Is Wie Is de Mol making us paranoid?

Saturday evening, March 5, 2022, is the night millions of Dutch television viewers have been waiting for: the finale of the 22nd season of the hugely successful TV show Wie Is de Mol (WIDM). Last year, the finale was watched by 3.3 million viewers. In this article, we discuss the role of collective intelligence, the ways in which the show provokes distrust in its fans, and the special ‘hybrid media’ element brought in by its final live event.

Who is the What Now?!

For Dutch readers, this show probably doesn’t need an introduction, but for the rest: WIDM is a unique reality TV game show in which ten (this year eleven) contestants try to accumulate as much prize money as possible in team-oriented tasks, while one contestant doubles as a secret saboteur. This ‘Mole’ works in secret to sabotage the efforts of the group, so that as little money as possible will be accumulated by the contestants. The show also functions as a travel show, and is set in beautiful locations all over the world. This season takes place in Albania. Based on a Belgian template, it has been a staple of Dutch TV landscape since 1999. The show invites extensive participation from its audience, with different kinds of (digital) media literacies and knowledge brought into play through collective intelligence and extensive communal exchanges. Besides competing with each other, audience members are in competition with the makers of the show. They try to crack the code set out by the program makers and ‘beat the show’ by finding out the identity of the Mole before the season ends.

These exchanges take place across a range of platforms that are part of the show’s ever-growing franchise, like the official website with interactive forum, the talk show Moltalk, the Wie Is de Mol? app, a weekly podcast on Radio 2 , the YouTube show Niet de Mol in which Splinter Chabot talks to the eliminated contestants, social media platforms (@IkBenDeMol [“@IAmTheMole”]), etc.). Besides, there are many fan-initiated media objects such as YouTube channels.

As a result of increasing digitalization during the show’s lifespan, thanks to which fans have more opportunities to come together, and more advanced media literacy, the hints and montage techniques have become exceedingly complex and diffuse over the years. In the viewing attitude it engenders, WIDM resembles narratively complex TV-series of the “conspiratorial” kind, like The X-Files or Lost (Brinker 2015). Training their viewers to decode complex narratives, such series in effect offer a “cognitive workout,” a honing of problem-solving and observational skills (Mittell 2015, 35). To take part in the community takes up a lot of time and cognitive effort, as such TV series demand a “meticulous, almost obsessive attention to detail and the readiness to engage in time-consuming and laborious close readings of scenes and even individual frames” (Brinker 2013, 4). In their collective ‘hunting and gathering’ activities, the Molloten, as the fan community is called,[1] carefully analyze clips frame by frame – for instance in the intro sequence. Television like this sets a high threshold for expected media literacy and information skills.

What makes us (dis)trust a candidate?

After an engaging session we had together with students for the course Participatory Art in the BA Online Culture in 2020, we wrote an article about the media networks and audience engagement surrounding this show (forthcoming in Quarterly Review of Film and Video). Next, we decided to zoom in on a specific element in audience responses: the role of (dis)trust. The show’s complexity and audience manipulation lead to a ‘paranoid’ viewing attitude, or at least asks of viewers to alternately adopt trusting and distrusting viewer’s position with regards to both its candidates and the show runners. After all, not only can the Mole not be trusted: nothing is what it seems, and everything can be a clue. This includes the possibility of being misled through camera work, editing, hidden ‘hints’, red herrings, and so on.

How do fans calibrate trust and distrust in their interpretations of the episodes? What is the role of hermeneutic activities (e.g., analysis of text and image, regulating [dis]beliefs, information literacy) in their attempts to unmask the mole? To examine what kinds of mechanisms come into play when audience members determine whom to trust and distrust, we led a weekly focus group with ten fans, whom we ‘followed’ in their discussions of each episode of the present season. As researchers, we ourselves were involved as active participants in these discussions. We haven’t finished collecting our data, but we can give you a teaser here.

