings such as the Taiwanese daily newspaper China Times, weekly (online) magazines China Times Weekly, and the television channel CTV and CTiTV.

It is important to note that the Wang Wang China Times Group has already been publicly recognized as a pro-China and pro-reunification corporation; thus its heavy involvement in such a high-profile summit between Taiwan and China already deserved to be the cause for some raised eyebrows vis-à-vis the Communist regime’s influence over the Taiwanese press. What was perhaps even more alarming, however, was the leaked recording of a behind-the-scene conversation between Wang Yang and several Taiwanese media executives, in which the former specifically instructed the latter to continue their work towards the reunification of Taiwan and China and that one could not predict what will happen to Taiwan in two years (Chou, 2019).

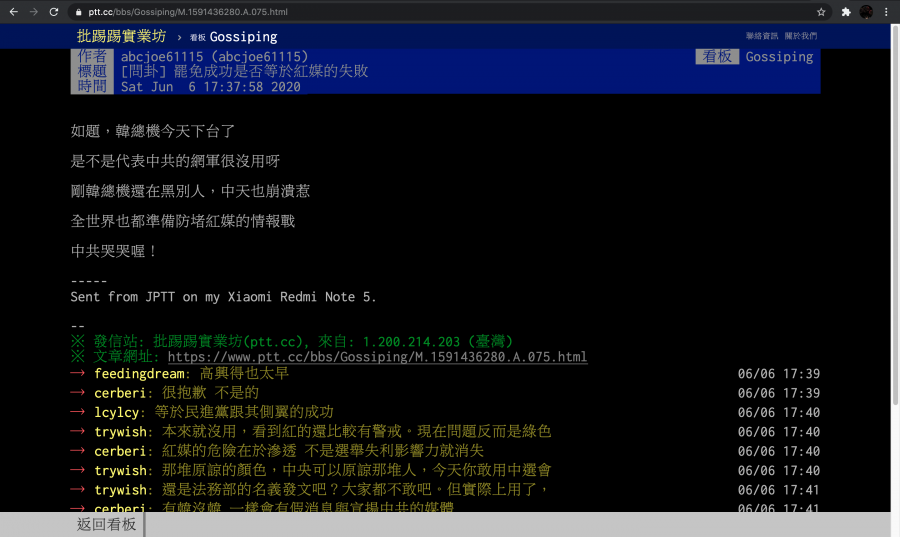

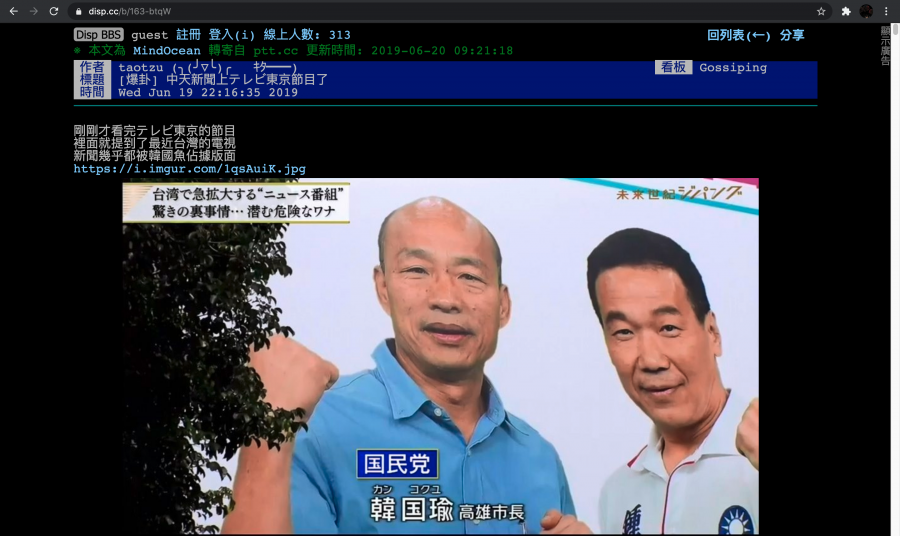

Additionally, on 19/6, 2019, a member of PTT’s Gossiping Board named taotzu, published a post regarding an exposé made by TV Tokyo regarding the abnormal amount of coverage about Han Kuo-yu, the China-friendly populist candidate who had announced that he would be representing the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) during the 2020 presidential election on the first of June.

