“Broooo do I have ADHD?” Self-diagnosis and the commodification of mental health disorders on TikTok

Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, many teenagers experienced increased levels of depression and anxiety (Shepherd, 2021) and turned to TikTok as a place to vent and find a sense of community and belonging (Mellor, 2021), often leading to self-diagnosis. The effectiveness and safety of this platform as a safe space to open up about mental health issues is questionable, but what exactly are the risks of performing these private discourses on public platforms such as TikTok?

Mental health content on TikTok

Mental health has become a very popular topic on TikTok, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. TikTok responded to the explosive popularity of (mental) health content by launching their ‘Wellness Hub’ (figure 1) in April 2021 where users can find a confluence of health-related content, including topics such as nutrition, fitness, life advice, and mindfulness.

Figure 1. Tiktok’s Wellness Hub

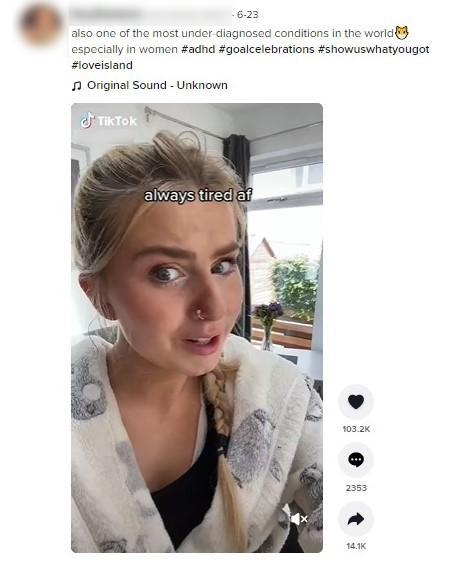

As this type of content became more and more popular, numerous content creators have taken advantage of the trend in order to grow their following on TikTok. In aiming to relate to the broadest audience possible, a significant part of mental health-related content seems to pathologize common symptoms that many individuals experience at some point in their lives. While these symptoms could certainly indicate neurodiversity, this is not necessarily always the case (James, 2021). Examples that are discussed on the platform are feeling exceptionally tired (figure 2) or being clumsy (figure 3) as symptoms of ADHD in women.

Figure 2. “Symptoms of ADHD that nobody talks about”

Figure 3. “Symptoms of ADHD in women”

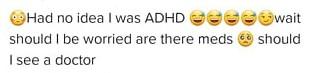

These videos evoke a strong sense of relatability which causes some TikTok users to question what this says about their own mental health and whether they should take these videos seriously in judging if they actually have a mental health disorder. This sense of relatability could, in turn, potentially lead to increased anxiety and the over-diagnosis of mental health disorders (van Niekerk, n.d., as cited in Greig, 2021). Figures 4 and 5 show two comments on the video shown in figure 3, from users who appear to relate so much to the mentioned symptoms that they begin to question whether they actually have ADHD.

Figure 4. “Broooo do I have ADHD?”

Figure 5. “Had no idea I was ADHD. wait should I be worried are there meds. should I see a doctor”

The commodification of mental health

The popular interest in mental health content seems to be used in order to have as many users as possible spend as much time as possible on the platform. This is not particularly surprising, as TikTok is a capitalist medium that generates profit by selling audiences, users, and/or content, and is based on private ownership; on TikTok, voice depends heavily on money (Fuchs, 2014). TikTok is thus not free from particularistic controls. The independence from economic and political power, however, is exactly what philosopher and sociologist Jürgen Habermas (1991) stressed to be so important for a strong public sphere in which society can engage in critical public debate. In Fuchs’ (2014) words, the particularistic control of social media “limits, feudalizes and colonizes the public sphere” (Fuchs, 2014, p.78).

