The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław are fighting for art and democracy

The resistance group, 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław', is an organization that fights for art, freedom and democracy. This paper explores the group and analyzes a poorly-designed policy which negatively affects it. Further, this paper discusses how one man has tried to destroy real art in Poland by attackig one of the best theatres in the country: The Polish Theatre in Wrocław. The fight takes place in Wrocław (southwestern Poland), the European Capital of Culture in 2016, and also the city called 'WroLove' by Angela Merkel.

Introduction

Social movements can change norms, fight for values and set goals (Castells, 2015). Theatre-protesting movements in Poland have a long tradition. Before, during and after the Second World War theatre was the language of resistance. Nowadays, as the political situation in Poland is reminiscent of dictatorship, it is a weapon as well. The most recent Polish government has broken the constitutional law and it does not seem to care about the reprimands even given by the European Parliament.

The contents of the Polish Theatre art was often related to social, political or psychological issues. Sometimes actors decided to use the stage and manifest direct opposition against political decisions. For example in 2014, The Polish Theatre ended some performances with the protest, 'Theatre is not a product, and the spectator is not a client'.

In this paper, I will focus on the history of 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre' group. I will analyse the message of the group and describe the tools the group uses, including behaviorial, verbal and written acts. Being a member of the group puts me in special condition. On the one hand, it makes me more likely to fail in recognizing all the ideas (or ideologies) of the group (Blommaert 2005, p. 160). But on the other hand, participant observation and the theoretically informed analysis can give me an extra edge.

Freedom of speech under threat

Everything started two years ago during the liberal reign. The quality of living had increased. The country started to be more open-minded and free. Society had developed since Poland became independent from Russia (in 1989). Unfortunately, humans react with fear and resistance when their environment changes. The resistance mechanism is strong and can be useful for wariness, but it can also stop the process of change and development (Szlendak, Kozłowski, 2008).

'Our voice has been taken over – you can talk'

This is what had happened in Poland. The right-wing citizens started to defend what they called 'traditional values'. In Poland, these values are connected highly to Christian morality. The first significant scandal started in June 2014 in Poznań (west Poland), when 'Golgotha Picnic'—the performance by Rodrigo Garcia—was supposed to be shown during the Malta Festival, an international theatre celebration. The performance was never shown because the head of the festival was highly afraid of riots in the city; he decided to cancel the performance. Nonetheless, some Polish theatres decided to show video of the rehearsal. One of those theatres was The Polish Theatre in Wrocław, run by Krzysztof Mieszkowski.

Krzysztof Mieszkowski: Theatre reviewer, journalist, founder of art magazine, and director of TV and radio art programs. From 2006, the head of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław. From 2015, a member of parliament.

Art above divisions

More than one thousand people came to see the video of the rehearsal. Next to the long line of people waiting for the entrance, there was a Christian community group, singing and protesting.

There were no riots in Wrocław (like there were in other Polish cities because of the same event), probably because both groups could respect each other. Norbert Oczkowski, the Dominican priest who was protesting against the performance, spoke in public with Mieszkowski (the head of the theatre). The Dominican priest admitted that he had not seen the play. However, he already had formed an opinion about it. He claimed it offended his religious beliefs. The conversation was recorded and is available with English subtitles (in my translation).

Before the spectators were able to enter the theatre, Mieszkowski came out with a microphone and gave a short speech about freedom and respect. He said that he is happy that both groups (spectators and protesters) are here, and that both groups have right to express their beliefs. At that time, June 27, 2014, he could not have guessed that in two years, freedom of speech would be replaced with censorship in his theatre.

The spirit of the Polish Theatre in Wrocław

'If there was a reason, why Wrocław specifically deserved the title of 'The European Capital of Culture', the reason was The Polish Theatre in Wrocław.' Michał Urbaniak, the famous theatre reviewer, wrote this quote on his internet blog. Krzysztof Mieszkowski managed to build a collective that is famous and appreciated all over Europe. The Polish Theatre released plays like 'Holzfällen' by Krystian Lupa, based on Thomas Bernhard's text. It was an opening play during the last festival in Avinion and received a standing ovation (Ian Pelczar, 10.06.2016, Radio Wrocław). Urbaniak (2016) wrote: 'Even if the plays were not magnificent the spectators were always present, to discuss opinions, exchange ideas and inspirations. The spectators and The Polish Theatre in Wrocław team had a significant impact on each other.'