In the piece broadcasted by the Japanese television network, one of the main discoveries was that some of the old-school Taiwanese snack bars had been almost exclusively showing the television channel CTiTV in their stores. The phenomenon turned out to be not a coincidence after all, as upon interviewing one of the owners of these snack bars, it was revealed that they were told by the cable company that they would receive a 600 New Taiwan Dollar (NTD) deduction in their monthly cable fee if they put on CTiTV.

Figure 4: taotzu’s post

In similar veins with such revelations and the raging Hong Kong protest, Taiwanese political influencer Chen Zhi-han announced on the 12th and politician Huang Kuo-chang later on the 13th that they were organizing a protest against pro-China media, which would take place on 23/6, 2019 (see Huang, 2019). Later named the Anti-Red Media Protest, the call for a public demonstration rallied over one hundred thousand people who were wearing white clothes (in opposition to “red”) on Ketagalan Boulevard to express their concerns with regard to the influential power of pro-China (red) media (Liberty Times Net, 2019).

In response, President Tsai Ing-wen posted on Facebook three days prior to the protest, reporting the efforts already done by the Taiwanese government in order to restrict the infiltration of the Communist regime, including amendments to the National Security Act, Criminal Law, and the Classified National Security Information Protection Act, which all in all aimed to implement harsher penalties for individuals who betrayed the country (2019).

In addition, under this larger framework of amendments, the New Power Party had proposed several then-undergoing-legislative-procedure amendments to the Broadcast Law, National Security Act, and the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area that specifically focus on individuals and organizations in the media industry who would like to manipulate the public as instructed or funded by the China Government (see New Power Party, 2019).

What is even more important is that even after the protest, the Gossiping board continued to perform its function as a public sphere on which the Taiwanese public’s common concerns over the Communist regime’s infiltration within the Taiwanese media were expressed. By searching for “紅媒“, the Chinese term for “red media” on the board, I discovered that from October 2019 to October 2020 (the month when this study is composed), with the exemption of February 2020, there has been at least one post on the board that was about the red media in Taiwan for each month (see figure below).

Figure 5: Results for the search string “紅煤” on Gossiping Board from October 2019 to October 2020

