Cardboard and Old Glory: reading protest signs at the demonstrations against Trump’s travel ban

What do protest signs tell us about social movements and their supporters? An analysis of protest signs in response to President Trump's travel ban.

The power of linguistic landscapes

Language is powerful. It is not only a tool to convey a message, but also to inspire and mobilize, having the capacity to create change—there is much to be learned about a given community by observing its use of language. Public spaces speak directly of the population inhabiting or occupying them. The “visible bits of written language”, and where they occur are known as linguistic landscapes. Blommaert (2013) welcomes this development in the field of sociolinguistics because it is diagnostic, enhances realism, calls attention to literacy, and can “historicize sociolinguistic analysis”. Most frequently studied linguistic landscapes are those occurring in the “late-modern, globalized city” due to the inherent diversity existing there—ultimately, communities create linguistic landscapes, and linguistic landscapes have the power to shape communities.

Although traditional linguistic landscape material usually consist of fixed snapshots of text in a given space, this paper will explore a more mobile and temporary form of linguistic landscapes: signs at social protests. The community in question is thereby defined as the people who congregate in the place of protestation. By analyzing the language and images displayed and promoted on social protest signs and in the sphere of demonstration, a better understanding of social movements and their supporters can be achieved. Obviously, no protest was born out of contentment; the act itself exemplifies a facet of society that needs improvement. As sociolinguist Ben Rampton (2015) reflects in an interview: “If you can figure out how things tick in everyday practice, then you’ve got a better chance of intervening and changing everyday social life for the better.”

Protests in response to Trump’s Executive Order 13769

Since the election of Donald J. Trump for president of the United States, millions of people have gathered to protest against the administration for one thing or another. The ongoing mass demonstrations have been so present in American current events, there is even a specific Wikipedia page to chronologically keep track of the chaos: Timeline of Protests against Donald Trump.

Immediately after his victory in early November 2016, people mobilized in objection all across the country. Months later, citizens remained in disgust and protested Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017. The following day, January 21, 2017, marks the largest protest in American history: the Women’s March, where women and men of all ages gathered to advocate for women’s and other human rights issues (Waddell, 2017). Other protests following Trump’s election included the Not My President Day—ironically and cleverly—held on U.S. President’s Day; the Day without Immigrants, to show disagreement with the administration’s views on immigration; and the People’s Climate March, in opposition to the new president’s environmental policies (“Protests against Donald Trump,” n.d.). One of the most interesting protests occurred in immediate response to Executive Order 13769, otherwise known as the “travel ban”.

The travel ban is a curious case study for sociolinguistics because from the start there was a discrepancy in the title of the decree itself. Essentially, the order did indeed ban travel: it was designed to “keep refugees from entering the country for 120 days and immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim nations out for three months. The countries affected are Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Libya, Yemen and Somalia” (Criss, 2017). To whom it banned travel was the reason the mass public and the media dubbed it as the “Muslim ban”, though the Trump administration was quick to dispute these claims. Whether the insinuation is accurate or not, adopting and endorsing such a title has serious social consequences. In a country that was founded on the principle of religious freedom, naming an executive order this way could provoke American Muslims to feel like unwanted intruders in their own country, a self-fulfilling racist depiction of the president, and a widening divide between the political left and right.

Social protests are normally ‘grassroots’: they are a bottom-up reaction to a top-down influence. The signs, props, and accompaniments, subsequently are grassroots (i.e., low production-quality, usually homemade). Despite the lack of professional quality, some signs at the Trump travel ban protests were creative, provocative, and noteworthy. The overall theme conveyed in the protest signs was mostly in opposition to the travel ban itself; however, different facets included pro-Muslim support, anti-Trump ideology, and national solidarity. There was various rhetoric used in the protest signs. Language was used as a means to argue, to make a point, to poke fun, and/or to show kindness and support to the people targeted by the ban. The intended audiences are also an interesting factor; some signs were meant for the refugees and people affected by the ban, others were directed at the Trump administration, and various were displayed for fellow Americans just to take notice.

Data collection and analysis

In the following sections, I aim to investigate the linguistic landscape(s) of some of the protests in response to Trump’s Executive Order 13769, while exploring different ways the travel ban gave rise to written language in public space? more specifically, how did these social protest signs make meaning As Blommaert (2013) suggests, it will be a study “aimed at identifying the fine fabric of their structure and function in constant interaction with several layers of context” (p. 20).