Beginning of censorship

In Autumn 2015, there was a parliamentary and presidential election. The right-wing citizens—the defenders of Christian morality and also the majority— voted a new government in power. What is more, Poland had chosen a right-wing president, who turned out to be a government puppet. At the same time, Krzysztof Mieszkowski joined the liberal democratic party 'Nowoczesna' ('Modern'). They got 6% and a place in government. Unfortunately, that was not enough for defending democracy, freedom of speech, and right to art. Shortly after the election, reality started to be different for Polish citizens and for The Polish Theatre and its spectators.

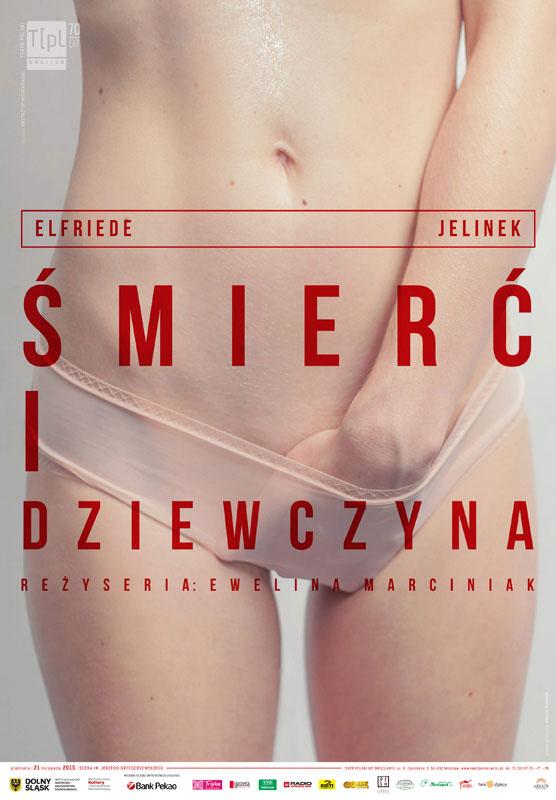

In 2015, another big scandal occured. Mieszkowski decided to make a play based on 'Elfriede Jelinek' ('Princesses dramas'), directed by Ewelina Marciniak. Those who know the text might not have been surprised that The Polish Theatre, besides own actors, hired pornography actors since the text contains nudity and intercourse. The play had no reason to be censored in The Polish Theatre, but critics thought otherwise.

In Poland there were some people who were shocked with the play's ostentatiousness, and the art provocation ended as a political scandal. The scandal was caused by Polish minister of Culture and Art, who declared on radio that he would ban the performance. What is more, he based his claim on the opinions of people, who had never seen the performance, nor had he.

The right to art won. The actors could perform, and the spectators could see the play. Most reviews said that the play was gentle, beautiful, aesthetic, decent, calm and well played (Katarzyna Mikołajewska, 23.11.2015). Unfortunately the joy did not last long.

Online community and real needs

In September 2016 Mieszkowski's contract for director of The Polish Theatre had ended. Everybody expected the contract to be prolonged. “You don't kill the goose that lays golden eggs”, do you? In February 2016 it was already known that Cezary Morawski would be the successor. Morawski is a Polish actor, known for playing in soap operas.

The Polish Theatre and its spectators are strong and confident that this candidacy is not acceptable. On the 28th of February, word became body. On the most popular social media platform, Facebook, a group was born: 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław'.

It is not certain who is behind 'The Spectators of the Polish Theatre in Wrocław' group. Maybe the founders prefer the group to stay an anonymous collective, or maybe they are afraid of making their personal data public. 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław' Facebook group counts more than 2500 people. Those are people mostly from Poland, but also from all over Europe. In the same year, another group appears on Facebook: 'Polski Theatre in Wroclaw in the Underground'.

