Behind the Curtain: “1984”’s Aesthetics of Immediacy

The TV ad “1984,” directed by Blade Runner’s Ridley Scott, introduced the Apple Macintosh PC to the world for the first time. Referencing Orwell's 1984, its ostensible message is rather on the nose. Yet, if we take a closer look at the aesthetics of this ad with a duration of only 45 seconds, we see that many other intertextual links can be made; some of which not necessarily intended. In this article, I point out some of these intertexts—from the aesthetics of fascism to Plato to The Truman Show—and discuss what I call the video’s ‘aesthetics of immediacy.'

The 1984 ad

“1984” opens with an extreme long shot of a line of male workers marching through a long tunnel in tandem, monitored by a line of TV-screens on the wall. The setting is industrial and dystopian, its color scheme made up of blues and greys, the air hazy with smog—evocative of the opening scenes of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, although we also recognize Scott’s style from Alien and Bladerunner. The men are pale, their heads shaven, with grey uniforms that make them look like prisoners. They enter a monumental hall and march towards an enormous screen; a hybrid between a movie theatre screen and a computer screen with code displayed along the borders. They are seated on benches facing it. On the screen, a middle aged 'Big Brother' figure performs a speech. The top and bottom of his face are cut off by the frame, his words appear onscreen in white typeface. We hear his voice, belting out Orwellian ‘Newspeak’ about information, purification, a “garden of pure ideology” and the “Unification of Thoughts.”

In a flash, we see a female athlete running towards the screen, sporting a large sledgehammer. With her short blonde hair, red shorts and shoes, and white sleeveless top, she stands out from the greyness of the rest. An alarm sound announces her approach; she is chased by four helmeted cops. Framed by huge marble columns, we now see the woman in full, guards on her heels. We can even discern the drawing on her top: it is the famous Apple logo, an apple and keyboard. She makes a final sprint and cries out as she forcefully releases the hammer, which hits the screen in slow motion. As the tyrant shouts “WE SHALL PREVAIL,” the screen explodes with a flash and lots of smoke. We see the shocked audience as the white light washes over them, mouths agape in astonishment. We hear the sound of the wind, as if an outside reality is unlocked. Black letters appear onscreen as a male voice says: “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you will see why 1984 won't be like “1984”." Fade to black; the Apple logo appears.

Technopanic meets Fascinating Fascism

So what was Apple trying to say? In a not-so-subtle manner, the ad is using Cold War imagery associated with the Soviet Union and displacing it onto rival company IBM (‘Big Blue’), which then dominated the computer market. It does so by speaking to the prevalent theme of technophobia: for instance, through images of disembodiment. In one shot, the prisoners’ heads are cut off from the frame, as is the technologically mediated 'talking head' which controls the body of the collective (Stein, 1997). The ‘technopanic’ addressed here is dehumanization: as computers become more like us, as extensions of the human mind, we become like them and our bodies will become obsolete. The marching workers are automatons, their bodies move mechanically as if they have been programmed by the droning voice, incapable of thinking for themselves.

With its excessive aesthetics, monumental setting, and sublimely endless line of workers, the ad’s representation of the world of automatons can be characterized in terms of the aesthetics of fascism. According to Susan Sontag in her essay "Fascinating Fascism,"

Fascist aesthetics … flow from (and justify) a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behavior, extravagant effort, and the endurance of pain; they endorse …. egomania and servitude. The relations of domination and enslavement take the form of a characteristic pageantry: the massing of groups of people; the turning of people into things; the multiplication or replication of things; and the grouping of people/things around an all-powerful, hypnotic leader-figure or force. (1980, 91)[1]

The prison-world depicted in “1984” ticks all these boxes—unsurprisingly perhaps, since it is supposed to be representing a totalitarian dystopia.