Protests following the Trump travel ban occurred all over the United States: in the downtowns in major cities, central parks, and most appropriately, inside and outside airports where people were being detained. Word of the demonstrations caught on quickly, grew rapidly, and were documented immediately, thanks to the digital age and what Castells (2013) calls a ‘networked social movement’. The events naturally gained media attention, and participants and onlookers photographed, videoed, and posted about the happenings in real time. The images gathered for this paper were retrieved online through news and social media articles portraying the events. One could consider the several articles portraying the events (see appendix 1) as an ‘online’ linguistic landscape in and of itself. However, the analysis of the signs in this paper will come from the viewpoint of the original location, where the protest took place.

By design, social protests include an immensity of written language—albeit temporary—in a confined public space; this leads to a rich linguistic landscape with excessive data. The signs included in this analysis are not an exhaustive collection of the diverse signs used at the Trump travel ban protests. However, they do provide a microscopic look into some examples of “serious” signs (i.e. neither sarcastic nor humorous) that vary in visual-presentation complexity and production quality.

The protest signs will be analyzed by their physical appearance as well as their semiotic content; these criteria will be used to help understand the overall manner in which the signs make meaning. The following analytical categories will be used: presentation (what the sign looks like), audience (who is it intended for), intertextuality (what other things it refers to), indexicality (what features on the sign point to something else in the way it is semiotically composed), and theme (what is the message). As a further explaination indexicality, Blommaert (2013) says: “Every sign tells a story about who produced it, and about who is selected to consume it. In that sense, every sign points backwards 54 to its origins, and forward to its addressees” (p. 53).

Examinations of three protest signs

Classic Cardboard

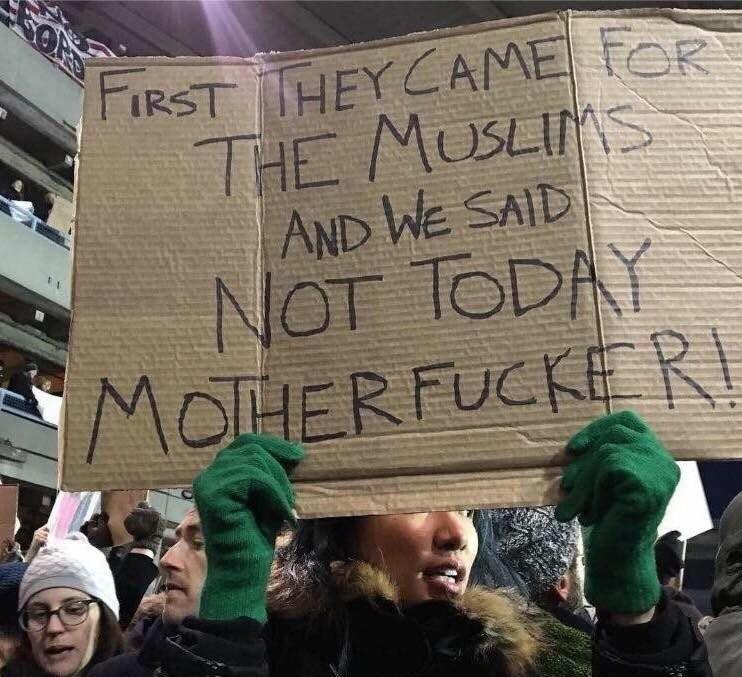

The sign in Figure 1 is simple in its presentation: permanent marker on a piece of cardboard. Possibly the most classic protest sign, the minimal effort and low production quality conveys a sense of haste. The importance evoked is less on the creativity, and more on the urgency to physically join the movement.

Figure 1 - 'First They Came' (photo taken at LAX in Los Angeles, California)

Figure 1 demonstrates the effectiveness of minimalism. The sign reads: “FIRST THEY CAME FOR THE MUSLIMS AND WE SAID NOT TODAY MOTHER FUCKER.” Though visually simple, it packs a powerful semiotic punch with its brute language and intertextuality. The use of capital letters has been known to indicate ‘shouting’ in written speech; this, along with the words ‘mother fucker’ and the exclamation mark, suggest a high level of anger and discontent.

Although the text is in the form of a story and includes the phrase “we said”, the intended statement after the phrase lacks quotation marks. The absence of this punctuation could suggest a slight incompetence of written language, since use of quotation marks is a Standard-English grammar rule for writing quoted speech. However, the omission could have been intentional, therefore giving an additional “Fuck you!” to the establishment or perhaps even to normativity.