While watching the show, the audience is continually asked to evaluate the validity of the information they are presented with. They pay close attention to the ways in which the contestants act during the assignment. Who is working hard to earn as much money as possible (and is therefore trustworthy) and who seems to be working against the group’s efforts (and is therefore suspicious)? A more objective method is “follow-the-money”, calculating which contestants bring in the most and least amount of cash. The confessional moments lead to speculation as well, as there is a distinct pleasure to trying to deduce who is lying to the camera, and who is sincere. Last, there are (often impossibly complicated) secret clues which the makers have hidden in the final edit of the show.

Is Everon lying here?

It was interesting to notice how certain types of knowledge and skills were distributed over our small group. To use our collective intelligence, roles were almost immediately assigned: we have someone with knowledge of psychology, someone who knows everything about the show and had correctly identified the Mole for earlier seasons, someone who knew how tarot cards are supposed to work. Besides, everyone had some piece of knowledge about the contestants and other TV-shows they have been in. Participants were clearly more ready to consider certain ‘evidence’ and interpretations offered by someone based on their authority and expertise in any of these areas, than when this expertise was lacking.

‘These meetings… they create tunnel vision!’

Then, there are those who are simply very persuasive and contagious in professing their beliefs. Two of our participants had been confident that Everon is the Mole from the beginning, and soon convinced several others to join them in the ‘Everon tunnel’. ‘Being in a tunnel’ is the show’s lingo for confirmation bias: once you’re convinced someone is the Mole, you start to see signs everywhere, and interpret every situation as confirming that knowledge. Of course, in this particular case, it helps that Everon made it all the way to the finale.

For some, reliability of a candidate is ‘just’ based on feeling or intuition. For others, it is connected to likeability: they reported a tendency to trust candidates they find sympathetic and conversely, being more suspicious towards those they like less. In our group, Arno was not popular: because some participants disliked the way he (self-)presented, he was trusted less. This can be reinforced by other media performances: it appeared to make a slight difference whether you know Kim Lian from the evil character she portrayed in Onderweg naar Morgen, or as a friendly presenter of the Kids Top 20. Another factor was a candidate's profession (‘he’s an actor, he would be able to fake this’; ‘she’s in sports, she just wants to win’; ‘no way this guy’s shy, he’s a BNN presenter!’; ‘he’s a stylist, he just has an eye for detail’).

Trustworthiness was linked to all kinds of characteristics that participants ascribe to the candidates. Right away, and guided by the show’s representations, participants were subdivided into types like the macho, the smart guy, the goody-two-shoes, or the fanatic, and this was then used to argue for or against the person as the ‘Mole’. Fans also project themselves into the shoes of either the Mole or a candidate, imagining what their strategy would be.

'Join us in the Everon-tunnel....'

We found instances of double, triple, or even quadruple bluff in the ways in which the contestants are presented. In our collective interpretations, our group gave many instances of reverse psychology (‘Kim Lian is acting too much like a Mole, she can’t be it’) and reverse-reverse psychology: ‘Kim Lian is ‘molling’ in a ‘too obvious’ way, but maybe...... she expects people to think this, and that’s her strategy as the Mole!’ The adage ‘nothing is what it seems’ means that you can endlessly look for double and triple layers of deception. There is a certain pleasure in this, but also frustration: for some participants, this undecidability leads to defeatism, ‘it is impossible to know’.

Our participants demonstrated an astute awareness of being manipulated by the show itself (‘they had 60 seconds to deliberate, yet we only see 10. We don’t know what has been said in the meantime!’). We discussed to what extent their beliefs have been influenced by those of other fans like friends and family, or those posted on online forums, social media, and statistics from the Mol-app. This way, we hope to assess how fans of the show come to assessments of reliability and trustworthiness, and what role media literacy plays in this process.