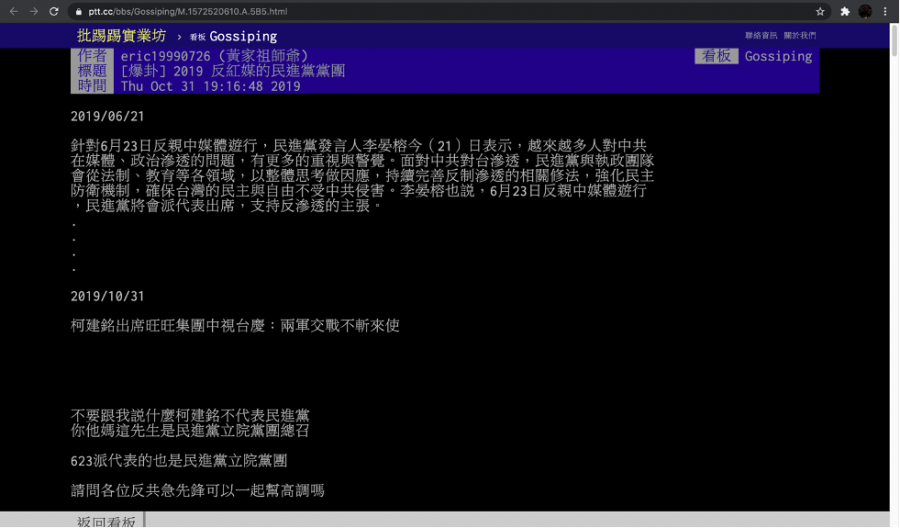

Among these posts, one main argument could be observed, i.e., while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), the ruling party during the investigated period, had stated that they would tackle the issue with the red media from various domains such as legislation and education (see Xie, 2019), there seemed to be a lack of effort in the actual realization of solutions. As eric19990726 has pointed out in his post published on 31/10, 2019, even though during the protest DPP had firmly announced their opposing stance with regard to pro-China media, Ke Jian-ming, the caucus whip for DPP, still made a public appearance for the 50th-anniversary celebration for CTV (the television channel managed by the Wang Wang China Times Group), which as mentioned earlier has been one of the major red media in Taiwan. Moreover, in one of the coverages for the extravaganza, Ke publicly stated that he has been close friends with Tsai Eng-meng, the pro-China entrepreneur in charge of the Wang Wang media group (Chen, 2019).

Figure 6: eric19990726’s post

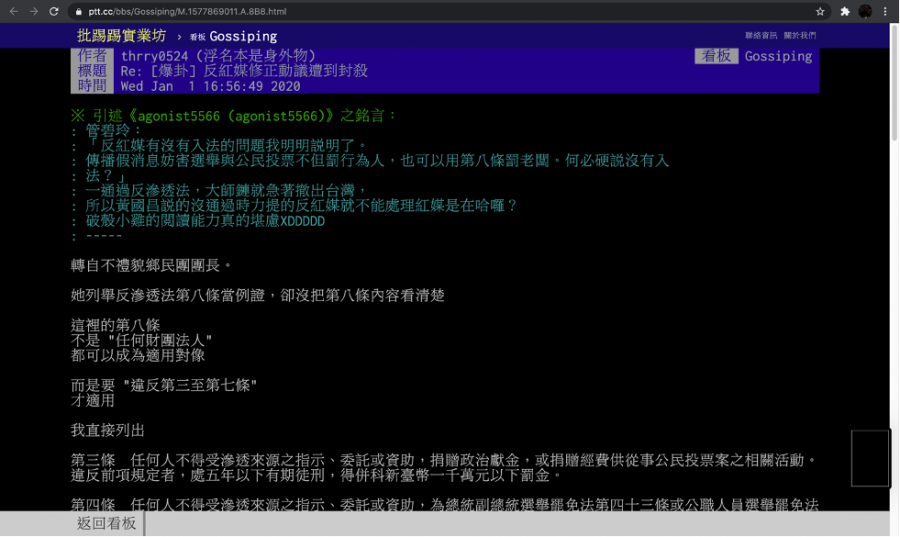

Additionally, the aforementioned “red media” amendments suggested by the New Power Party have been rejected twice in the Legislative Yuan, the unicameral legislature in Taiwan: once on 1/11, 2019, and the other on 31/12, 2019 (both instances were immediately reported on the Gossiping board). Moreover, as thrry0524 has suggested in his post published on 1/1, 2020, while DPP introduced the Anti-Infiltration Act in November 2019, which aimed to regulate activities funded or supported by opposing forces (the China government) that would potentially disrupt the integrity of democracy in Taiwan, whether such actions could be applied to the punishment of Taiwanese red media was questionable since there were no articles in this legislation that specifically addressed media institutions.

Figure 7: thrry0524’s post

As one can observe, by exposing and questioning state authority and powerful media institutions, the PTT Gossiping Board functions as a public sphere that intends to hold the powerful in check by examining various actors, even ones that are outside the country’s borders, within the hybrid media system (taotzu’s post about TV Tokyo), critically reflect the relationship between legislators and the corporation which they are supposed to regulate (eric19990726’s post about Ke Jian-ming), and thoroughly examining the implemented legislations to verify their efficacy (thrry0524’s post about the Anti-Infiltration Act). At the end of the day, whilst fact remains that over a year has passed since the 623 anti-red media protest and the future of the media field in Taiwan is yet uncertain, what may be certain is that members of the PTT Gossiping board will continually contribute to the public discussions, including those surrounding the red media.

