Viktor Orbán: An Authoritarian Right Under Europe’s Nose

All publicity is good publicity: those must be words to live by for Hungary’s current ruling Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán. Recently, he made headlines all over international news for introducing his human rights-violating anti-LGBTQ+ law. However, that is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the Hungarian’s ideologies and actions. Public spats with the EU, taking control of his country’s media landscape, and proclaiming that his regime is an 'illiberal democracy' are just a few of his "achievements". This article will analyze how Viktor Orbán uses both the traditional Hungarian news landscape and social media landscape to reveal how he is slowly but surely working towards an authoritarian regime, and how nobody is stopping him.

Orbán and Hungary’s History

Before Orbán was involved in politics, Hungary had been under the rule of the Soviet communist regime, from 1949 up til 1989. The year prior to its demise, Orbán became one of the founders of the Party of Young Democrats, known as Fidesz. His first claim to fame came in 1989, at the ceremonial reburial of former premier Imre Nagy, who led the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. In a speech, he called for free democratic elections, as well as for the Soviet troops to withdraw from Hungary, which subsequently came to pass in 1990 and 1991 respectively. This resulted in him gaining popularity, as the Hungarian people saw him as the furthest thing away from a communist at that time.

Orbán would taste his first true political victory in 1998 when he became prime minister for his first four-year spell. He took no time implementing his vision, appointing young, first-time ministers, working towards a free market economy for his country, and promising active involvement with the rest of Europe.

After some lesser years following the end of his term as prime minister, the financial collapse of Hungary in 2008 paved the way for his party to win with an overwhelming majority in the 2010 elections. Once again, he found himself in the position of the most powerful man in the country, and this time, he was not going to give it up. He is still in office as of 2021, with him showing no signs of wanting to step down.

Orbán’s Ideology

The Hungarian ideology is made up of several different parts, each of which shall briefly be discussed in this section of the article.

To begin with his nationalist conservative stance. He has given Hungarian-born Hungarians outside of the country the right to vote, a move that simultaneously raised his popularity and cemented his position of power. Meanwhile, he has put up a barbed wire fence as well as taken other measures on the border with Croatia in an attempt to keep out asylum-seekers (Stojanovic & Gera, 2015). Moreover, he declared an emergency in two southern counties bordering Serbia for similar reasons (BBC News, 2015). This gives clear indications that he does not want his country to be filled with outsiders, like foreigners and non-Christians, attempting to create a united Hungarian people. Thus, xenophobia is also part of Orbán's ideology.

His conservatism shines through in his religious, anti-LGBTQ+ stance. This stance garnered worldwide attention when in June of 2021 a bill was passed that prohibited the “portrayal and promotion of gender identity different from sex assigned at birth, the change of sex and homosexuality” in schools (Szopkó, 2021). Originally an anti-pedophilia bill, this last-minute change is a clear indication of the homophobia in Orbán's ideology. It is also in clear violation of the EU’s fundamental values, causing another strain on the country’s relationship with the EU.

In July 2014, Orbán gave a speech in which he declared that his regime aimed for an 'illiberal democracy'. In such a state, there are elections held, yet there is close to no transparency regarding what those in power actually do. Civilians do not have civil liberties, and thus there is no open society (O’Neil, 2012). A year earlier he already performed an act that is characteristic of illiberal leaders. He changed the constitution that was written in 1989, to restrict political campaigns to state media and restrict the power of the constitutional court, as well as requiring students that were given a state grant to stay and work in Hungary for a number of years or pay back their grant (BBC News, 2013).

This concept of an 'illiberal democracy' is problematic in its very nature. Democracy revolves around the Enlightenment ideals of liberalism, rationalism, and equality. In a democracy, the people are free to express themselves and have the power to influence politics. Therefore, by making it illiberal, as well as restricting the people’s freedom through his control over e.g. the media landscape, he takes away equality too, putting himself and his government above the rest of the people. If you knock over those 3 pillars of democracy, there is no democracy left (Sternhell, 2008.).