‘Liveness’: hybrid media

Besides giving us an outlet for paranoid feelings, part of the ongoing appeal of this show lies in the fact that it does not just take place online. WIDM, obviously, ‘happens’ in living rooms all over the country. It is of vital importance not to lag behind in watching the latest episode: in the Dutch context, it is very hard to avoid spoilers, online and offline (similar to what Game of Thrones achieved world-wide). But there are additional ‘real-life’ events as well. Since 2001, de ‘Molloten' meet up in offline settings to evaluate the previous season. This molfanatenbijeenkomst (‘Mole fanatics meeting’) started with about 50 fans and a couple of contestants in a small theater in Utrecht, but has been scaled up to the Molfandag (‘Mole fan day’) and to the present-day Wie is de mol? Experience, a professionally organized event that includes meet-and-greets, a special auction with objects from the show, and pop quiz.

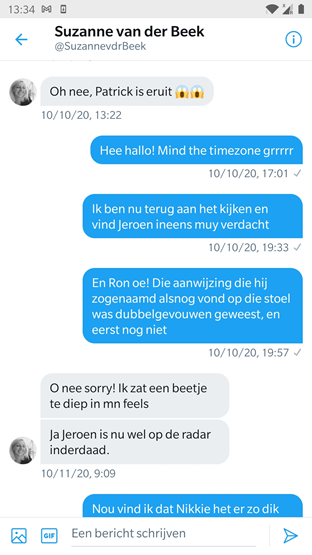

Suzanne ruining things for Inge in 2020

Since 2015, the show organizes a live event around the big reveal of the Mole at the end of the season, open for fans to attend. Participation has become so coveted that the show has had to organize watch parties in theaters around the country to redirect fans from this central meeting. In an on-demand and streaming culture, WIDM injects the ‘aura’, an event-like sense of co-presence, back into the media experience. Walter Benjamin (1999, 3) famously describes this in terms of a waning of the aura, the “presence [of the work] in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” With digitalization, physical co-location becomes less central. Through interaction via different online platforms, audiences have found new ways to participate in works with others in different locations. Yet, the particular participation around shows like WIDM brings back and builds onto the notions of co-presence at a certain time (and, in the case of the live shows, co-location at a certain place). It does so, not outside of, but through networks of convergent media. WIDM makes excellent use of the hybrid media system, by tapping into the affective dynamics of 'liveness’ (Kim 2020) in the context of the digital media environment.

We don’t know about you, but we cannot wait for Saturday, when we will finally find out how we have been manipulated and be amazed by all the clever shenanigans that this year’s Mole has been up to. Whether you will be present live outside of the studio in Amsterdam, watching in a movie theater somewhere in the country, or from the comfort of your own home, alone or with friends: have fun unmasking the Mole!

[1] The term “molloot” is a play on words that combines “malloot” (roughly: “fool” or “poser”) with “mol” (“mole”). It refers to the dedication of the show’s fan base. It also conveys that one must be crazy to be so devoted to unmasking the Mole, and that there is the distinct possibility of being fooled, misguided by confirmation bias or ‘tunnel vision’.

References

Benjamin, W. 1999. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by H. Arendt, H. Zorn, and Trans. 1936, 211–244. New York, NY: Pimli.

Brinker, Felix. 2015. “Hidden Agendas, Endless Investigations, and the Dynamics of Complexity: The Conspiratorial Mode of Storytelling in Contemporary American Television Series.” Poetics of Politics: Textuality and Social Relevance in Contemporary American Literature and Culture, ed. Sebastian M. Herrmann, Carolin Alice Hofmann, Katja Kanzler, Stefan Schubert, Frank Usbeck. Universitätsverlag Winter.

Brinker, Felix. 2013. “Narratively Complex Television Series and the Logics of Conspiracy – On the Politics of Long-Form Serial Storytelling and the Interpretive Labors of Active Audiences.” “It’s Not Television” conference, Goethe Universität Frankfurt/Main, Germany.

Kim, Suk-Young. 2020. K-Pop Live: Fans, Idols, and Multimedia Performance. Stanford University Press.

Mittell, Jason. 2015. Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York UP.