The intended audience is a bit convoluted: the last segment, “not today mother fucker” is assumed to be intended for the Trump administration. However, the fact that the text is in the form of a story—using the words “first” and “we said”—leads readers to assume that the sign was meant for fellow protesters or fellow Americans. Using the word “we” creates solidarity among the protesters, indicating that they are in the fight together against the other group, the administration, specified by use of the word “they”. Thus, the sign has two perceived audiences: the Trump administration and companion protesters.

The intertextuality of this sign is so significant that the influential text it goes back to was nicknamed “The Poem of the Protests” in an article. The original circa-1950s text is that of the German theologist Martin Niemöller and was a mention to the Holocaust. The poem (depicted below) was actually about the fact that the intellectuals did not protest, and exhibits the consequences of indifference.

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

While the poem was originally written in German, the English translation was widely circulated on social media during the divisive presidential election. The historic text is applicable in modern day times and may have been used as “a warning about the ease with which such an event could occur again, if we of the present allow ourselves to become ignorant of the lessons of the past” (Garber, 2017). What is interesting in the Figure 1 sign is that the creator changes the narrative; she declares that the people do indeed speak out, by the use of the “not today mother fucker” phrase. Perhaps she is validating her efforts of protestation. Whatever the case, including such a strong text that is linked with a tragic event, the sign creator wants to show her perception of the severity of the situation.

On a note of indexicality, we can choose to conclude that the sign creator is well-educated and culturally aware of socio-political happenings, history, and political literature because of her effective use of Niemöller’s text on her protest sign.

This sign makes itself meaningful by its strong language, rustic look, and straightforwardness. Its rhetoric is serious in nature, but romantically and cunningly supported with the intertextuality of the poem, cautioning us of the dangers of “political apathy” (Garber, 2017). The theme for this sign includes three aspects: discontentment with the administration, support for the Muslim community, and promotion of solidarity—conceivably both nationally and within the protest-community. The message is clear: the Trump administration will not get away with this act, and that the people will not stand idly by and let such a challenge to foundational American values to occur.

Protest Sign Print

Moving away from traditional handwritten protest signs, which has a semiotic effect of authenticity, some people opted for prints. Figure 2 shows a protest sign with a now-familiar illustration of a Muslim woman using the American flag as her hijab—a traditional religious headscarf. Although this image can be seen in many photographs of Trump protests (see Appendix 1), this sign was used at New York City’s JFK airport on January 28, 2017 following the travel ban executive order. Instead of a printed-out homemade sign made on the computer, this is an actual piece of art that was created by illustrator Shepard Fairely for protest purposes. The composition is readily available to print, free of charge, and was commissioned by the Amplifier Foundation (Lum, 2017). The foundation says, “Today we are in a very different moment, one that requires new images that reject the hate, fear, and open racism that were normalized during the 2016 presidential campaign” (Amplifier Kickstarter Campaign, Lum, 2017).

Figure 2 - 'We the People' (photo taken in New York City, NY)

Although this is a 'linguistic' landscape analysis, image plays a decisive role on this protest prop. The portrait on the sign can be appreciated as a beautiful piece of art. It oozes patriotism, and the colors are complementary and earnest. (One might recognize the color-scheme and style index that of the 2008 Obama campaign posters: Fairely was the same artist.) The Muslim woman using the American flag as a hijab symbolically portrays it as a protective blanket of inclusion. She is a good-looking woman with made-up eyes, red-painted lips, sharply drawn eyebrows, a symmetrical face, and high cheek bones—all indicators of the laws of attraction (Pronk, 2017). Her eyes grab your attention, and you could quickly forget you are looking at a protest sign.

But why the depiction of such attractiveness? In traditional Islamic religion, make up is actually not encouraged, and modesty is promoted (Al-Ahmed, 2010). The whole point of using a hijab and covering oneself is to do the exact opposite: to diminish attention. So here, on this work, we see a cultural paradox between the function of the protest sign and the essence of the religious community the protestors are fighting for. However, it is unlikely that the user of the sign considered this while choosing to use this free picture, conveniently found online.

Although the production quality is rather high (printed out in full-color), the assembly lessens this status a bit: it is glued on a recycled paper towel roll. This could indicate “protest on a budget” and insinuate haste, as in Figure 1. The idea of using whatever means necessary to slap together a sign (so the protestor can get out to join the movement) is conveyed, again.

