How ContraPoints commands the YouTube Stage

In this essay, I examine ContraPoints as a female public intellectual in the context of strategies of self-representation in the attention economy. How to be a public intellectual in a media landscape marked by ‘post-truth’ sentiments, in which we have to count on algorithms to filter out information for us, and in which the expertise and authority of once-trusted sources of information are deeply questioned?

How ContraPoints is competing with the Kardashians

Natalie Wynn aka ContraPoints has adapted unique strategies to cope with these problems and challenges of making sure her voice is heard in an attention economy. Wynn is a 30-year-old transgender woman who lives in Baltimore, Maryland. She was getting her PhD in Philosophy and teaching at Northwestern University, Illinois. That was a few years ago, and now she earns a lot of money with her own YouTube channel. In this article, I consider her position as a female public intellectual in increasingly hybrid, interconnected and plural public spheres. Here, I will be mostly discussing the form that her engagement takes, rather than dwelling at length on the message or content of her videos.

According to Edward Said’s Representations of the Intellectual (1996), the public intellectual has “a faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as well as for, a public; [She] confronts orthodoxy and dogma, representing people and issues that are routinely forgotten or swept under the rug”. Said sees the public role of the intellectual as outsider, amateur, and disturber of the status quo, who is committed to democracy and universal human rights.

Of course, the arena of this intellectual has changed considerably since then. The intellectual of Jürgen Habermas’ day had a smaller range of media to choose from, and even compared to 1996 (when Said’s essay came out), the public sphere has become more complex. In fact, it is no longer correct to speak of a public sphere in the singular: today’s e-platforms shape highly complex and flexible public spheres and highly specific, algorithmically configured publics. Democracy and universal rights are fiercely and often worryingly debated in online public spheres, considered by some a ‘free marketplace of ideas’.

Whereas earlier historical periods faced the challenge of a scarcity of information, today we have an excess of it to combat. And while information is not scarce, other things are: cognitive effort, energy, time, attentional resources. The Economy of Attention is a principle that originated in marketing, and that describes how attention becomes currency. In today’s media sphere, we assign value to a thing according to its capacity to attract views, clicks, likes, and shares (‘draw eyeballs'). What is new compared to Said’s time, is the algorithmic agency that determines many of the intellectuals online interactions and transactions. Contrary to the lecture room, newspaper or TV talkshow, online 'stages' have platform structures that do not correspond to the more traditional ones. It's the algorithmic dimension that accounts for the dissipation of 'publics'. This shapes a crucially different 'public' environment from that of the previous generation.

Attention is quantified and monetized in a world saturated with media. Much of this revolves around self-representation, around the cult of personality over message; around clickbait titles and the role of extreme emotions. The increasing commercialization and personalization of political discussion in the public spheres is exacerbated by a crisis of expertise, a culture of doubt and skepticism. Since the 1960s, academics, traditional news outlets, and scientific research alike are faced with an erosion of trust from the public.

The informed views of the public intellectual are in competition for our time and energy with cat videos, fake news, Game of Thrones memes, political discussion forums, travel pics on Instagram, interior design tips on Pinterest, fitspiration videos, Netflix, and of course The Kardashians.

Intellectuals today have to enter this arena. The informed views of the public intellectual are in competition for our time and energy with cat videos, fake news, Game of Thrones memes, political discussion forums, travel pics on Instagram, interior design tips on Pinterest, fitspiration videos, Netflix, and of course The Kardashians. How to carve out a position for yourself as an outsider who is still ‘connected’ enough to be taken up in these algorithmic public spheres? How to convince an audience outside your bubble of the validity of your viewpoints? Can you be too public to be an intellectual, or too much of an intellectual to be taken up by the public? Or has this question lost its meaning in a public sphere that has become not only more complex, but also multiplex - with very many and very different 'publics' available in a new media economy?

The Oscar Wilde of YouTube

Wynn maintains a firm distinction between herself as a creator and ContraPoints as her web personality. Then within her YouTube videos, she plays multiple characters, often voicing diametrically opposed views, who enter into dialogue with each other. These alter egos can be considered heteronyms, in the literary tradition of inventing ‘characters’ who display different traits of the writers identity and have their own unique styles. The Portuguese writer and poet Fernando Pessoa is known to have had over 70 of such heteronyms.

ContraPoints’ alter egos include the gender non binary drag queen Baltimore Maryland, a character called The Doctor who comes in when scientific topics need to be elucidated, Lady Foppington, make-up artist Tiffany Tumbles, and my favorite: Tabby, an anarcho-communist trans cat-girl who wears an ANTIFA patch and wields a baseball bat to smash capitalism. There is also Fritz the fascist, who later has to transition along with Wynn, into Freya the fascist. These heteronyms allow Wynn to give her videos a dialogical structure, and to voice viewpoints that prevail in today's public spheres, without embracing them or critiquing them from the outset.