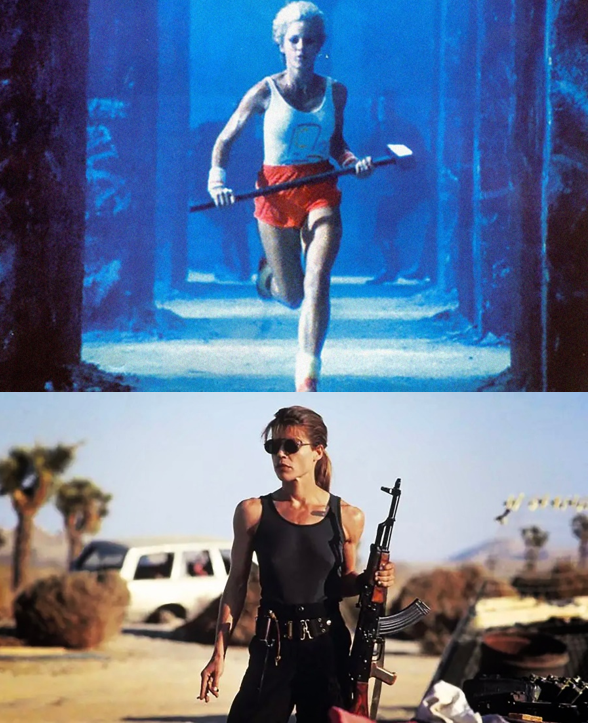

However, it is not just the communist-fascist world of uniform dreariness that taps into the forms and style of fascism. When this world is subsequently scattered by the athlete, it is substituted by the utopian aesthetics of physical perfection and eroticism. For Sontag, “[t]he fascist ideal is to transform sexual energy into a “spiritual” force, for the benefit of the community” (1980, 93). The trope of the female warrior thus also aligns with the aesthetics of fascism (not the communist kind, but the Nazi kind). It is therefore no coincidence that a woman was cast as this liberating force. Sarah R. Stein (1997) compares the female athlete in the ad with Sarah Connor, John’s mother in the Terminator franchise (another war of man against machine), of whom she writes that “sexuality was configured as a life force she could call upon in her warrior role.” Both are lone figures, entrusted with a dangerous and heroic task upon which the survival of mankind depends.

With the explosion of the screen, one spell is broken and another one is cast, one ideology exchanged for another. Alienation is followed by re-enchantment.

My point here is not that this is a ‘fascist’ commercial, but rather that its use of fascist styles and themes reminds us that certain National Socialist ideas, such as “the ideal of life as art, the cult of beauty, the fetishism of courage, the dissolution of alienation in ecstatic feelings of community…, ” have not died out (Sontag, 1980, 96). With the explosion of the screen, one spell is broken and another one is cast, one ideology exchanged for another. Alienation is followed by re-enchantment.

The athlete in “1984” and Sarah Connor in The Terminator (Cameron, 1984)

But what then is this ideology? Notably, the aforementioned technopanic of dehumanization only pertains to IBM’s older computers. The heroic female runner has full command of her body which cannot be controlled or contained. She acts as a stand-in for the new PC, the object of desire that is colorful and exciting. The Macintosh PC introduces creativity, originality, and individuality, underlining the “personal” in personal computing (which we see repeated in their “Think Different.” campaign from 1997). How can you possibly say no to that? It is an ideology disguised as freedom from ideology. We could call it capitalism, like Mark Fisher (2020) does, and the take home message would be: capitalism is the opposite of boring, it is about desire.

Through its products and especially its marketing, aided by all technological advancements introduced since this commercial, Apple aimed at reenchanting the world by restoring color and life to it, 'filling it in'. Rather than a representation of our world, they offered a whole new world. In this respect it is fitting that the Apple logo, an apple with a bite out of it, evokes the Old Testament's Garden of Eden. Like Eve biting the apple from the Tree of Knowledge, the female athlete’s bold act can be seen as an original sin that leads to both aesthetic pleasure and knowledge. The humanization and personalization of the computer as a counterpart to dehumanization—a fear first carefully instilled by the commercial itself—harbors a promise of emancipation, a celebration of self-expression and freedom from monopolistic control.

Pay no Attention to the Men Behind the Curtain

So now we have seen what's there, let's also pay attention to what is not. You may have noticed that one thing conspicuously absent from the commercial is the actual product, the Macintosh PC itself—reminding me of how in the teaser trailer for the original Jurassic Park (Spielberg, 1993) no actual dinosaurs were to be seen, which only added to the collective, hyped-up anticipation. This is “advertising spin[ning] a web of associations around a commodity while obscuring the material reality in which that commodity is produced and consumed,” as Niels Niessen puts it in an essay about the marketing campaigns for the iPhone (Niessen, 2021). Throughout its history, Niessen shows, Apple has consistently sold a belief in “a world made better by design”: technology becomes quite literally a second nature, a doubling of reality, the whole world integrated into one technological "iDream." Like Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, this dream world necessarily disconnects itself from, and erases the traces of, historical materiality,[2] so it is fitting that the ad erases the material reality of the product itself.