Shortly after appearing on the internet, 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław' published an online petition to dismiss the nomination of Morawski. The Marshal Office did not react. On the 1st of September, Mr. Morawski took over The Polish Theatre (TP). For TP team and TP supporters it marked the beginning of a revolution. That day, actors decided on their first silent protest. With mouths covered with thick black tape, they stood in front of the audience, with sheets of paper in their hands. Everybody can read 'Our voice has been taken over – you can talk' (Janusz Wójtowicz, 1.09.2016, Gazeta Wrocławska).

That demonstration was an invitation to a discursive battle: to fight together, actors and spectators. Verbalization, including organizing resistance, protesting and criticizing is a political act (Maly, 2016). The first silent protest was an extraordinary, dual-purpose situation. Actors literally had given their voice to the spectators. The Polish Theater team managed to expose both being trapped in the state of helplessness, and manifesting an act of resistance.

'We are not giving permission for anachronistic, infantile theatre model'

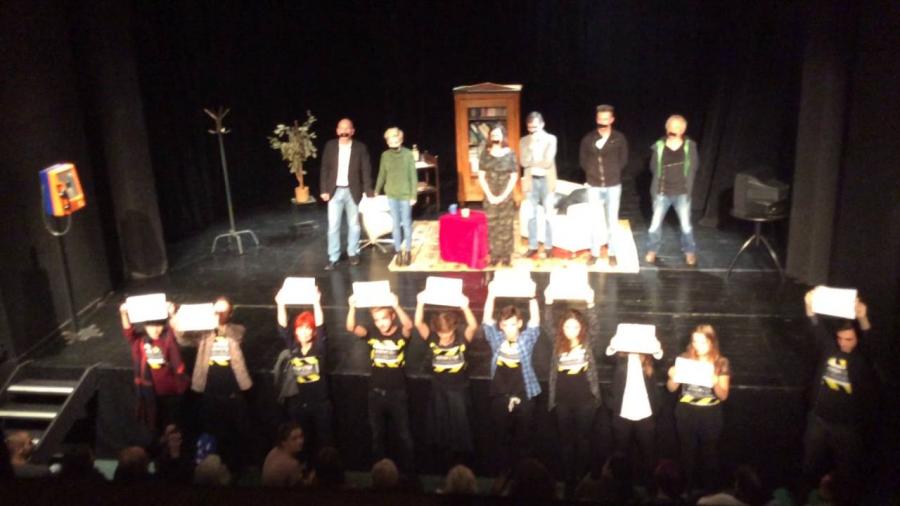

The actors did not need to wait long. On the September 23, 2016 'Death and the girl' was performed on stage. After the performance, TP supporters walked on stage to show the actors that they are not alone. This was just the beginning. More and more people continued to join (and are currently joining) the TP supporters. During the time of writing this paper, the Facebook group got several dozens of new members. In the name of the group, people are going to conferences, cultural meetings, interviews and discussions. On the 4th of October the 'Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław' was even interviewed on the Radio. Needless to say, the group is gaining momentum.

Morawski destroys something beautiful

However strong the TP side is, the fight is unfair. Cezary Morawski is not interested in discussions. His behaviour reminds us of Milgram's psychological experiments, where people started to behave brutally and violently (Aronson, 2011). His first deeds included: banning the media when trying to record the standing ovation of the silent protest at the end of the performance, turning off the lights on the stage in similar circumstances, and cancelling seven various plays. Furthermore, on the December 15, he fired 11 employees, including actors and directors. The actors shared their experience with the spectators, and the act was recorded:

The hegemony that Morawski introduced was shocking. Dictatorship and censorship is a precedent in free Poland (after 1989). Whoever was against his hegemony was on the list to be fired or treated brutally (Blommaert, 2005). The RAM Radio described a situation where Morawski did not let in an actress of The Polish Theatre into the building. Anna Ilczuk, with her two year old daughter in her hands, loved by Wrocław citizens, wished to see the play that she had directed, and she was not let in (sic!). Some dismissals have been given by Morawski, when the actors were still on the stage, or while using the toilet (Piotr Kaszuwara, 22.12.2016, RAM Radio)

Krystian Lupa, the director of 'Holzfällen' commented about the theatre's shifting dynamics. 'The spectators is a phenomenon. Till now they had appeared in the theatre anonymously, not knowing each other they used to seat one to another to participate in the reality of the performance. Now, when the seat of participation has been taken from them, they started to recognise each other'. (Magda Piekarska, 10.12.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza, in my translation). Mieszkowski raised a generation, making uncompromisingly high-quality art. That is why he has the spectators, who stand strongly by his side, said one of the TP supporters (phone interview with spectators, for Diggit Magazine). People want free art, and Mieszkowski, with his claims on the message, says that the current government tried to destroy The Polish Theatre from the beginning because they do not agree with The Polish Theatre art program. (Dorota Wodecka, 1.09.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza).