On TikTok, voice depends heavily on money

At first glance, it might seem as if discourse on mental health has never been more openly discussed thanks to platforms such as TikTok, but in the words of Habermas (1991), the “world fashioned by the mass media is a public sphere in appearance only” (Habermas, 1991, 171, as cited in Fuchs, 2014); TikTok is still a capitalist medium that restricts the public sphere in several ways. For one, a significant part of mental health content on the platform is heavily commercialized. An example of this is a video posted by Ukrainian TikTokker Max Klymenko (figure 4). In the video, Klymenko argues how wearing certain colors could impact one’s mood and well-being. The arguments in the video, however, are quite misleading: while color can certainly “influence psychological functioning in a subtle non-conscious fashion” (Friedman & Förster, 2010, as cited in Elliot & Maier, 2014, p.109), these effects are a function of social learning and thus not as generally applicable as this video implies (Elliot & Maier, 2014). The caption of the video mentions that this is an advertisement as it contains the #ad hashtag, which is sponsored by the British fitness apparel brand Gymshark. As the video continues, Klymenko mentions several colors and their supposed effect while repeatedly changing into Gymshark clothing that matches the color he speaks about. There are many other examples of sponsored videos about mental health-related topics on TikTok, which present themselves as educational videos while in fact, they are advertisements in disguise.

Figure 4. TikTok by @maxklymenko

Such videos are often not fact-checked, meaning there is a high risk of spreading misinformation (Sung, 2021). This, however, is not to argue that all mental health-related content is misleading or created with a commercial purpose in mind. There are mental health experts, such as licensed therapists, who create TikTok videos that include scientific evidence to support their claims. Nevertheless, the commodity logic of TikTok as a platform makes it very difficult to distinguish reliable sources; the creators of mental health-related TikToks often use a similar video format because it is algorithmically “rewarded” by the platform (Kanevsky, n.d., as cited in Sung, 2021).

Issues of understanding and presence

Besides the commodification of mental health content, another risk of sharing such private discourses on a public platform such as TikTok is that it could affect our understanding of mental health disorders. As common symptoms become pathologized in mental health videos on TikTok, they are often presented without considering important contexts. For instance, not only do several mental health disorders exist on a spectrum, but there is also a possibility that some symptoms are part of an underlying physical health issue. As a result, many mental health disorders discussed on TikTok are prone to become stereotyped, oversimplified, and/or misunderstood (van Niekerk, n.d., as cited in Greig, 2021).

As common symptoms become pathologized in mental health videos on TikTok, they are often presented without considering important contexts

There seems to be a sort of countermovement consisting not only of the aforementioned mental health professionals who aim to combat misinformation but also of other content creators who attempt to raise awareness and/or educate and help others by sharing their personal journeys of living with a disorder (Pugle, 2021). In the latter case, however, some TikTok content creators become the targets of hateful and accusatory responses (Shepherd, 2021). This could be partly due to the fact that mental health content on TikTok is already so heavily commodified, and the numerous cases in which disorders were even faked by content creators for ‘clout’ – a term which can be understood as the ability to influence or, in the Bourdieuan (1986) sense, a form of social capital (Bourdieu, 1986, as cited in Tiffany, 2019). Mental health disorders seem to be ‘policed’ on the platform, with recipients judging whether the creator of the video is showing symptoms that are ‘genuine enough’, and whether they even have a real-life condition or not (Shepherd, 2021).

This antagonizing of some content creators on TikTok by other users may have something to do with issues of presence in, what Miller (2012) calls, “a contemporary culture in which social life is increasingly lived and experienced through networked digital communication technologies along the physical presence of co-present bodies” (Miller, 2012, p. 265). Miller argues that mediated presences, such as those occurring on TikTok, strengthen “our cultural tendency to objectify the social world and weaken our sense of moral and ethical responsibility towards others” (Miller, 2012, p. 265). Our online interactions cannot convey the same kind of ethical responsiveness as interactions during which we are physically present with each other. The hateful, policing responses targeted to content creators that discuss their own mental health disorders on TikTok illustrate this ethical separation. Additionally, much of the software we communicate through with each other cannot adequately convey human expression; digital technology decides how we communicate and can thus be revealed in this online sphere (Miller, 2012). This can also be seen, for instance, in the video format that so many content creators use when discussing mental health because it is rewarded by the TikTok algorithm.

Social life thus becomes objectified and instrumentalized in a process that Heidegger (1977) referred to as ‘Enframing’ (Heidegger, 1977, as cited in Miller, 2012). As Miller (2012) put it, Heidegger argued that “metaphysical presence and technological ways of being create a nihilism in which the only meaning or worth the things of the world possess is how they can be used or exploited” (Miller, 2012, p. 274). This exploitation can be clearly seen in the already mentioned commodification of mental health content on TikTok.

Ultimately, while mental health-related topics are openly discussed through TikTok videos, their commodification and objectification may perhaps only reinforce the misunderstanding and social stigma that surrounds mental health disorders, which, in turn, negatively impacts those who are already suffering from real-life conditions (Iardino, Sacchi, Massari, Iardino, & Brogonzoli, 2021).

