Fandom of AKB48 Groups

AKB48 is a famous Japanese idol group. Members from the AKB48 fandom come from Japan and other Asian countries. This article provides an introduction to the roles of these fans of AKB48 and its sister groups.

Domestic and overseas increase of AKB48 groups

AKB48 is a Japanese idol group with more than 100 young female singers, organized in 2005 by chief producer Akimoto Yasushi. Between 2011 and 2012, AKB48 was ranked as one of the top 10 hit “products” in Japan (Kiuchi, 2017, p.31). The group was registered as the largest pop group by Guinness World Records in 2013 (Guinness, 2013). Moreover, AKB48 has many domestic and overseas sister groups.

The domestic groups are, for example, SKE48 (based in Sakae and launched in 2008), NMB48 (based in Namba and launched in 2010), HKT48 (based in Hakata and launched in 2011), and so on. The foreign sister groups include JKT48 in Jakarta (Indonesia) in 2011, BNK48 in Bangkok (Thailand) in 2016, MNL48 in Manila (the Philippines) in 2016. More than ten sister groups have been created by Akimoto Yasushi so far, which will be expanded more and more. These are called “sister projects," and are similar to AKB48 but in different locations (Kiuchi, 2017, p.34).

Digital ethnography and the AKB48 fandom

Today, as digitalization progresses all over the world, the traits of communication within fandoms has changed. A modern fandom is predominantly a networked and online subject, which is also the case with the AKB48 fans.

The AKB 48 groups have spread translocally since the original AKB48 was organized in Tokyo in 2005. According to Piia Varis, the contexts for online activity are layered and polycentric (Varis, 2014, p.7). Digital ethnography is used in order to grasp the characteristic fan practices of AKB48, since members of the fandom communicate with each other and purchase commodities for the idols through online tools. In addition, the AKB48 fandom is understood as an example of polycentric and neoliberal phenomena.

Figure.1 The most popular single “Koi suru fortune cookie” (2013).

I will analyze the AKB48 fans on digital platforms and focus on their behavior, communication, and activities. Therefore, the research field will mostly be online. However, I also conducted face-to-face interviews. The common denominator among digital ethnographies is that they all include some kind of online data, and they all employ ethnography in the research process (Varis, 2014, p.2). Thus, the significance of an ethnographic study is not only the results of the research, but also the research process itself.

For instance, I conducted a face-to-face interview with Atsushi Ishikawa, who is part of the AKB48 fandom in Japan. From this interview, traits of the fan’s behavior and activities are revealed. Needless to say, it might be hard to generalize a fandom theory for AKB48 from one interviewee, but this interview can give us a certain point of view for this research. I also needed information and general theories of fandoms in order to collect data about the AKB48 fandom and describe and analyze its traits.

The AKB48 fandom and the translocalism

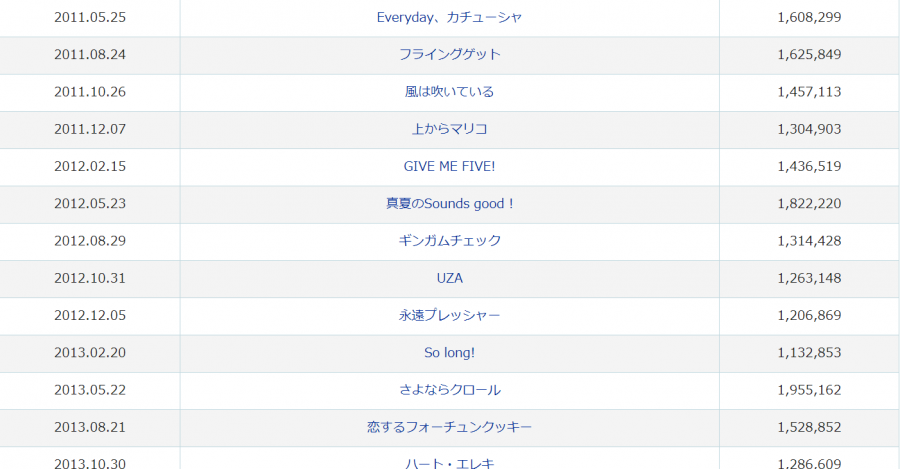

There is a history of the translocal (or transnational) spread of AKB48 culture. Since the authentic AKB48 was organized in Tokyo in 2005, the fandom has spread across Japan as a whole. “Since 2011, all of AKB48’s singles have sold over a million physical copies, including Sayonara Kuroru (2013), which sold over 1.9 million copies” (Kiuchi, 2017, p.32).

