From Front National to Rassemblement National

Rassemblement National should become the new rallying cry for nationalists in France and make Front National salonfähig. How Marine Le Pen and Steve Bannon attempt to pour old nationalist wine in new bottles.

Rassemblement National! This was the main message that Marine Le Pen wanted to convey at her party congress in Lille last Sunday. In response to her crushing defeat against Emmanuel Macron last year and in the hope of ridding herself and her party of persisting neo-nazi connotations, Le Pen proposed to change her party’s name into Rassemblement National, meaning ‘national gathering’. In addition, she convinced her members to strip her father Jean-Marie Le Pen of his honorary membership, finally cutting all the remaining ties with the anti-Semitic founder after his expulsion from the party in 2015.

Rassemblement National (Populaire)

According to Marine Le Pen, although “the name Front National bears an epic and glorious history that no one must deny”, a name change had become imperative as it had proven to be a “psychological barrier” for French Voters during the last elections: "without a name change, we will not be able to forge alliances. And without alliances we will never be able to take power". “It must become clear to all that we have become a party intent on governing”, Le Pen added.

Being racist, xenophobic and nativist is simply how others see our party's program, and the others are wrong.

Ever since her election in 2011, Le Pen has been set on making FN a more acceptable party while staying true to the party’s extreme right roots. Her suggestion to change the party name must also be seen in that light as Rassemblement National is remarkably similar to Rassemblement National Populaire, a fascist party that supported the Nazi’s during the Second World War. Moreover, the now ostracized Jean-Marie Le Pen already adopted exactly that name prior to the elections in 1986.

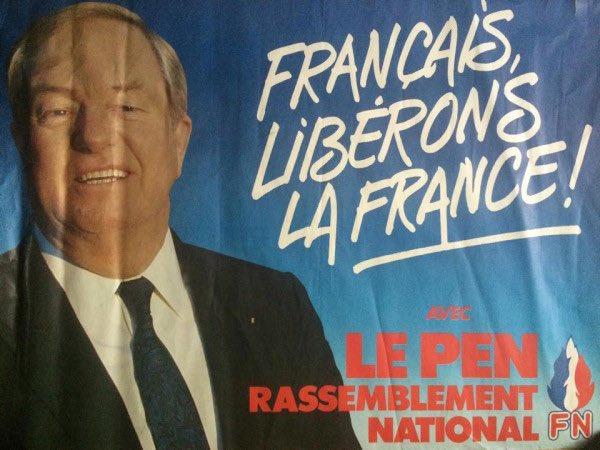

The 1986 poster for Jean-Marie Le Pen's Rassemblement National

As such, the sincerity of Le Pen’s motive for sanitizing the party’s image is pulled into question by the choice for this particular name. Recognizing the electoral importance of her father’s disciples for the party, it seems as if the decision for Rassemblement National is as a way of keeping the supporters of Le Pen senior on board, while vying for the support of voters whose history is a little spotty.

This becomes even more plausible if we go by the words of Guillaume Tabard in Le Figaro. He argues that the cause for FN’s decline in popularity was not to be found in the party name or its fascist roots. Instead, the cause lies with Marine Le Pen herself, who seems to have lost most her credibility after the 2016 presidential debate with Macron, in which she left a dubious impression.

Bannon: “Let them call you racists. Let them call you xenophobes. Let them call you nativists. Wear it is a badge of pride.”

In fact, a substantial part of FN’s members are longing for a return of Le Pen’s niece Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, who is more conservative, more nationalist and therefore more appealing than her aunt. Although Marion formally left politics in early 2017, just last month she made an appearance at the Conservative Political Action Conference, a conference where UKIP’s Nigel Farage and former Breitbart’s Steve Bannon were welcome guests. In a gloomy speech, Marion echoed Trump's nationalist rhetoric, arguing for the historical continuity of her nation.

Steve Bannon to the rescue

In the light of Marine Le Pen’s image problems and her niece’s flirt with the American extreme right, it should come as no surprise that the FN-leader had invited a special guest to spice up the party congress; none other than Steve Bannon himself. The narrative of his address was as to be expected: the political establishment and fake media are trying to keep the populist movement out of power with their demonizing rhetoric. Ultimately, however, the worldwide populist movement will prevail, Bannon argued: “history is on our side”.

At first glance there seems to be nothing new here. But nearing the end of his speech, Bannon had something special in store for the attendants: “Let them call you racists. Let them call you xenophobes. Let them call you nativists. Wear it is a badge of pride.”

Even though this might seem like nothing more than a catchy tricolon to end his speech with a rhetorical bang, Bannon did something quite remarkable here: by encouraging his audience to identify with these terms as badges of honor and pride, he tried to empty these pejoratives of their negative connotation. By doing so, Bannon effectively normalizes these terms by lifting them out of their pejorative context and remodeling them into positive signifiers of group membership. Being racist, xenophobic and nativist is simply how others see our party's program, and the others are wrong. This move detaches FN-members from the societal values attached to healthy public discourse by removing any form of shared assumption from debates. When confronted with such pejoratives, they can simply shrug it off: "Vous pensez que je suis raciste? Merci beaucoup!". It deepens the divide in society, making it impossible to find common ground in an already polarized public sphere.

This goes to show that both Bannon and FN have gone completely off the deep end, and that Le Pen’s intent of 'de-demonizing' the party’s image has turned out to be nothing more than empty rhetorical shell. If any, her changing the party name and Bannon's encouraging the FN-members to wear pejorative epithets as badges of pride only serve to justify the message that Front National has been preaching ever since its establishment: racism, xenophobia and nativism are just what France now needs.

Rassemblement National is old wine in new bottles and Jean-Marie, in spite of pretending otherwise, is laughing up his sleeve.