As a consequence, Hungary is still officially a democracy, but a crumbling one at best. Orbán is slowly but surely forming his state towards being an autocracy. This is “a system of government in which supreme political power to direct all the activities of the state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject to neither external legal restraints nor regularized mechanisms of popular control” (Johnson, 2005). Aside from taking control of the country’s media landscape, which will be covered more extensively later on in this article, Orbán has also made other moves in order to preserve and cement his position of power. He has periodically instated right-wing judges in the country and funded supporters of his into the nation’s business elite. These supporters then return the favor, providing funds for his political endeavors (Rhodes, 2020). On top of this, he is still yet to lift the state of emergency he instituted in March 2020, giving him the power to make decisions without having to pass them through parliament first.

Orbán in the Media

In order for Orbán's positive “people’s president” image to be preserved, the prime minister has gone to quite extreme lengths. In 2018, the Central European Press and Media Foundation, known as KESMA, was established. This media council holds over 500 media publications, unrivaled by anything like it across Europe. According to Zoldán Kovács, Secretary of State for International Communication and Relations, together with Fidesz media holdings they have managed “nearly 50 percent of the Hungarian press to convey the government’s position.” (Tamás, 2021). So, in the Hungarian media landscape, he is portrayed exactly as he wants to be.

He also has an efficient social media team. He is verified on both Facebook and Instagram, on which identical posts are posted. The contents of these are reasonably varied too.

Some of the posts promote clear anti-immigration, anti-Brussels, and pro-Hungarian people discourses. Figure 1 reads "Don't let Brussels decide for our children!", indicating Orban's desire to leave the EU in the foreseeable future.

Figure 1: Orban on Brussels

Other posts are used to denigrate and invalidate his political opposition. Figure 2 shows Orbán and his fellow party members laughing at one of the more influential figures of Hungary's opposition, Péter Jakab. The caption calls him a clown, indicating his political ideas are laughable to Orbán. This is meant to further de-popularise Jakab.

Figure 2: Orban on his opposition

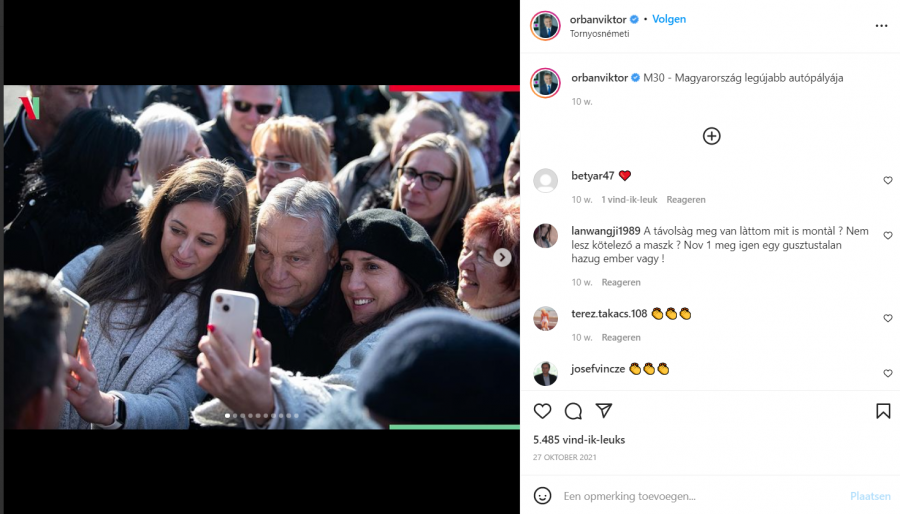

Then the third category consists of more regular social messages, such as pictures of him meeting up and having a good time with his supporters, family, and friends. These sorts of posts are meant to boost his image as a popular and loved man by the people. Figure 3 shows Orbán taking the time to take pictures with some of his supporters.

Figure 3: Orban with his followers

It is in the international media that he is portrayed a lot differently. Here the main focus is on him being presented as anti-EU and anti-LGBTQ+. Dutch newspaper Trouw made a big headline about this surrounding the anti-LGBTQ+ law in June. Whereas in Hungarian media and his own social media, he is presented as a strong, confident leader, in international media he is seen as a lot more dramatic and less formidable. German news outlet EUobserver compares his antics to those normally seen in a soap opera, and the French Politico even matches it with the words “family drama”.

See, contrary to his controlled Hungarian media landscape, in international media, he, as the actor, is not in control of the information flows to suit his goals. His international character, outside of his control is rightfully sketched to be blatantly anti-EU and anti-LGBTQ+.