Self-diagnosis is not the enemy

Some argue that the widespread phenomenon of self-diagnosing that comes with the mental health content on TikTok is due to a trending eagerness to view our behavior through a medical lens (Greig, 2021), or a desire to be different and unique – especially among teenagers (Mellor, 2021). While there are certainly dangers to self-diagnosing on TikTok, especially in light of the aforementioned misinformation that such videos are prone to spread, it can also pose as a helpful tool for those who do not have access to affordable health care. Arguing that self-diagnosing based on social media content is merely dangerous would be inconsiderate to the real-life experiences of those who do not have access to medical diagnoses (Weatherley, n.d., as cited in Porteous-Sebouhian, 2021). Self-diagnosing has even helped many individuals in seeking therapy or other professional help (Warner, 2021).

Arguing that self-diagnosing based on social media content is merely dangerous would be inconsiderate to the real-life experiences of those who do not have access to medical diagnoses

Additionally, digital platforms such as TikTok offer individuals a highly accessible space to consume information about mental health-related topics. The way these topics become objectified, instrumentalized – and perhaps also categorized – in the Enframing process occurring in this online sphere also allows individuals to more easily access certain communities that they physically might not have been able to access as easily (Moskowitz, n.d., as cited in Greig, 2021). The quality of social interactions in such online communities, however, is also influenced by a sense of overwhelm that our increasingly networked society has brought about. As Turkle (2011) argues, there is an ‘always on’ demand in which individuals are more and more distracted or absent “because of the continuous multitasking involved with immersion in ubiquitous digital communication technology” (Turkle, 2011, as cited in Miller, 2012, p. 270). As digital technologies, such as TikTok, are used to make our interactions more efficient and keep emotional distance, it becomes more difficult to overcome the earlier-mentioned ethical separation of our online interactions.

The diagnosis of self-diagnosis

The aim of this paper was to explore the risks of performing private discourses about mental health on TikTok. Content related to mental health is very popular on this platform, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic; because of this, such content tends to be heavily commodified and presented in a way that evokes a sense of relatability for as many individuals as possible. Partly because of this, a large number of individuals tend to diagnose themselves based on pathologized symptoms. As a consequence, mental health disorders are prone to be misunderstood and/or stereotyped.

Certainly, self-diagnosis can be an extremely useful tool for those without access to (affordable) health care. However, it can be extremely difficult to distinguish reliable sources on a platform such as TikTok. Furthermore, those who share their journey of living with a real-life condition often only grasp their unique, individual experiences which cannot necessarily be generalized.

Lastly, there is an issue of presence regarding these private discourses on TikTok; As there is an ethical separation between our online interactions and our physical ‘offline’ interactions, those who attempt to raise awareness about specific mental health disorders run the risk of receiving hateful comments and the policing of their real-life conditions.

References

Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2014). Color psychology: Effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning in humans. Annual review of psychology, 65, 95-120.

Fuchs, C. (2014). Social media and the public sphere. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 12(1), 57-101.

Greig, J. (2021, April 22). Why do we love to pathologise normal behavior online?

Iardino, R., Sacchi, M., Massari, E., Iardino, S., & Brogonzoli, L. (2021). “Ma sei fuori?”: a path to awareness on mental health and stigma. European Journal of Public Health, 31(Supplement_3), ckab165-574.

James, C. (2021). When mental health content leads to self-diagnosis, we’ve got a problem.

Mellor, S. (2021, September 4). 'Munchhausen by Internet’ and the dangers of self-diagnosing mental health issues on TikTok.

Miller, V. (2012). A crisis of presence: On-line culture and being in the world. Space and Polity, 16(3), 265-285.

Porteous-Sebouhian, B. (2021, October 1). How is TikTok changing the way young people relate to their mental health?

Pugle, M. (2021, September 1). The top mental health TikTok influencers – and why they’re important.

Shepherd, H. (2021, June 23). Is illness appropriation Tiktok’s most troubling trend?

Song, M. (2021, March 10). On TikTok, mental health creators are confused for therapists. That’s a serious problem.

Tiffany, K. (2019, December 23). Why kids online are chasing ‘clout’.

Warner, M. (2021, March 26). A challenge with social media: self-diagnosing mental health.