Blinkist: Solving for Reading in the Attention Economy?

Blinkist is an app developed by a software company in Berlin. According to its marketing campaign, it “makes reading books realistic again”. But what kind of reading does it facilitate, and is this really what we, hardworking scholars and students, need in our spare time? I tried the app for a week and reflect on the pros and cons.

Let’s be honest. Who has the time to read these days? How often do you find yourself settling down with a book instead of opting for Netflix, broadcast television, a videogame or a magazine? In the 1980s and 90s, predicting the death of books was a popular activity, ruled by a logic that Henry Jenkins (2006) called the ‘digital revolution paradigm’, the notion that new media absorb the functions of old media, and that the Internet would devour all. Whereas these predictions turned out to be wrong, I often find myself opting for less intensive, more dispersed forms of entertainment.

It’s a smart marketing ploy: to acknowledge the challenge of ‘fitting’ reading into your life, to make explicit how books compete with other media and forms of leisure in an attention economy, and cater the solution explicitly to ‘the thinking person’.

In our current attention economy, where attention is quantified and monetized in a world saturated with media, it is not surprising that we often choose more fast-paced and immediately rewarding activities over the time-consuming act of close or ‘deep’ reading. I need to know if the hype is justified around the latest Netflix series everyone is talking about, what if I’m the only one without an opinion in my next social gathering on Zoom? Meanwhile, the sight of the ever-growing pile of books on my nightstand induces guilt. Especially in these times of crisis that, as everyone keeps saying, should inspire reflection and slowing down, thinking about things that really matter. Will I remember this quirky FMV detective game I played? Would it get a mention in my imaginary autobiography?

App for intellectuals

As if the Internet knows about my predicament (probably because it’s near-universal), it kept serving me these Blinkist ads which offer to help me, as “an intellectual”, “fit reading into [my] life”. Already I feel less ashamed: apparently, not reading is a sign of intellectualism! It’s a smart marketing ploy: to acknowledge the challenge of ‘fitting’ reading into your life, to make explicit how books compete with other media and forms of leisure in an attention economy, and cater the solution explicitly to ‘the thinking person’.

Blinkist promises to solve the problem of reading in the information age for us without necessitating a lifestyle change. It has distilled the “key takeaways” of 3000+ non-fiction books ranging over a number of categories such as science, productivity, sex, personal development, and parenthood. For 6,67 euro a month you get a premium account with unlimited access, a Kindle connection and synchronization with Evernote. A more basic version without these bonuses costs 4,17 euro a month. These summaries of the main points have a duration of about 15 minutes, to read or listen to in one go, or in smaller ‘blinks’ if you don’t have even that kind of time to spare.

Doesn’t everything worth knowing or experiencing ask for at least a bit of effort, just a smidge of resistance? Shouldn’t you have to work for what’s interesting? Or are these old-fashioned ideas my teachers have put in my head, useless in our present society and media scape?

Each blink opens with: “What’s in it for me?”—which tells us something about the concept of reading underlying the app. It’s an activity with a clear goal. It yields a calculable profit. This makes it a perfect ‘life hack’ for the attention economy. Reading Blinkist is very much ‘on demand’. You can pick your time and place, and if you use the audio files, you don’t even need to use your hands. Now I can utilize those ‘lost moments’ when doing the dishes or putting on makeup, and fill them with new knowledge.

The Burden of Self-improvement

It is a typical expectation for our neoliberal society: getting informed as a personal responsibility, and as part of an always-ongoing process of self-improvement and -enhancement. I could already picture myself going on a date and churning out all these interesting factoids about fishing or stocks or how wine is made, to seem up-to-speed on a topic the other is invested in. It feels a bit like cheating, making it too easy. Doesn’t everything worth knowing or experiencing ask for at least a bit of effort, of resistance? Shouldn’t you have to work for what’s interesting? Or are these old-fashioned ideas my teachers have put in my head, useless in our present society and media scape as they only slow us down?

Evgeny Morozov’s (2013) term ‘solutionism’ comes to mind: the idea that technology can solve all of our problems, including those we didn’t know existed before we had the technology to solve them, and those that were caused by technology in the first place. Think of productivity apps that render other apps and websites temporarily inaccessible, or indeed, apps to ‘solve’ our lack of time for reading. Morozov describes such solutionist inventions as part of a cultural drive to eradicate imperfection and make all aspects of life run smoothly.