Orbán, Algorithmic Activism, and Big Organizing

In addition to his effective social media presence, Orbán also makes use of big organizing. “Big organizing is what leaders do in movements that mobilize millions of people” (Bond & Exley, 2016). Orbán's party, Fidesz, created a large group of online followers to spread positive messages about the Hungarian government online. These volunteers were given posts, texts, and other forms of content by members of the party, which they then had to spread across Facebook groups and other places on social media. This way, the average Hungarian citizen would almost always be confronted with pro-government propaganda when going online (Zoltán, 2018). This is a form of algorithmic populism (Maly, 2019), and is all about creating a large online following supporting their political views and ideas, to back up the politician's claim to be a man of the people, representing what the people want.

This works in three steps. First, there is the populist discourse, produced by Orbán's social media accounts. Secondly, there is the uptake, which is generated through these volunteers, resulting in the algorithm picking it up. Thirdly, there are the media voices, echoing the sentiment that Orbán is indeed a man of the people. Since he controls most of the Hungarian media landscape and influences the social media landscape in this way, these voices are not at all hard to come by for him.

The previously mentioned ‘child protection act’ that was introduced in June 2021 did not only cause quite a stir in international legacy media but also among Hungarian people. Around 10,000 people took to the streets of the capital Budapest to protest against this new law. On social media, several human rights organizations posted about it too. In particular, the post by Amnesty International went viral on Instagram. It got shared so often that it was hard for anyone to go on to the app without coming across it. This kind of activism is known as algorithmic activism. This type of activism contributes to spreading the message of a politician or movement, by interacting with the post in order to trigger the algorithms of the medium, so that it boosts the popularity rankings of this message and its messenger (Maly, 2019).

Orbán: Both the Hero and the Villain

This article has provided a breakdown of Orbán's political ideology, a look into his presentation in different media landscapes, and an analysis of his use of big organizing and his role in regard to algorithmic populism and activism. It has become clear that he is slowly but surely working toward an authoritarian state, in which he holds the power. While he is successful in convincing many Hungarians that he is a hero, equally as many people outside of Hungary can not help but see him as a villain.

References

BBC News. (2013, March 11). Q&A: Hungary’s controversial constitutional changes. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

BBC News. (2015, September 15). Migrant crisis: Hungary declares emergency at Serbia border. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Bond, B., & Exley, Z. (2016). Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can Change Everything. Chelsea Green Publishing.

De la Baume, M. (2021, March 3). Orbán walkout shakes up European (political) family drama. POLITICO. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

Fidesz | Party History, Ideology, & Facts. (2018, October 30). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Hegedüs, D. (2021, March 5). [Opinion] Orbán leaves EPP group - the beginning of a long endgame. EUobserver. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

Hungary | Culture, History, & People. (2021). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 10th, 2022.

Johnson, P. M. (2005). Autocracy: A Glossary of Political Economy Terms - Dr. Paul M. Johnson. A Glossary of Political Economy Terms. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Maly, I. (2019, November 26). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

O’Neil, P. H. (2012). Essentials of Comparative Politics (Fourth ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Rhodes, B. (2020, June 18). American Orbánism. The Atlantic. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Sternhell, Z. (2008). How to Think about Fascism and its Ideology. Constellations, 15(3), 280–290.

Stojanovic, D., & Gera, V. (2015, September 17). Croatia puts army on alert as it reels from migrant influx. The Seattle Times. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Szopkó, Z. (2021, July 9). Hungary’s new anti-LGBT law is mostly about the upcoming elections. English. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Tamás F. (2021, March 23). Orbán’s influence on the media is without rival in Hungary. telex. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Tóth, C. (2014, October 23). Full text of Viktor Orbán’s speech at Băile Tuşnad (Tusnádfürdő) of 26 July 2014. The Budapest Beacon. Retrieved Januari 10th, 2022,

Van Hennekeler, R. (2021, September 5). Voor Viktor Orbán is de EU een ideale pispaal. En de Hongaren? Die waren nog nooit zo pro-EU. Trouw. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

Viktor Orban | Biography, Ideology, & Facts. (2021, June 6). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

Zoltán H. (2018, January 30). A Fidesz egyik Facebook-katonája elmesélte, milyen virtuális hadsereget hozott létre a párt. 444. Retrieved December 9, 2021.