Figure.2 All of singles are sold over a million between 2012 and 2017.

AKB48’s 2013 single named “Koi suru fortune cookie (恋するフォーチュンクッキー)” has sold over 1.5 million copies, as shown in Figure 2 (bottom entry). The single brought a big boom in Japanese pop-culture in 2013, which was immediately spread outside of Japan as well. People in the fandom and non-fandom copied the dance of “Koi suru fortune cookie” and shared it on YouTube. Below, a YouTube video shows an example from a Kanagawa prefectural office (the 2nd largest city in Japan) composed of the governor, officials, residents, and tourists copying the “Koi suru fortune cookie”.

Many other people copied “Koi suru fortune cookie”, including staff working in Samantha Tabatha (a Japanese bag brand), staff working in CyberAgent (a Japanese IT company), as well as people living in New York, Detroit, and other international cities. These were all shared on YouTube. Each video was spread and viewed more than a million times all over the world. This trend evoked the strong fandom of AKB48.

As mentioned earlier, AKB48 has many sister groups in Japan and other Asian countries. That means that fandoms have spread translocally within Japan and spread transnationally/translocally among other Asian countries and cities.

If you look at the domestic sister groups, each of the xx48 idol cultures is spread translocally within Japan. Basically, the fans of a sister group form its local fandom. For domestic examples, the NMB48 fandom is mainly composed of the fans living in Namba or nearby. The HKT48 fans create their fandom locally, in Fukuoka prefecture.

On the other hand, AKB48 (the original group created in 2005 in Tokyo) did not only form a fandom in Tokyo, but also has a fandom that spread throughout the whole of Japan and into Indonesia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and beyond. This results from the fact that the original AKB48 group has appeared quite often on Japanese TV shows.

Figure.3 Each of sister groups has its own image color.

The first sister group named SKE48, from Nagoya, was created in 2008. The fandom is composed primarily of local fans, because members of the groups are largely recruited within the local area through auditions. This is also the case among the translocal fandoms in other Asian cities. Thus, each fandom of the sister groups has different polycentric behavior and activities, which largely depends on traits of each of the idol groups and cultural differences where the fans live.

We can look at the idol culture in Jakarta as an example. Since 90% of people in Indonesia are Muslim, the JKT48 fandom respects their Islamic culture. During Ramadan, the local idol group does not hold concerts out of religious consideration. Also, the costumes of the members of JKT48 are less sexualized compared to those of the original group. Below, the members of JKT48 dance to their single "Everyday Kachuusha", without wearing swim suits.

Another example, BNK48, from Bangkok, Thailand, shows a unique trait of the idol culture. This group was created in 2016, and is thus a relatively new group.

“Originally, in pop-culture of Thailand, so-called ‘good-looking people’ (like deep-set eyes) are commonly celebrated, which has been strongly influenced by Western culture” (Kishimoto, 2018).

Thailand idol culture, especially among female idols, has traditionally celebrated sophisticated and sexually mature figures. Thus, the Thai idols perform a more sophisticated singing and dancing style, which is quite common and similar to mainstream K-pop (Kishimoto, 2018).

Contrary to this, BNK48 brought new concepts to Thai pop-culture, since Japanese idol culture is inspired by a culture of cuteness, where female innocence and naivety is celebrated. The members of the idol group are not mature, experienced, and sophisticated, but rather they are naive, immature, and closer to the fans. In Thailand, BNK48 fans have cultivated a fresh pop culture around these immature idols. This is also the case with the other fans in the fandom. Furthermore, the Thai fandom is mainly composed of the fans of ages between 18 and 34, contrary to Japanese AKB48 fans, who are mostly between 30 and 50. In addition, 40% of fans in Thailand are female (Kishimoto, 2018).

As described above, the Jakarta, Bangkok, and also local Japanese groups are manufactured to include both the semiotic features that index the original AKB48, as well as local features.

Neoliberal consumption among the AKB48 fandom

There is a unique consumption behavior among the AKB48 fandom, which is based on commercial intent by the recording company. According to Maly and Varis, the neoliberal phase of globalization is “an era characterized by niched mass production, a logic of consumption and commodification in self-making, and a globalized market catering not only for the elites, but also for the ‘common people’” (Maly and Varis, 2015, p. 2).

The AKB48 fandom can be seen as an example of such neoliberal commodification processes. As Ishikawa says in the interview, there is an authentic fan’s motivation to purchase the singles to listen to the music, but also motivation to shake hands with or vote for their favorite idols.