Bringing the private to the public: the case of a missing child

One crucial transformation of the public sphere in the modern age is that matters of the family and household, which would be deemed as private for scholars such as Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas, have gradually been brought into the light of the public.

While Arendt would lament such circumstances as “both the public and private spheres of life are gone, the public because it has become a function of the private and the private because it has become the only concern left” (1958, p.69), Judith Butler would strike a more positive tone to the current situation. For Butler, one needs to acknowledge that in contrast to Arendt’s idea where not only matters of the “family and household” but necessities related to “the maintenance of life” such as the need for food and shelter shall remain hidden from the public realm (1958, p.28), issues as such should be reframed as political issues that require public discussion if we were to make sense of precarity, i.e., life's uncertainties such as poverty, the loss of our close ones, or undesirable living conditions, which we all might experience in some point of our lives (Butler, 2012, p. 147). In other words, just like traditional political issues such as the safeguard of democracy and freedom of expression are considered as public concerns, the dangers we might face as private men/women deserve attention in the public realm as well.

Figure 8:. Netizens asking for dashboard camera footages for car accidents (right) and information on missing persons (left)

Figure 8:. Netizens asking for dashboard camera footages for car accidents (right) and information on missing persons (left)

This necessary change to the modern conception of the public sphere can also be seen on the Gossiping Board, as there are often posts on the site in which netizens call upon the public’s assistance regarding private matters such as asking for dashboard camera footage for car accidents that could serve as evidence for their cases or a call for information on particular missing persons cases (see figure above).

Figure 9: Facebook group “Hsinchu Things”

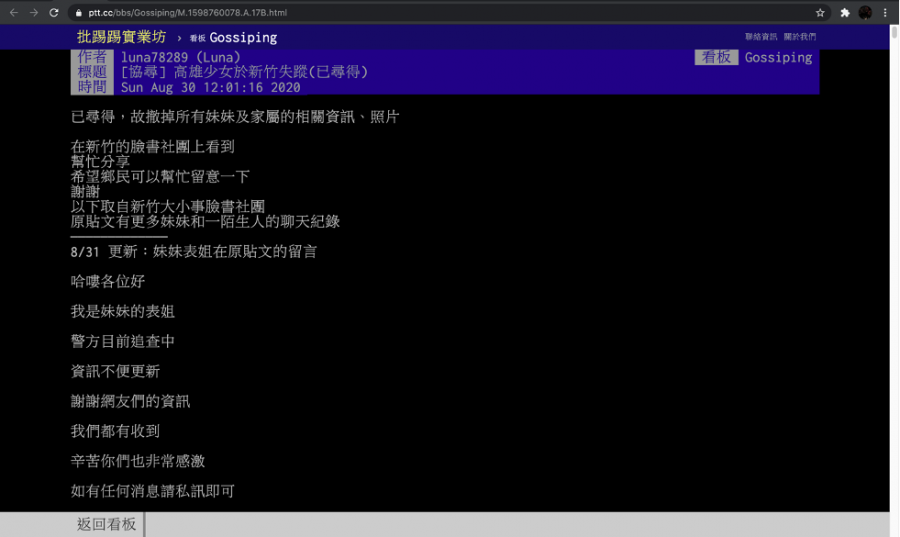

As a case in point, let us observe one particular missing person case that went viral on the Gossiping Board. On 30/8, 2020, luna78289 created a post titled “Teenage girl from Kaohsiung went missing in Hsinchu, need help”. In the post, the concerned netizen stated that he/she has seen a post on the Facebook group “Hsinchu Things” regarding a missing teenage girl and decided to share the Facebook post composed by the child’s mother on PTT’s Gossiping board as an open call for help in locating the missing girl.