The power of artistic war

The current fight is about dismissing Morawski and recalling Mieszkowski. Existence of the internet group is sufficient for that. It is easy to collect signatures under the petitions via internet; communication is direct and fast. The weak point of this way of existing is an inability to organise live protest with the same amount of people because members are all over Europe (Maly, 2016).

Shortly after appearing on the internet, 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wrocław' published the first online petition for dismissal of the nomination of Morawski. The language that is being used is not designed to be received outside Poland. Protesters are using mainly Polish, even though the message has started to reach other countries. Thanks to internet, the protest is already international. 3312 people in Poland and all over the world signed the petition including Juliette Binoche, Izabelle Huppert and Peter Brook (Magda Piekarska, 29.11.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza).

However, is power simply about the numbers, or maybe also about the discourse? The claims about dismissing Morawski were supported by most democratic parliament groups, as the needs of the spectators are universal for all democrats (Dorota Wodecka, 1.09.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza). Morawski never could have become a part of the democratic team. He was very much the man of one message, his message. From the start he said that he does not have to listen to anybody, because it is his theatre, and he can do whatever he wants (Małgorzata Matuszewska, 16.12.2016, Gazeta Wrocławska).

Morawski could never be liked or accepted by The Polish Theatre team or by its supporters. He does not look like he is from the team. He does not speak like he is from the team. He did not use the proper language to communicate with the team. With his experience of being a soap opera actor, without any theatre successes, he started with a very unsuitable image. With the ideas of the art program and style of running the theatre, he was never on message (Lempert & Silverstein, 2005). Morawski came out with ideas of plays that all directors refused to realise and considered the ideas to be infantile (RadioWroclawKultura interview). 'Those people are completely apart from society. They live and they act like in the play 'Them' by Witkacy. No dialogue, dummy artificial contact. Pure form of infantile arrogance. (Mieszkowski. Dorota Wodecka, 1.09.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza). It was difficult or even impossible to react to Morawski's words. He does not talk in public with actors or spectators. He refuses to meet Mieszkowski in a TV debate, and because of that Mieszkowski was called off. Mieszkowski replied that this is not democratic.

Nowadays, negative comments are being removed from the Polish Theatre website. Under those circumstances actors and spectators started to react to Morawski's behaviours. Spectators organised the first protest. On the September 23, 'The Spectators of The Polish Theatre in Wroclaw' group walked on the stage with the black tape on their mouths, in the same way as the actors had done. In their hands they had the text 'I'm with The T[Pl' (TP[l – The Polish Theatre logo).