When I first saw the “1984” ad, my go-to association was not Orwell but Plato’s cave allegory. In a famous dialogue between Socrates and Plato’s brother Glaucon in book VII of The Republic, they imagine a group of prisoners chained together inside an underground cave. Behind them is a fire; between them and the fire are moving puppets and objects above a low wall. Since they can't move, they can only see the cave wall in front of them which shows the projected objects in the form of shadows. Unfamiliar with a world beyond, they mistake the shadows for the real things. Socrates and Glaucon wonder what would happen if a prisoner would be forced to leave. Such a prisoner would at first be blinded by the light of the sun (and this is probably the moment in “1984” that triggered my association; the way that the prisoners are flooded by white light when the screen is destroyed). Socrates and Glaucon allege that, would the—literally—enlightened prisoner go back to report on the real world to his cave fellows, they would likely kill him. They would prefer the comfort and safety of the world they know.[3]

Plato’s Cave Allegory. By 4edges - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

This idea of our manifest world being illusory and the possibility of accessing a truer, more ‘real’ world beyond it, is a popular trope beyond philosophy. In The Truman Show (Weir, 1998), insurance salesman Truman Burbank is the unknowing star of his own documentary reality TV show. The small town he lives in is in actuality a gigantic television studio set, everyone but him an actor paid by the production company—including his ‘mother’, ‘wife’, and ‘best friend.’ When Truman realizes his entire life has been staged, he finds a way to escape the studio. When his boat bumps up against the literal borders of his world, Truman, unlike Plato’s prisoners, chooses freedom over security.

Truman leaving the set. Still from The Truman Show (Weir, 1998)

The Matrix (Wachowski & Wachowski, 1999) has a similar dual worlds structure, but here the ‘real’ world is a postapocalyptic wasteland after humans have lost the war from AI (a reversal from “1984”). The world people purportedly inhabit is the Matrix, a computer-generated simulation of pre-war reality. Like “1984,” The Matrix uses different color schemes to distinguish reality-levels (the ‘real’ world of 2199 rendered in cold, bluish, desaturated colors; the computer-generated world in a greenish, more saturated tonality). When hacker Neo discovers this dual structure of existence, he decides to take the red pill. Like Truman, Neo trades in his comfortable existence for knowledge of the truth.

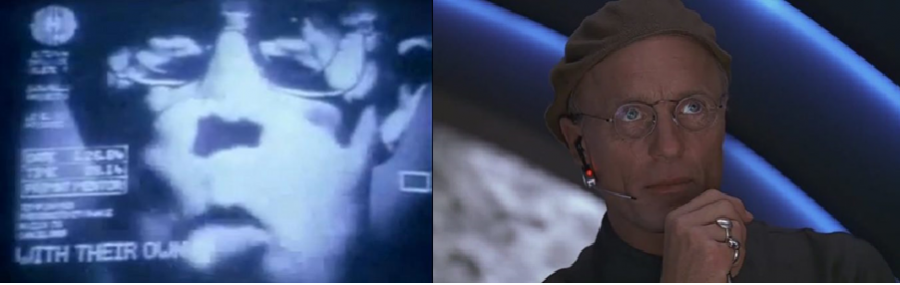

Similarly, in “1984,” the moment the hammer shatters the screen, a 'real world' is revealed behind the illusory one, as when the man behind the curtain is exposed in The Wizard of Oz (Baum, 1939). Whereas the spell of IBM’s onscreen Big Brother, like that of the wizard, is broken when the hammer hits and unmasks him as a representation/a fake, Apple itself pretends to offer us not just another representation, but unmediated access to the world.