Figure 10: luna78289’s post

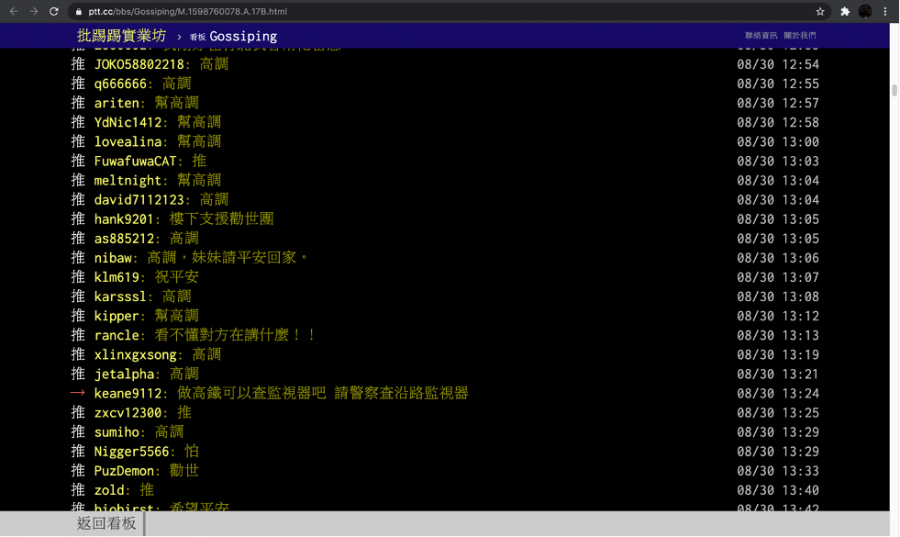

The post immediately gained traction, with over 100 members of the Gossiping board commenting on the post on the first day it was published. It is also interesting to note that among these members, several have not only “pushed” (推) the article, which is similar to “upvoting” on Reddit, but left the comment “高調“, a Mandarin phrase that means “high-key”, signifying that they wished to get the post trending on the board (see figure below).

Figure 11: Comments saying “高調” under luna78289’s post

On 31/8, 2020, a member of the board who went by the name of golang created a post in response to the news. To briefly sum up the article, following a phone number (0955-094-759) which could be seen in the screenshots of chat histories between the teenage girl and a man named Jiemin Wang originally made public by the worried mother, golang was able to locate a post on HOUSEtube.tw, a prominent Taiwanese house renting website, regarding an apartment that was available for rent in Hsinchu.

As detailed on the website, the housing information was published by Wang Zheng-hao, a man with not only the same last name (Wang) as the man who has been chatting with the missing girl, but also the same phone number. Additionally, an email address (pinkpingqqq@gmail.com) was presented.

The newfound information was consistent with what was already discovered by Sam Chen, who had reported under the original Facebook post that he has uncovered a Facebook account that was in possession of an identical phone number and went by the name Wang Zheng-hao. Furthermore, golang was able to uncover a post by Wang Zheng-hao in the Facebook Group “Everything housing in Hsinchu”, which similarly offered detailed housing information with regard to an accommodation located in Hsinchu.

While the relation between Wang Zheng-hao and the missing girl was already rather evident, what seemed the most suspicious, as suggested by golang, was that the Facebook account was deactivated soon after he posted his discovery on the Gossiping board.