Odile Heynders (2016) has underlined the importance of performativity in understanding the impact of public intellectuals. This includes attention to dramaturgical devices: from stage-setting and genre to rhetorical deviced contributing to the persuasiveness of the arguments. In her forthcoming chapter on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2020), Heynders takes the concept of the ‘stage’ (Baert & Morgan 2017) as an analytical tool to study how the public intellectual performs her life on multiple stages, which she understands as including rhetorical strategies and literary devices, written texts and public performances. Here, we must also differentiate between platforms, as the affordances of (micro-)blogging are clearly of a different nature than those of YouTube or Instagram, as the case of ContraPoints drives home.

Wynn uses YouTube as her stage in an almost literal, material way. Everything you see and hear in het videos is well thought out and meticulously curated. She designs the intricate sets herself, she specifies dramatic lighting schemes in her scripts, and assembles elaborate costumes. The videos include original music by the composer Zoë Blade. ContraPoints herself is often theatrically attired. She looks extravagant, constantly makes jokes about herself, talks fast and with a soft voice and is extremely eloquent yet sometimes foulmouthed. She understands the role of emotional appeal in the success of many far right and alt-right movements around the world, and she contests that vision with something at least as aesthetic and visceral. Her aesthetic slant has brought her the nickname ‘YouTube’s Oscar Wilde’.

Wynn sometimes revisits earlier videos to talk to her earlier self. In “Debating the Alt-Right,” ‘live viewer responses’ scroll across the lower third of the screen, extending the dialogue between ContraPoints’ roles as she creates dozens of fake viewer accounts who talk back to her on-screen characters. Nicole Morse (2018) puts ContraPoints videos in the emergent category of “selfie aesthetics”, whereby the self is presented as layered, and as evolving over time. In this case, the effect is particularly powerful as fans who started watching her videos from the beginning are also witnessing Natalie’s transition from male to female.

Converting the Alt-right?

In the video “Why I Quit Academia,” Wynn explains how she came to this dramatic life decision. She says here: “Rightwing dingdongs like to paint academia as some sort of leftist Madrasa where Marxist-feminism is the only permissible worldview. This is an exaggeration, but it’s not THAT much of an exaggeration.” She continues to relate how she was once in an advanced political philosophy seminar with some other grad students, where they had to discuss a book by libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick. She says:

“None of us were able to mount any kind of plausible argument against Nozick. Not because Nozick is correct, but because we as a group had no experience arguing with anything that far to the right... we’d all cut our teeth dissecting these little squabbles between Rawles and Habermas, and we had no experience arguing against anything as far-right as the political views that most Americans actually hold” (2016).

So she turned to YouTube, her primary channel of expression or ‘stage’. At the time of writing, she has 739K subscribers and over 38.5 million total views.[1] Her channel is financed through the crowdfunding platform Patreon, where ContraPoints is among the top 20 creators. When her 2018 video about incels reached over one million views, The New Yorker released a profile of Wynn’s channel, calling her amongst other things “one of the few leftists anywhere who can be nuanced without being boring”.

The main goal of the channel ContraPoints is to counter rightwing political argumentation, which runs rampant on YouTube. Wynn’s target audience are angry young white men who sympathize with the alt-right. In her videos, Wynn uses philosophy, sociology, and personal experience to explain left-wing ideas and theories, and to counter common conservative, classical liberal, alt-right, and fascist viewpoints. Whereas many left-wing public figures put a lot of energy into ridiculing the right and refuse to enter into a debate with its proponents, ContraPoints tries to understand the mindset of young men at risk of radicalizing (even saying she used to be one of them), so that she can speak to them at their level, informed by her education. And this works. Many testimonials can be found of young men who thank her for showing them alternative perspectives.

She emphasizes that persuasion is not reducible to reason—that the best arguments, on their own, do not always win. Cultural authority is assigned to Wynn from viewers across the political spectrum, on the basis of her media performances and unique ways of packaging her message. Form and content are deeply entangled, and she demonstrates an understanding of the importance of aesthetics. In an interview with Vice, she says: “People don’t believe because of facts and evidence. They believe things because they’re part of a story they’re telling themselves. And I guess what I’m doing is understanding those stories and understanding psychologically why are these stories being told.”

Framed on the Twitter Stage

ContraPoints has an astute sense of, or as Habermas (2009) would say, “an avant-gardistic instinct” for relevance. She has a humorous rhetorical style and pays close attention to online culture, for instance in her analysis of fascists’ use of memes and coded symbols like the OK sign. In her critical videos about influential figures like Jordan Peterson and Ben Shapiro, she always gracefully acknowledges her opponents' valid points before debunking weak arguments and revealing the influence of a hidden far-right political agenda. She does this without being condescending to people with different epistemologies.