The fans do not only purchase the singles themselves, but also in order to obtain tickets for “handshaking events” and ballot papers for “general elections”. Those commodities are part of the singles. “What concerned those in the industry is that AKB48's sales were pushed by a large handshaking event involving over 220,000 fans” (Kiuchi, 2017).

Figure.4 You can shake hands with your favorite when you buy the CD.

The general elections are conducted by the fans. Voters fill out ballot papers to determine the most popular member in AKB48 and the sister groups. One of the members is elected as the most popular and is given the opportunity to appear in the center of the group on both the CD cover images and on stage during live performances.

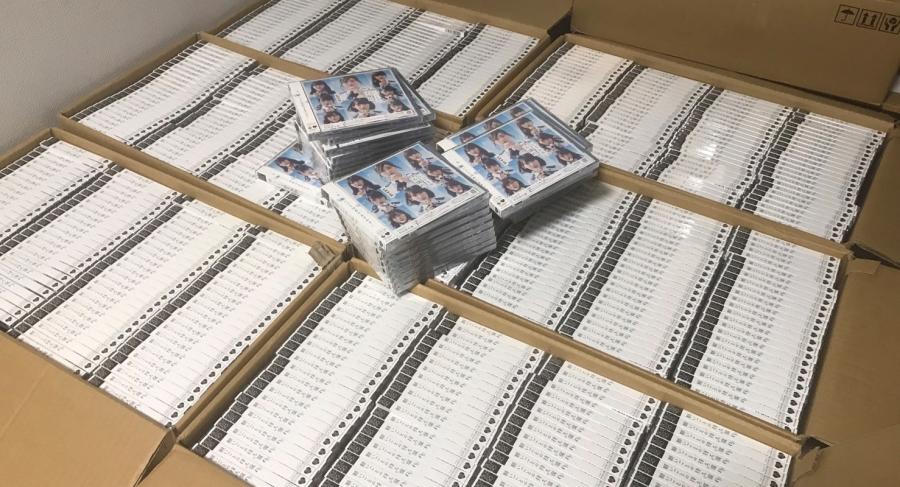

The ballot paper is usually an accessory of the single that the fans can buy right before election seasons. A fan who wants to see and meet their favorite member at a TV shows or concert buys CDs to vote for her. A fan can buy as many CDs as they want to vote for a favorite member. “Although the general elections have been widely criticized, its social impact is nonetheless immense. The election in 2012 attracted almost 1.4 million votes” (Kiuchi, 2017, p.35). The image below (Figure.5) shows singles that were collected by a fan of AKB48 who bought about 8,000 euros worth of ballot papers to vote for his favorite.

Figure.5 If you want to vote to your favorite, buy the CDs as many as you can.

“[Logically,] this strategy makes sense because the group consists of over 100 singers, and it is practically impossible for all members to appear on TV or other media upon the release of a new song. Therefore, Akimoto allows fans to voice who they want to see the most and participate in the simulation‐game‐like experience. Not only does the election affect who will sing a new song but also who will stand in and near the middle of the stage” (Kiuchi, 2017, p.35).

An irregular feature of this fandom is a convention that states that the members of AKB48 and other sister groups are not allowed to date or be in love with someone. This principle was not advocated by Akimoto Yasushi (the chief producer), but is seen as a convention among the members of AKB48 and the other sister groups. This practice keeps their image "pure" and authentic for the fans. In other words, the idol’s purity and authenticity are seen as commodities among AKB48 fans. Consequently, an idol’s “scandal” is often exposed in magazines and other outlets. If a member does not obey the convention, she is seen as betraying the fans.

AKB48 is encouraged to keep a close relationship with their fans. A concept behind AKB48 is “idols you can meet.” The fans can seetheir idols perform every day and feel very close to them in the local theater. There is an AKB48 Theater in Akihabara (Tokyo) that holds a concert every day. The fans join the concerts to see the idols perform on stage, but also to have simulation-game-like experiences through seeing the processes of growth of the idols (Kiuchi, 2017, p.35).

For the fans, the process of growth of the idols is commodified. Additionally, the business model has gradually become commonplace among other idol groups. “Music groups other than AKB48 have similarly utilized business strategies such as merchandising such as apparel and stationary, and handshake events” (Kiuchi, 2017, p.35). Hence, what has been commodified here is not only the idol’s body but also their performed personalities. Such harnessing of personalities and communicative competence for economic gains as seen among idol culture is also an important part of neoliberalism.