Figure 12: golang’s post

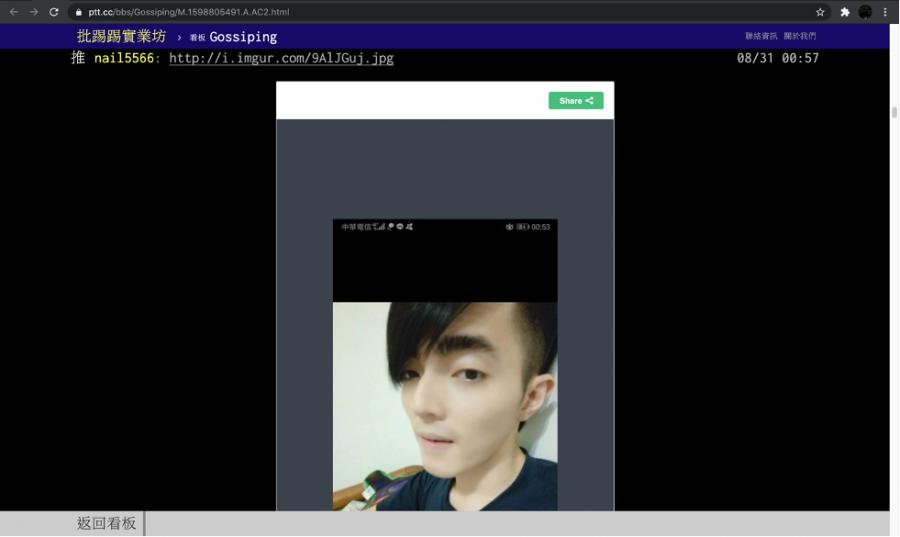

Shortly after golang’s post was published, numerous members of the community responded, with several of them chiming in on other leads they have found on the Internet. One such that turned out to be instrumental in the subsequent pinpointing of the missing teenage girl’s location was suggested by nail5566, who uncovered a picture of another potential suspect who went by the pseudonym Luo A’Ping through conducting a search on the phone number 0955-094-759 on the messaging app WeChat.

Figure 13: nail5566’s comment under golang’s post

In addition, 7 hours after nail5566 posted Luo’s profile picture on the board, Covera found the same profile picture on a twitch channel with the username Pinkping, which he located by searching for the aforementioned email address (pinkpingqqq@gmail.com) on the streaming platform.

Figure 14: Covera’s comment under golang’s post

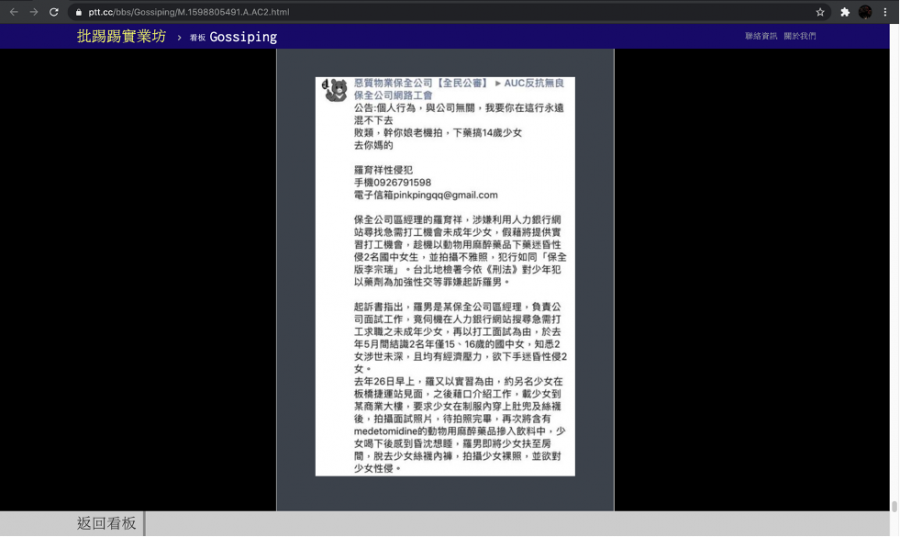

What would turn out to be the most troubling however, was that another member of the board WhyThe has reported that “Luo A’Ping”, whose real name turned out to be Luo Yu-xiang, had been accused of using 104, a prominent human resource website in Taiwan, to lure in two teenage girls, whom he later drugged and sexually assaulted, by promising them “internship opportunities”.

Figure 15: WhyThe’s revelation under golang’s post

Finally, on 1/9, 2020, following the trails of leads unveiled by members of the Gossiping community, the police were able to track down the missing girl, who had been imprisoned inside a secret room on the fourth floor of Luo’s apartment in Hsinchu. According to police reports, after several months of online messaging with the teenage girl, Luo eventually tricked the girl into taking a train from Kaohsiung to Hsinchu on the 29th with the assurance of a lucrative job. Upon arriving in Hsinchu, she got in a car driven by Lu, one of Luo’s accomplices, and was taken to Luo’s residence, which was co-managed by his other accomplice Wang.