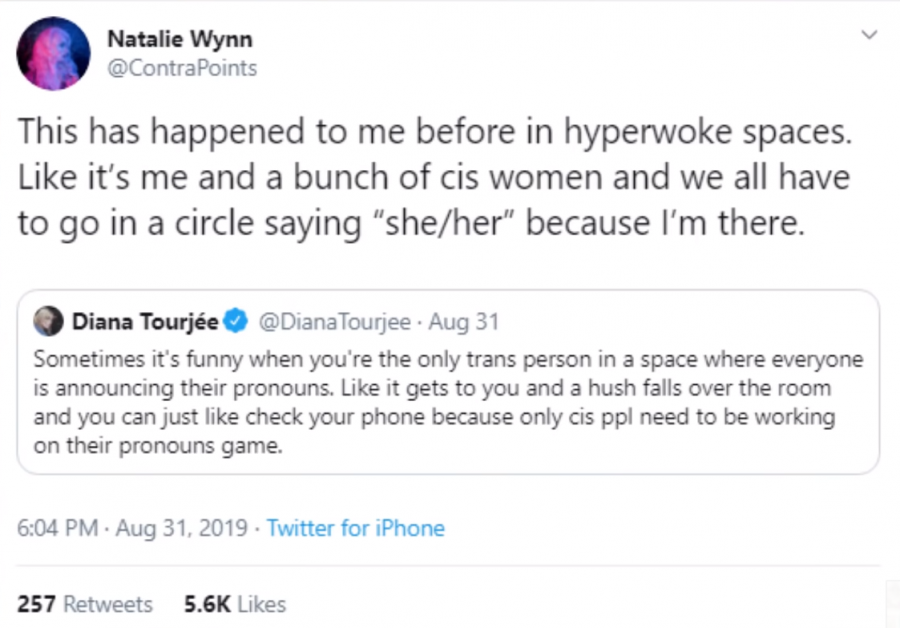

Following Baert & Morgan and Heynders, the public intellectual performance is carried out on multiple stages. Wynn also performs on the Twitter stage, but with less unanimously positive results. Recently, she was the center of a controversy involving nonbinary people —people who don’t identify as male or female, and who prefer to be referred to with “they”/“them” pronouns. Wynn expressed that she isn’t always a huge fan of having to specify her pronouns, as she would like to be perceived as a woman by default. As a binary trans person who identifies as a woman, having to make her preference for the use of ‘her’ and ‘she’ explicit in ‘woke’ companies makes her feel uncomfortable.

The backlash was so vicious that she temporarily went off Twitter (only to re-enter its stage weeks later). Little clashes like these seem almost inevitable for those who voice an opinion on issues that are of tension within the trans community. Pronouns are aan example of such a sensitive topic. As a Marxist-socialist, Wynn does not always subscribe to the liberal or ‘Tumblr-left’ opinions.

The Twitter stage is a good example of a platform that not only empowers but also restricts potential (self-) presentations. An obvious affordance that restricts is the 280-character limit, which does not allow for elaboration and nuance (and Twitter’s recent ‘thread’ feature forms a further restriction). Another form of restriction is caused by a certain ‘policing’ style of commenting, and the internal frictions and disagreement in the leftist echelons of Twitter. Twitter can turn against you at the drop of a hat. This is how a stage can become a frame, and I would propose to use ‘staging’ here as an act of performance and performativity on a chosen stage, while ‘being framed’ is a powerless, passive experience of having your performance interpreted by the audience in a certain way.

ContraPoints shows how to be a Female Public Intellectual in the Attention Economy

Wynn carefully curates and ‘stages’ her self-image in a world saturated with images vying for our attention, and take acts of representation and framing into their own hands through strategies like cutting and pasting, hypermediacy, and theatrical performance. Her strategy of self-presentation is one of being hypervisible, of multiplying the self, and presenting the self as quite literally in transition instead of fixed and unchanging. This sense of self-awareness, of taking control over every aspect of their image, makes her an inspiring cases of a female public intellectual for the selfie age.

[1] By the way, this practice of academics and critics like me listing the numerical popularity of their chosen case studies, and thus legitimizing them, is another example of how the attention economy works.

References

Baert, Patrick & Marcus Morgan. “A Performative Framework for the Study of Intellectuals”. European Journal for Social Theory, 2017, pp. 1-18

Habermas, Jürgen. Europe, The Faltering Project. Trans. Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.

Heynders, Odile. Writers as Public Intellectuals, Literature, Celebrity, Democracy, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Heynders, Odile. “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The Public Intellectual on Stage.” In Gibbons, Alison, & Elizabeth King. Reading the Contemporary Author, Ohio State University Press.Forthcoming 2020.

Morse, Nicole. Selfie Aesthetics: Form, Performance, and Transfeminist Politics in Self-Representational Art. Dissertation, U of Chicago, 2018.

Said, Edward. Representations of the Intellectual. The 1993 Reith Lectures. New York: Vintage, 1994.