The text on the sign is almost an afterthought, being secondarily noticed after seeing the artistic picture. Though modest in size and only taking up a small fraction of the sign space, the words are powerful. It reads on the top line: “WE THE PEOPLE”, and on the bottom line: “ARE GREATER THAN FEAR”. The mention of “we” signifies unity and togetherness, but stands among a strong, intertextual phrase, not unlike that in Figure 1. The three words are well-known in American culture, as they comprise the initial phrase of the United States’ Constitution. The historic and iconic “we the people” phrase is also written larger than the rest of the text, and is situated above all other writing.

Example of the introductory text on the U.S. constitution

Including these words in this mirrored way strikes yet another patriotic tone. They announce to the observer that the audience for this sign is undoubtedly the American people. accompaniment of the image highlights to Muslims that this means them too, that they are included in the “we” group. The bottom phrase, “are greater than fear,” further emphasizes solidarity and possibly insinuates power in numbers by the use of the comparative phrase. It has a positive connotation, and the message is that “we” will overcome this hardship and oppression that is now manifesting as the travel ban.

The eye-catching beauty and professional graphic-design style of this sign helps it to make meaning. The original illustrator consciously made this sign to be symbolic of the adversity that the American people face nowadays, and it has become an image frequented at demonstrations and online. The theme is clear: solidarity will prevail. However, we know that the user of the sign in Figure 2 had little input into the actual creation of the sign. The attractiveness caught his or her attention, and the print out was effortlessly assembled onto an empty roll.

A Paper-Alternative Creation

Unlike the previous two signs, in the last example (Figure 3) I will focus on entails a bit more creativity from the sign maker. Going out of the box, this woman selected an American flag as her sign’s media, writing directly onto the fabric with black permanent marker. She used the white stripes of the flag and wrote neatly in the space provided, reminiscent of a school teacher’s calligraphy.

Figure 3 - 'New Colossus' (photo taken in Los Angeles, California)

The carefully executed script, on a crisp, clean national flag, denotes the elite quality of this protest sign. As in Figure 2, this protester also uses the American flag as a platform to be heard and noticed. The ‘courage’ and pride with which the sign creator displays her work is noteworthy, since writing on a flag could be seen as desecration and taboo. Nonetheless, use of the banner is an obvious choice for a sociopolitical demonstration. A nation’s flag has significant weight and can be seen as an institution itself. It outlives political discourse and fighting, and is apolitical yet patriotic.

The audience here differs from the previous two examples in that there is no explicit message for the Trump administration. This may index “taking the high road” or a refusal of pettiness amidst a climate of political immaturity. The text is not overtly intended for the Muslim community, but rather, targets a more encompassing audience, seemingly speaking to all immigrants. The sign reads:

“GIVE ME YOUR TIRED, YOUR POOR, YOUR HUDDLED MASSES YEARNING TO BREATHE FREE. THE WRETCHED REFUSE OF YOUR TEEMING SHORE. SEND THESE, THE HOMELESS, TEMPEST-TOSSED TO ME…”

These words harbor patriotic intertextuality, as the text is that of the sonnet, "The New Colossus", which is inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, a classic American icon of hope and freedom. The poem by Emma Lazarus served then —like it does now—as an expression of the “plight of refugee immigrants” (poets.org). Because of the sign’s national symbolism, we can infer that the display is also intended to spark attention and nostalgia from American citizens.

Similar to the inference made about Figure 1, use of such historically famous text on the protest sign indexes an awareness of America’s past. We could also assume that the sign maker is well-educated and fosters a decent understanding and/or appreciation of poetry. However, it is also possible that she merely discovered the text online, as she was not the only one to use these words. “Scrawled across signs and typed out in tweets, those opposing the Trump administration’s immigration and refugee policies have made Lazarus’s most famous words their rallying cry, proof, they say, that American liberty means welcoming those in need, not shunning them” (Mettler, 2017).

Depth of knowledge of the text aside, the creator chose to include it in her protest sign. The “New Colossus” poem written on the American flag exudes patriotism. Its audience choice maintains integrity, and the professional and careful execution of this sign mark it as elite.

Conclusion

The demonstrations occurring in the wake of Trump’s travel ban were exemplary of digital-age protests. The protest signs analyzed were chosen because of their popular content. While collecting data online, the “First they came” poem, the image of the Muslim woman wearing the American flag headscarf, and the “New Colossus” text were highly reoccurring material.