After driving her to the designated location, Lu took the teenage girl’s cell phone and drove to Taipei in order to misdirect the police’s attempt to locate her through GPS phone tracking. At the same time, the teenage girl was imprisoned for 66 hours by Luo in the secret room. Furthermore, according to the girl, she was put on a shock collar by the criminal so that “she would behave” (Lin & Qiu, 2020).

As one can observe, the Gossiping Board, as a digital public sphere, is not only interested in political issues, i.e., the pro-China media, but private issues, i.e., the missing of a child. Furthermore, even though Miller has argued that a “crisis of presence” exists in the online world, that is to say, while “our social horizons, interactions, influences, and presences” has become less “spatially-limited”, our ethical assumptions still very much depends on bodily proximity (2012, p.281), as seen from this case of the missing teenager, Taiwanese netizens were very much capable of responding to the suffering of mediated others; this form of ethical obligation is one that a public sphere mainly facilitated through the internet desperately needs.

Here, yet always there

As Butler has suggested, in times of globalization (and digitalization) where the distant and the proximity are increasingly blurred, we need to recognize that we as human beings living in this world depend on one another for our existence, and that the only way to make sense of this bond is to have a mindset where “I am here and there, I am also not ever fully there, and even if I am here, I am always more than fully there” (2012, p. 149).

In other words, in order for a digital public sphere to function, inside the mind of each of us, there should exist a careful balance of attention towards matters that are close to our hearts and those to which we cannot immediately relate. It is not only that individuals, having experienced the ups and downs of having their own family and offspring or not, should attempt to understand the distress that comes from the potential loss of a child, but the fact that the joy comes from seeing the clumsily familiar silhouette of your children taking off their shoes when they got home from school could be taken away from you at any moment means that such issue should be a common concern that deserves discussion in the public sphere because “no one escapes the precarious dimension of social life” (2012, p.148).

PTT Gossiping, a digital public sphere

In this article, I examined the PTT Gossiping Board as a digital public sphere for Taiwanese citizens. First and foremost, in the same vein as Fuchs (2014), PTT, in its current state, is a socio-technological platform that is free from commercialization and advertisements; thus it could serve as a suitable infrastructure on which a public sphere could be built.

Aside from PTT’s non-commercial and non-profit promises, by examining the Gossiping Board through the lens of the public sphere, two layers of function could be observed. Firstly, in the case of the anti-red media movement, the site, similar to Habermas’ original formulation of the public sphere, serves as a center where not only private men could gather to discuss state affairs but also information of interest to the public could be disseminated.

Secondly, in the case of the missing teenage girl, in line with the modern transformation of the public sphere, i.e., bringing matters originally relegated to the private realm to the public, the board acts as a central hub where concerned netizens would gather and form a public think tank through which private matters of one’s family and household, e.g., car accidents and missing person cases, could be solved.

All in all, by analyzing how the PTT Gossiping Board has been performing as a public sphere for Taiwanese citizens, I hope to have offered a glimpse of what Fuchs’ idea of a public service/civil society social media platform-based digital public sphere would look like; considering PTT’s instrumental power in critiquing and questioning the state/media institutions and gathering concerned netizens together in an effort to resolve the precarious circumstances of others, it is surely an ideal that we should strive towards.

References

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Butler, J. (2012). Precarious life, vulnerability, and the ethics of cohabitation. The journal of speculative philosophy, 26 (2), pp. 134-151. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

Chomsky, N. (2002). Peace Netter: Interviewed by Hamish Mackintosh. The Guardian.

Fuchs, C. (2014). Social media and the public sphere. tripleC, 12 (1), pp. 57-101.

Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of Bourgeois society. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

Liu, Y., Chen, B., Hu, S., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Jiedu PTT: Taiwan zuiyou yingxiangli de shequn. [Understanding PTT, Taiwan's most influential social media]. BusinessNext.

Miller, V. (2012). A crisis of presence: On-line culture and being in the world. Space and polity, 16 (3), pp.265-285. DOI: 10.1080/13562576.2012.733568