It has to be noted that the idea of reading that underlies apps like Blinkist is quite limited. It only touches upon a small part of what reading is and does: abstracting information, distilling knowledge from a source in the most efficient and effortless way. However, even non-fiction books are not pure information, certainly not the kinds I like to read. How do they decide what is important enough for the 15-minute version? How to summarize someone’s biography for instance? We can’t always know beforehand what might turn out to be important or valuable in a book, and it might be something different for you than for me.

Slower & Deeper

As a reaction to the fast-paced attention economy, the last years have witnessed an upsurge in the publication of books promoting slow reading, the deliberate reduction of reading speed. These include John Miedema’s Slow Reading (2009), Alan Jacobs’ The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction (2011), and Carl Honoré’s In Praise of Slow (2004). Slow reading has clear benefits: it involves higher-level cognitive processes like reflection and evaluation, and increases pleasure (studies show that we automatically slow down when reading the pages we value most). According to Philip Pullman, slow reading is a democratic act: taking control of your own reading pace is a form of personal freedom, and furthers an appreciation for democracy, as you are active in the process and in charge of your own time. David L. Ulin decribes slow reading’s counter-cultural potential in The Lost Art of Reading (2010) as “an act of resistance in a landscape of distraction, a matter of engagement in a society that seems to want nothing more than for us to disengage” (150). Sustained effort, slowing down, attention, and memory all seem to be correlated positively.

The reason that so many books have appeared about the topic of slow or deep reading, is that it is under threat. If our dominant media facilitate processes that are fast-paced, oriented towards multitasking and geared to big volumes of information, some psychologists and pedagogues fear, our reading circuit will follow suit. They anticipate that less attention and time will be devoted to the time-consuming ‘deep reading’ processes like inference, critical analysis, and empathy. Building memory and storing background knowledge are other important elements of the reading experience that simply take time.

Developmental psychologist and neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf is one of these scholars who fear we are losing the ‘cognitive patience’ required to read texts of a certain length. In Proust and the Squid (also available on Blinkist!), she describes the importance of detours and mind wandering in processes of deep reading: “Reading is a neuronally and intellectually circuitous act, enriched as much by the unpredictable indirections of a reader’s inferences and thoughts, as by the direct message from the eye to the text (16). The truly transformative part of the deep reading experience, according to Wolf, lies in how it incites us to go “beyond the author’s ideas to thoughts that are increasingly autonomous, transformative, and ultimately independent of the written text” (17-8). Written language is generative of new ideas beyond the letters on the page. To that extent, reading is a productive, creative act.

When we talk about the future of reading, those might be the more important experiences, and the ones we need to try to maintain. Apps like Blinkist will obviously not replace that kind of reading. Sometimes, the most meaningful and memorable experiences are not on demand (the Stones knew it all along: you can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, etc).

How to Do Nothing... in 7 Blinks

All this is not to say, however, that I don’t see certain merits in apps like Blinkist. There is definitely creativity involved here as well, but it resides in the making of the blinks, as the anonymous authors meet the challenging task to summarize the book while preserving the general tone, without repeating any of the original phrasings, for copyright reasons.

In some cases, the result can be disappointing compared to the real books, as Sian Cain wrote in The Guardian. Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time works surprisingly well in 21 minutes; Becoming by Michelle Obama in 19 minutes doesn't hold up (reasonably, it took a bit longer for her to become). During the free trial week I spent (mostly) listening, I had some solid fun with classics like Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom, Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, and The Laws of Thermodynamics by Peter Atkins. A title that was so beautifully paraphrased that I bought the full book immediately after (and that I probably wouldn't have bought otherwise), was Know My Name: A Memoir by Chanel Millen.