We can attribute the invariability of semiotic content to the fact that this a ‘networked social movement’. Many of the ideas were produced, shared, and encouraged on the internet in articles like 13 Ideas to Protest the Refugee Ban. In these modern protests, “the movement can develop largely in the digital world, while simultaneously the meaning of urban space is constructed by the empowered individuals participating” (Chuen Ng), therefore giving rise to an interconnected linguistic landscape. Although perhaps giving way to a lack of creativity and innovation, the modern way of sharing and accessing protest-sign ideas promotes uniformity in demonstrations occurring geographically far away from each other, which further strengthens solidarity.

All three examplesincorporated historic text onto their protest signs. Intertextuality is clearly crucial, and social activists have long highlighted tribulations of the past. Since “history gives you a much broader palate of what’s possible” (Snyder, 2017), it’s obvious why protestors chose to resuscitate the texts and give a nod to previous eras.

Coupled with the ‘networked social movement’, emphasizing the ease at which information and content was shared, it makes one wonder if the sign creators genuinely used the historically powerful text, or if it was just an assembly forged on commodity. For further research, it would be interesting to investigate background information and the motives of the sign creators themselves in order to find out if the texts were actually part of their intellectual repertoires, or if they were simply added to the sign because it was ‘trendy’ to do so.

The Trump travel ban gave rise to a plethora of written language in many locations worldwide. This paper accentuated three examples of historic written text that was transformed and used for protest purposes. The texts made meaning on the signs with their various accompanying factors: target audience, language used, presentation, and intertextuality. The underlying indexicality insinuated haste to participate in the protest event, possible lack of creativity, and points to a networked social movement. Lastly, it’s possible to conclude global features of protests in linguistic landscapes, namely the incorporation of historic texts and the use of national flags as platforms to communicate an idea.

Protest signs, like the ones examined here, are an important component of modern activism. It is logical to expect these key components will influence the linguistic landscape in which they are present, as we continue to witness protests in the digital age. Again, we see that communities create linguistic landscapes and linguistic landscapes have the power to shape communities.

References

Al-Ahmed, R. (2010). Makeup and the Hijab: A Study with Seven Muslim Women Explores Possible Contradictions. The Qudosi Chronicles. Retreived from http://muslimreformers.com/2010/08/09/makeup-and-the-hijab-a-study-with-seven-muslim-women-explores-possible-contradictions/

Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvtilburg-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1372129

Castells, M. (2013). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. Malden: John Wiley & Sons.

Chuen Ng, Ho (2016, March 13). The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong: Social movements in the digital age. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.diggitmagazine.com/papers/social-movements-digital-age

Criss, D. (2017, January 20). Trump Travel Ban: Here’s what you need to know. CNN. Retreived April 20, 2017, from http://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/30/politics/trump-travel-ban-q-and-a/

Mettler, K. (2017, February 1). ‘Give me your tired, your poor’: The story of poet and refugee advocate Emma Lazarus. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/02/01/give-us-your-tired-your-poor-the-story-of-poet-and-refugee-advocate-emma-lazarus/?utm_term=.ee674e7ceee3

Pronk, T. (2017, February 14). Introducing the Netherlands-Universal Love and Attraction [Seminar]. Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands.

Protests against Donald Trump. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved April 20, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protests_against_Donald_Trump

Rampton, B. (2015, January 15). Sociolinguistics [Video file]. KingsCollegeLondon. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42Q6-pQXkzU

Snyder, T. (Interviewee). (2017, May 30). Waking Up with Sam Harris [Audio Podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.samharris.org/podcast/item/the-road-to-tyranny

Waddell, K. (2017, January 23). The exhausting work of tallying America's largest protest. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/01/womens-march-protest-count/514166/

Appendix 1: Articles documenting the travel ban protest signs

All the best protest signs from the weekend of Muslim ban demonstrations 1-30-17

The Best (& Most Savage) Signs From This Weekend's Protests 1-30-17

The 35 Absolute Best Signs Supporting Muslims at the #NoBan Protests 1-30-17

All the best protest signs from the weekend of Muslim ban demonstrations 1-30-17

These Are the #MuslimBan Protest Signs Everyone Needs to Read 1-30-17

19 Inspiring Signs Protesting the Immigration Ban from Across the U.S. 1-30-17

The best signs from protests over Donald Trump's immigration ban 1-31-17

The 26 best signs from last night's protests against Trump's 'Muslim ban' 1-31-17

11 hilarious protest signs about the Muslim Ban 2-1-17

Trump Immigration Order Triggers Protests Across US 3-19-17