The algorithmic populism of Alice Weidel

Technical developments and the growth of social media have caused politicians to start using social media as a tool for their political campaigns. This is also the case for Alice Weidel: the leader of the AfD. In this article, the algorithmic populism of Alice Weidel is analyzed.

Nationalist populism

“Populism is a frame that distinguishes ‘the people’ from the elite and ‘the people’ " (Maly, 2016: 11). Politicians who mobilize that frame, usually target ‘the elite' and claim to articulate 'the voice of the people'. Alice Weidel mobilizes this populist frame and fills it with German nationalism. Her voice is the voice of 'all Germans'.

The two tweets below show a thankful but dry Weidel. She celebrates that AfD gained more votes in the 2017 elections and thanks the people for their trust in AfD’s work. Even though AfD only managed to convince 13% of the population, she thanks the whole of Germany.

The lower tweets says: "Thank you so much to all the AfD-voters who made this result possible through devotion, courage and passion!". It is a little less formal than the top tweet, as she uses the heart emoji to express her love for all the people throughout Germany that voted for AfD. The picture shows a huge group of German people holding their flag, and the text 'Danke Deutschland' thanks them for their votes. You can even see one German national flag featuring the coat of arms (the one with the eagle), which can be read as celebrating a glorious, historic and weaponized Germany. At the moment of the elections, this was Weidel's Twitter header for quite a while, which shows the importance it has for her. Every time you opened her Twitter page, you saw this picture of the German people and her thanking them, acting as their leader.

Both tweets, in combination with the picture, create a very specific populist message: 'the people' are a national people. Whereas, AfD, and Weidel in particular, are communicated as their‘ voice’.

Algorithmic populism and the digital people

On Twitter and Facebook, Weidel's followers or digitalised fans, function as ‘the people’ she claims to represent. What's interesting, is that these followers are not a homogenic mass. When you scroll through her Twitter followers, you see a huge group of people from different countries and cultural backgrounds. A lot of them seem to support Weidel, but you can also find accounts that oppose or even study her (like L'observatoir du populisme in the screenshot below). Most of her followers present themselves as being right wing in their Twitter bios and general accounts, as seen in the picture below.

Besides this group, there is also a group of what we can call algorithmic activists (who use fake profiles or egg-profiles) and so-called bots, that haunt the Twitter sphere. Some of these activist profiles and bots don’t have a picture or bio. They have a generic name and no (or very few) tweets. Nevertheless, they can play a big role in online politics, as they can highly increase the amount of followers a politician has and thus help to create the message that Weidel is actually supported by the German people.

A big group of Weidel's followers fit this 'algorithimic activists-profile'. They look like algorithmically managed empty accounts. Their only reason to exist seems to be to increase the amount of followers, retweets, and likes of Weidel.

This type of activism not only helps to construct the idea of popular support, it also creates more publicity. Such activism is typical for a new type of populism, which Maly (2018) calls algorithmic populism. Algorithmic populism aims at virality and in trying to reach this virality one not only relies on human supporters, but also on these bots and algorithmic individuals. These bots are often bought online, set up by people working on campaigns or used by activists.

Bots are playing an ever-increasing role within contemporary politics, and Weidel acknowledges this. In October 2016, Weidel claimed that "of course, we are considering which tools in the social media area make sense for our public relations work. These include analysis or utility programs that could make daily work easier. However, we will of course not use social bots that post automated messages on third party sites on behalf of the AfD or something similar." (AfD, 2016). This was after other reports on the AfD's election campaign claimed that they were in fact going to use bots (2016).

Bots, eggs and the people

What's important to note, is that without technical solutions, it is very hard to prove whether an account is a bot, or just an inactive Twitter account. There are some websites and online auditive services that claim to be able to show you whether a Twitter account is a bot (like Botometer) or that can help you find out how many of an account's followers are 'real' (like Twitter Audit). However, these websites are not 100% accurate. Therefore, it is very difficult to prove exactly how many of an account's followers are real and which exact followers are bots.

That being said, generally speaking, egg-profiles are quite indicative of activist controlled accounts. Scrolling through Weidel's list of followers, there is a huge amount of inactive accounts that fit the profile of a badly set-up (non-disguised) activist accounts and/or bots. They do not have a profile picture or header, zero tweets and generally about zero to ten followers. All they do is follow a few accounts, which is often the only reason they exist.

Below, you can see two of the egg-accounts that follow Weidel. The two accounts fit the ‘activist profile’ perfectly. They are very inactive in every Twitter aspect and seem to only exist to add to Weidel’s follower count and in that way amplify her message. The top account is clearly set up to be German, as ‘Vor Und Zuname’ is German for ‘first and last name’. That is also the only information that is on this account. For the second account, it is not even clear where the account comes from (or was possibly bought from). Both accounts haven't tweeted anything.

These are just two of Weidel’s followers that were picked from the list of egg accounts within seconds. As mentioned above, it is hard to prove if these accounts are bots or if they are just highly inactive, but the amount of such 'accounts' that follow her can still be seen as somewhat suspicious.