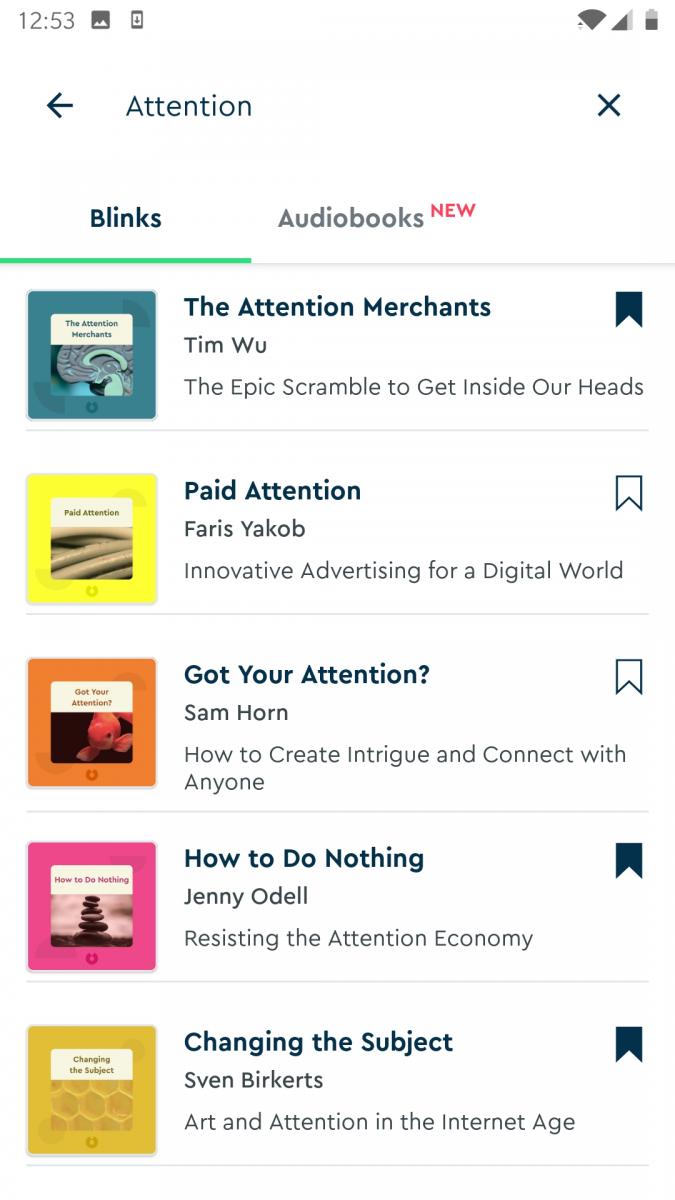

As I am interested in the phenomenon of attention, I stumbled upon some particularly ironic choices of books to consume in curtailed form, like How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell, Or Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age by Sven Birkerts. The poor guy is paraphrased as saying: “easily digestible information makes our experiences less gratifying and our lives less meaningful”. That made me chuckle: the ever-grouchy Birkerts would obviously not approve of what I was doing.

Mastering information overload

As easy as it is to criticize from the perspective of slowing down and deep reading, the app is obviously fulfilling a need: 11 million people currently subscribe to it, spending about 100 euros a year each. I can see why. In our times of overload, Blinkist offers a stylized, well-designed environment where thousands of books are selected, curated, and algorithmically catered to our own personal interest. It features a daily updated curator’s list of recommendations. There is the appealing and even slightly addictive effect of mass, of quantity, of accumulating more and more knowledge. The sheer act of bookmarking blink after blink as ‘read’ makes me feel a certain mastery over informational excess that is lacking when I randomly read and watch content online with nothing to show for it.

Plus, any way to motivate readers to pick up a book is welcome. Reading was never one thing or even binary (close/hyper, or deep/surface): it was always plural, with different modes for different tasks and types of sources. Hyperreading, computer-assisted reading, and speed reading will allow us to quickly get to the gist of information. Yet, close or deep reading is needed to critically engage with the meaning of texts. Vital skills for training informed citizens in democratic societies—especially in times overload, filter bubbles, fake news and post-truth.

It would be futile to pretend to be able to go back to ‘single-focus’ forms of input like books and leave digital media and task switching behind. Further, I think it is misguided to think that all serious reading must be undertaken in a cognitive mode of unbreakable attention. Given the length of anything longer than a haiku, reading always requires strategically allocating attention to text that seems more important at the expense of text seeming less important. In the case of Blinkist, we could say this task has been outsourced to professionals. One of my goals in research is to think of ways to integrate hyperreading with the most valued properties of close reading and deep attention. In the mean time, I’m happy to farm out some of the selection and curation of my reading-for-information to the expert writers at Blinkist. Maybe I can use the time that this opens up to slowly read and reread some of my favorite books of prose and poetry. Or maybe even do nothing once in a while.

References

Honoré, Carl. In Praise of Slow: How a Worldwide Movement is Changing the Cult of Speed. London: Orion, 2004.

Jacobs, Alan. The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York UP, 2006.

Miedema, John. Slow Reading. Sacramento, CA: Litwin, 2009.

Morozov, Evgeny. To Save Everything, Click Here. The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs, 2013.

Ulin, David L. The Lost Art of Reading: Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time. Seattle, WA: Sasquatch Books, 2010.

Wolf, Maryanne. Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.