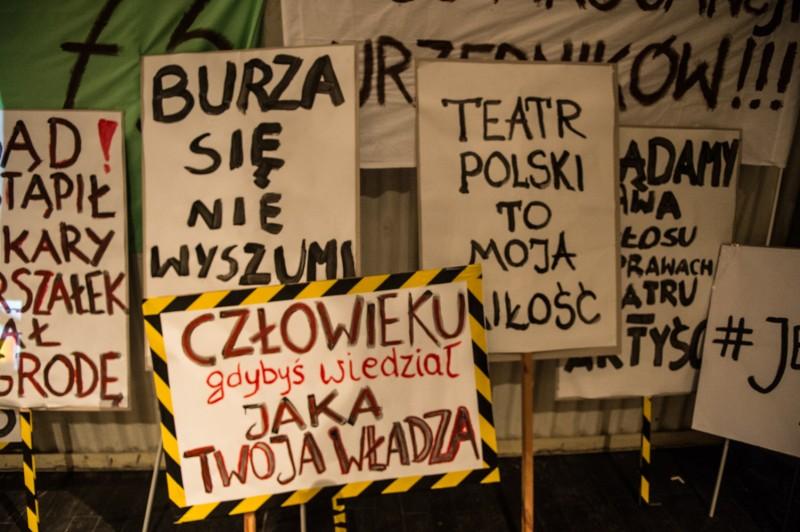

The war is on. The discourse places Morawski in the group of uneducated, angry people. The language, which has been used in the written battle is simple and clear. Discursive battle includes verbal and nonverbal communication. The first online petition has been written and shared online, demanding the resignation of Morawski. Another petition was written and shared, demanding to dismiss the Marshal Office, because the Marshal Office did not dismiss Morawski. Simultaneously to the petition, actors and spectators perform in the Marshal Office.

The protest entered the offline public space immediately after it started. As it was mentioned, Morawski was not accepted from the beginning. When he arrived to Wroclaw, actors went to the railway station to offer him a return ticket.

People were manifesting in the theatre and in the streets of Wrocław. Covered mouths were used several times. The language, which was being used by actors and spectators, is not only strong and simple, but also as poetic and emotional as the art it defends.

Polish artists started to publish their Facebook declaration that they are with The Polish Theatre. On the January 6, 2017 Marta Frej made a drawing, a joke of Morawski that said: 'I never was a beau, that's why I always wanted to play satrap' (the joke refers to roles that Morawski usually plays and is best known for as an actor – the boring, simple man).

Protest entered important city locations. In June 2016 The Polish Theatre Spectators organised the event 'Culture under threat' in NH cinema (known for New Horizons Film Festival). What is more, protests started to be broadcast all over the country not only by online media, but also by radio, printed press, and TV (including TVN24 with 1,16mln viewers).

What next?

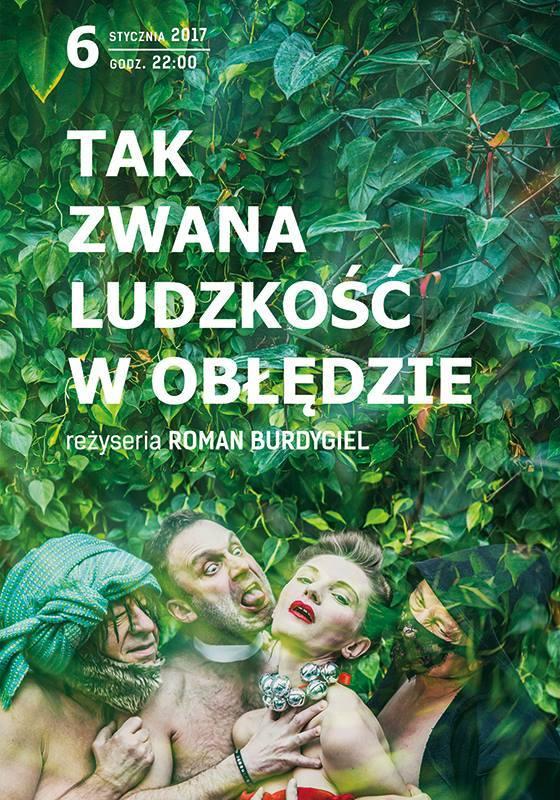

On January 6, 2017 the first premiere of Underground Theatre 'The so-called humanity in madness' [Tak zwana ludzkość w obłędzie] took place. It was in Capitol, the music theatre in Wrocław. Capitol invited The Polish Theatre and the spectators to use Capitol's space in order to proclaim The Polish Theatre rights. The tickets for the event was 1 PLN, which is about 0,25 Euro. The performance was also broadcast live on the 'Theatre in the underground' Facebook page. (Magda Piekarska, 7.01.2017, Gazeta Wyborcza). Capitol already supported The Polish Theatre in the past. During the New Year's Eve celebration, Capitol gave the performance on the Market Square of Wrocław. They came on the stage with mouths covered in black tape. After that, they sang 'Let the sunshine' (Polski Theatre in the Underground FACEBOOK, 1.01.2017).