Populism and online social movements

This craving for virality within algorithmic populism shows the importance of visible numerical support for populists. Their goal is to construct the perception that they articulate ‘the voice of the people’. The populist discourse only works if it generates uptake; if it mobilizes 'the people'. It is therefore always used in the hopes of addressing a certain group of people, who by linking, sharing or visually supporting the populist, help to legitimize the idea that the populist truly has popular support.

Social media have become important political battlefields. Numbers are politically important, and as a result, a new type of activism has emerged: algorithmic activism. In the digital age, populists need some type of (grassroots or astroturf) support group to create the image of popular support. It is important to have an online audience and an online social support group or even a social movement.

These online social movements have similar goals to the old social movements. They “are the producers of new values and goals around which the institutions of society are transformed to represent these values by creating new norms to organize social life” (Castells, 2015: 8). What differs are the tools to get themselves and the voice they believe in out there.

One of those new important propaganda tools are memes. Memes are “cultural units that are distributed through copying, imitating, sharing, reworking”. Memes can be used as a form of online political propaganda and many extreme right wing activists in the US, The Netherlands, Italy, and Australia use them to stretch the overtone window. The irony that memes are associated with is now used in politics to make radical ideals seem more mainstream.

What's more, the fact that memes are made to go viral within the algorithmic ecology of social media lets them gain a bigger audience and again, get their ideals and voice spread. A third function of political memes is phatic, they can in this way make people curious or even create a group identity.

Reconquista Germanica: creating a meme-war

An example of a local online support movement for the AfD (and Alice Weidel) that uses memes as a political tool is Reconquista Germanica: the local German manifestation of the global New Right movement (Maly, 2018).

Reconquista Germancia has a Facebook page with almost 15.000 likes and followers (as of November 28th, 2017), a Twitter and a YouTube account. All these social media accounts share ridiculous pictures and memes revolving around the mainstream/establishment political parties (especially the CDD, SPD) and of course the AfD.

The Reconquista Germanica memes try to start a so-called meme-war: “warfare through trolling and memes is a necessary, inexpensive, and easy way to help destroy the appeal and morale of our common enemies.” (Bernstein, 2017). Their goal is to ridicule the CDD and SPD and shine a positive light on the AfD. By doing so, they are giving the AfD positive visibility through social media. They reproduce Weidel’s voice, help her go viral and create the perception of popular support.

The memes that are produced by Reconquista Germanica try to start a meme-war.

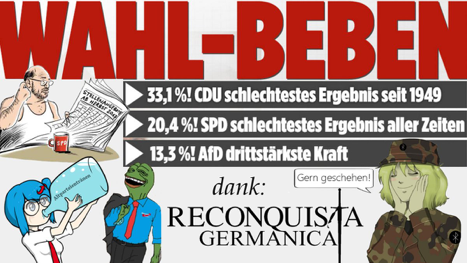

In the picture called ‘Wahl-beben' (“election earthquake”) shown below, the percentages the three main parties achieved in the recent German elections are shown. They make fun of the CDU and the SPD, saying that they both received the worst results in a long time, but they praise the AfD for being the third strongest party and say that RG is to thank for this. Weidel is depicted here as a manga cartoon. She looks like a nice character, yet also as a warrior, as she is wearing a soldier’s uniform. Other characters, such as Pepe the Frog – the famous alt-right meme – wearing an AfD uniform are also shown.

This online support movement and its meme war have even created offline mobilization power: "the power to activate your base and turn them into active participants in public life" (Tilly, 1978: 69). There have been members of RG that went outside to spread their ideals in real life, as seen in the picture below. They are holding posters, showing memes and carrying the German flag. Even the police can be seen in the background. The pictures that were taken (such as the one shown below) at these protests are also proudly displayed on their Facebook page.

Alice Weidel and the voice of the people

Online social movements and bots help to create the idea that AfD and Weidel are truly articulating the voice of the people. What's more, their actions trigger the algorithms that come into play for gaining popularity and spreading the voice of the AfD. The great amount of algorithmically constructed followers help Weidel to gain popularity.

For right wing parties, such as Weidel’s AfD, online support movements such as Reconquista Germanica also contribute to the construction of a populist image. Memes in particular have influence on spreading the voice and message of both Weidel and the AfD in general. The impact of social media is enormous and grows even more when it starts to intertwine with offline life and creates offline mobilization power. Maybe soon, meme-wars will not only be online wars.

References

AfD. (2016). AfD lehnt Einsatz von sogenannten social bots ab. Retrieved on November 30th, 2017.

Bernstein, J. (2017). This Man Helped Build The Trump Meme Army — Now He Wants To Reform It.

Castells, M. (2015). Networks of outrage and hope. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lempert, M. and Silverstein, M. (2012). Creatures of politics. Media, message and the American presidency. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Maly, I. (2016). Why Trump won. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Maly, I. (2018a). Nieuw Rechts. Berchem: Epo.

Maly, I. (2018b). Populism as a mediatized communicative relation: the birth of algorithmic populism. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 2013.

Maly, I. (2018c). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism. Diggit Magazine.

Richardson, G. W. (2017). Social Media and Politics: A New Way to Participate in the Political Process. California: Praeger.

Tilly, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. Michigan: University of Michigan.