‘Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!’ Still from The Wizard of Oz (Baum, 1939)

Rancière wrote that the TV screen “suppresses the mimetic gap and ... thus realizes, in its own way, the new art’s [cinema's] panaesthetic project of immediate sensible presence” (2006, 18-19), which is exactly what happens here with the computer screen. Of course, what is revealed is not ‘reality,’ but merely another mediation: unmediated access to the world itself is an illusion. Capable of decreasing the distance between reality and its representation, digital technologies run the risk of reducing the world to its technological representations.

“1984” in 2024: The Walled Garden

Unlike the many apocalyptic man versus machine films of the same era, the “1984” ad literally saw a bright future for humanity. Did that future materialize? At the very least, we can say that 2024 is not exactly like Apple's "1984." Rather than being mesmerized by one screen and forced to sit still, today, we each have our own little portals to tap into this second world every minute of the day: "If you think a crowd of people staring at one screen is bad, wait until you have created a world in which billions of people stare at their own screens even while walking, driving, eating in the company of friends—all of them eternally elsewhere" (Solnit, 2014). This proliferation of screens constitutes a hypermediated immediacy already foreshadowed in “1984”.

However, watching this commercial in the age of Big Tech and ubiquitous surveillance, our enthusiasm about the promise of freedom and emancipation through technology has been somewhat tempered. The current media landscape has not turned out as a unified, totalitarian world that’s forced upon us from outside. Instead, it offers us a freely chosen dispersal of worlds with a decentralized, networked structure, a global information economy that knows no beyond.

Are we passive bystanders with respect to the ugliness happening behind the scenes, voluntarily distracted by colorful images and shiny gadgets, happily trading in some of our freedom for the comfort of Apple's attractions?

In the 2015 documentary about Apple’s front man, Alex Gibney states that Jobs “offered us freedom, but only within a closed garden to which he held the key”. Ironically, this makes him a bit like Truman’s TV director, or the dictator in his own commercial. There’s a good chance that the reader encountered a parody of “1984” in Fortnite in 2020, protesting that gaming platform’s ban from the App Store and addressing Apple as part of “the Platform Unification Directives” who hold a monopoly over a closed-off app ecosystem. Has Apple become the tyrant it claimed to defeat?

Talking Heads in “1984” and The Truman Show (Weir, 1998).

While we seem to be a lot more active than "1984"'s workers (or the spectators in Plato’s cave) and while we have free choice of a seemingly unlimited range of diversions, one can wonder about the reach of our vision and agency in Apple’s theatre. Are we passive bystanders with respect to the ugliness happening behind the scenes, voluntarily distracted by colorful pictures and shiny gadgets, happily trading in some of our freedom for comfort? Apple's world may not be a garden of “Pure Ideology” or a garden of Eden, but it has borders nevertheless.

References

Mark Fisher, What is Postcapitalism? Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures. Ed. Matt Colquhoun. Repeater Books, 2020.

Alex Gibney, Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine. Documentary, 2015.

Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture. Advertising & Society Quarterly 22.2, 2021. Web.

Plato, Republic, Book VII. Ebook Project Gutenberg, 1998. Web.

Jacques Rancière, Film Fables, trans. Emiliano Battista. New York: Bloomsbury, 2006.

Rebecca Solnit, Poison Apples. Harper’s Magazine, Dec 2014. Web.

Susan Sontag, Fascinating Fascism. Under the Sign of Saturn. New York, 1980, 73-105.

Sarah R. Stein, The “1984” Macintosh Ad. From: Redefining the Human in the Age of the Computer: Popular Discourses, 1984 to the Present. University of Iowa, 1997. Web.

[1] It is important to note that for Sontag, fascist aesthetics is not confined to propaganda or to art commissioned by fascist governments: besides Leni Riefenstahl Triumph des Willens, she mentions Disney’s Fantasia, Busby Berkeley’s The Gang’s All Here, and Kubric’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1980, 91).

[2] In the case of the present-day company Apple, what is obscured from view is capitalist reality and its inequalities: the mining of the earth and exploitation of labor (Apple's products are made in China under dreadful working conditions). In addition, Apple supports the data mining practices of Google and Facebook and tracks its users (Niessen, 2021).

[3] Plato's allegory was meant as a thought experiment about epistemology, to allegorize the difference between the phenomena as empirically presented to our senses and the realm Ideas or Forms, the eternal and unchanging Ideas of which these phenomena are but weak copies.