It is not known what will happen with The Polish Theatre, but on their website they write that they will keep on fighting: 'We will fight. Morawski wants to abolish us, as he is afraid of us. He knows, that we will not give ground. Nor will the spectators. This battle for theatre is happening for the first time in Poland. (Michal Opainski for Newsweek Polska, in my translation). What is going to happen with Krzysztof Mieszkowski is also unclear, but it looks like he is fighting for democracy. 'In the name of the team, I want to say thank you to people all over the country. Do not be afraid of publicizing all immoral, harmful government attempts.' (Krzysztof Mieszkowski interviewed bt Dorota Wodecka, 1.09.2016, Gazeta Wyborcza, in my translation).

References

Aronson, E. (1997). Człowiek istota społeczna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Blommaert, J. (2005) Discourse. A critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Chlasta-Dzięciołowska M., (2015, December 15). Oni w teatrze. [Blog].

European Parliament News. (2016, September 13). MEPs urge Polish government to solve consitutional crisis. [Database]. REF. : 20160909STO41738.

Golgota Picnic. (2015, March 15). Golgota Picnic con subtítulos (VOSTFR-POLSKY). [Video file].

Kaszuwara P., (Kaszuwara). (2016, December 22). Awantura i przepychanki w Teatrze Polskim. [Radio broadcast]. Wrocław: RAM Radio.

Kościelna, J., Hamburger, M. (Kościelna). (2014, June 24). Pokaz Golgota Picnic i protest pod teatrem. [Radio bradcast]. Wrocław: Wrocław Kultura Radio

Lempert M. Siverstein M., (2012). Creatures of Politics. Media, Message, and the American Presidency. Indiana: University Press.

Ludzie Teatru. (2012, April 7). Ewa Skibińska czyta list "teatr nie jest produktem/widz nie jest klientem". [Video file].

Maly, I. (2016). New media, new resistance and mass media. A digital ethnographic analysis of the Hart – Boven – Hard movement in Belgium. In Papaioannou, T.: Media Representations of Anti-Austerity Protests in the EU: Grievances, identity and agency. London: Routledge.

Martinich A.,P., & Sosa D., (Eds.). (2011). Analytic Philosophy: An Antology. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Matuszewska M. (2016, September 1). Milczący protest załogi pod Teatrem Polskim: Nam zabrano głos, Wy możecie mówić. Gazeta Wrocławska.

Matuszewska M., (2016, December 16). Strajk w Teatrze Polskim? Cezary Morawski: Koniec anarchii. Nie pozwolę, by ktoś działał wbrew prawu. Gazeta Wrocławska.

Majewska K. (2015, November 23). Jelinek wydelikacona jak należy (Śmierć i dziewczyna). [Review]. Retrived from: http://www.teatralia.com.pl/jelinek-wydelikacona-jak-nalezy-smierc-dziew...

OZZIP. (2016, December 15). Antyzwiązkowe represje w Teatrze Polskim we Wrocławiu. [Data base].

Pelczar, I., (Pelczar). (2015, July 15). W Paryżu, Rio, Tokio i Pekinie chcą teatru z Wrocławia. [Radio broadcast]. Wrocław: Wrocław Kultura Radio.

Petycjeonline.com. Online petitions [Data base].

Piekarska M. (2016, November 29). Juliette Binoche do marszałka Przybylskiego: Co z tym Polskim? Gazeta Wyborcza.

Piekarska, M., Szymański W. (2016, December 17). Teatr Polski. Dyrektor bliżej wyjścia, czy to koniec Morawskiego? Gazeta Wrocławska.

Salon24 Blog. (2015, November 23). Dziady Mickiewicza a dziadostwo w TVPinfo. [Blog].

Szlendak T., Kozłowski T., (2008). Naga małpa przed telewizorem: popkultura w świetle psychologii ewolucyjnej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne.

Talik, M. (2014, June 27). Protesty przed „Golgota Picnic” w Teatrze Polskim. Gazeta Wyborcza.

The Editors (2016, September 15). Linguistic landscapes. Netherlands: Diggit Magazine.

The Polski Theatre. (2014, October 22). Holzfällen. 579 premiere of The Polski Theatre in Wrocław. Wrocław: T[pl.

Urbaniak, M. (2016, August 26). Perła rzucona przed wieprze. [Blog].

Wodecka, D. (2016, September 1). Teatr Polski we Wrocławiu. Zamach na teatr i demokrację. [Interview]. Gazeta Wyborcza.