The AKB48 fans as compassionate observer

If we understand fan-idol interaction as the consumption of likable personalities and intimacy, AKB48 fans are not deviant. In that sense, they are similar to Western fans who also identify with celebrities' biographic narratives. We can see for example how Lady Gaga's fans interpret the monstrosity of her celebrity image as an embrace of difference, and note how Lady Gaga communicates intimately with fans on Twitter (although she does not regularly shake hands). Dylan (19, straight, American) showed his appreciation of her social media use:

“[Without Twitter] I would never get to know anything about her unless she was on TV…And thank goodness for [social media], or else we wouldn’t know half the stuff we know about her!” (Click, Lee and Holly, 2013, p. 375)

Lady Gaga shares a range of personal and insider information with the "Little Monsters" (her fans) through social media. Thus, many Monsters are able to develop feelings of intimacy with Lady Gaga. This suggests that social media both facilitates and enriches communication between Lady Gaga and the Little Monsters (Click, 2013, p. 375). In that sense, the fame of AKB48 groups and Lady Gaga are mainly and devotedly built on fan-idol interaction.

“The act of creating an imaginative personal narrative about a favorite idol provides a medium that permits a fan to have a kind of pseudo-intimacy with that idol” (Galbraith and Karlin, 2012).

As stated above, the concept of being “idols you can meet” is embodied in the AKB48 Theater in Akihabara, where fans can see their idols perform every day and feel close to them. Because of this system, the fans can watch their idols' growth from close up. In this sense, the shaky performance with a dedication to become better (self-effort) is also likeable among fans. Ishikawa, a part of SKE48 fandom, explains about the idols he follows:

“My favorite is Jurina Matsui, belonged to SKE48 for almost 5 years. I have watched over the idol since I saw her in a TV show when she was still age 15. She really looked radiant at that time. Of course, in general, it is better that idols are good at singing and dancing. It is not desirable that they are not good at their performances. If not so, an idol who intentionally pretends to be immature and naive will appear. More, you cannot say their shortcomings and immaturities will necessarily link with their popularities or attractions among fans, but I like to watch over her growth. Then, each member of SKE48 has its own personality, character and originality.” (Ishikawa, 2018)

Even if a member of AKB48 does not perform sophisticated singing and dancing at the concerts, the fans will not mind it, because the immaturity itself is a commodity among the fans.

Idol culture, similar to celebrity culture, emphasizes industrial production of highly visible figures in the media. The interview brought us an important suggestion that idols’ purity, immaturity, etc. are linked with the audiences’ consumption and production practices. Idol culture harnesses and commodifies the affective energy of fandom. Governing by using the energy of those being governed is also an important feature of neoliberalism. However, idol culture is different from Western celebrity culture, as the popularity of idol is based on intimate and close idol-fan interaction.

AKB48 Fandom

We saw how the AKB48 fandom has spread translocally within Japan and transnationally among overseas cities. The different traits of the fandoms are mainly influenced by cultural circumstances where the fans live. Indeed, the traits of fans have strongly connected neoliberal consumptions. Moreover, fan-idol interactive intimacy can be also seen in Western fandoms, such as that of Lady Gaga.

In the AKB fandom, the members are not necessarily a mature entity, contrary to fandoms of Western culture. Rather, the process of growth and shortcomings of the idols arouses a feeling of pure and authentic attractiveness among the fans, which is heavily commodified.

References

Click, M. A., Lee, H., & Holly, H. W. (2013). Making Monsters: Lady Gaga, Fan Identification, and Social Media. Popular Music and Society, 36(3), 360-379.

Galbraith, P. W., & Karlin, G. J. (2012). Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture. New York: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN.

Ishikawa, A. Face-to-face interview. 2018.

Kishimoto, M. (2018, July 11). 「BNK48」タイで旋風, 未完成な姿 恋するファン. Retrieved from Nikkei Inc.

Kiuchi, Y. (2017, February 15). Idols You Can Meet: AKB48 and a New Trend in Japan's Music Industry. Wiley Online Library, 50(1), 30-49.

Maly, I., & Varis, P. (2015). The 21st-century hipster: On micro-populations in times of superdiversity. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 14.

Records, G. W. (2013, March 29). Largest pop group. Retrieved from Guinness World Records: http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/largest-pop-group/

Varis, P. (2014). Digital ethnography. Tilburg Paper in Cultural Studies, 2,7.