Reusing Churches in the Netherlands

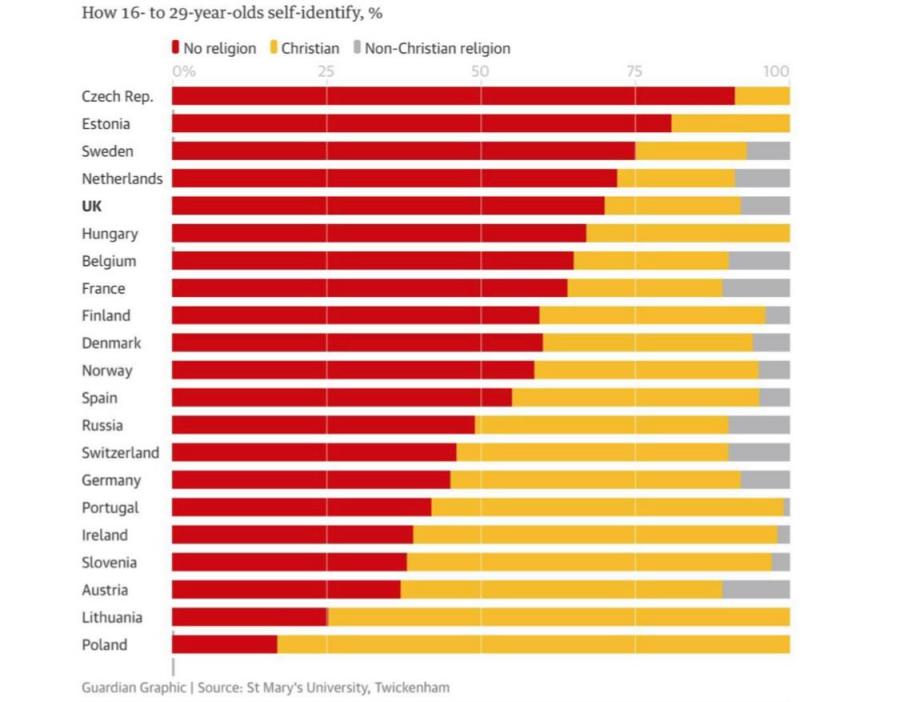

Religious involvement in the Netherlands has changed. “The seminal thinkers of the nineteenth century - Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud - all believed that religion would gradually fade in importance and cease to be significant...” (Norris, Inglehart, 2004, 2011). This is indeed true if we look at recent surveys which show that more and more young people in Western European countries perceive themselves as having no religion (see Figure 2).

However, contemporary projects that take place in churches prove that in times of weakening religion, churches still serve as a place of social gathering and remain the “totem” of society and a powerful center of communion.

Church Reorganizations

This article focuses on the Netherlands and researches what happens with churches that do not attract the same big numbers of believers anymore, and how they still function as places for social cohesion. The research on this topic is relevant because church reorganization projects keep growing year by year, as well as the attendance of such renewed spaces. This growing tendency is not just a trend, but an important marker for the position of religion in contemporary Western Europe.

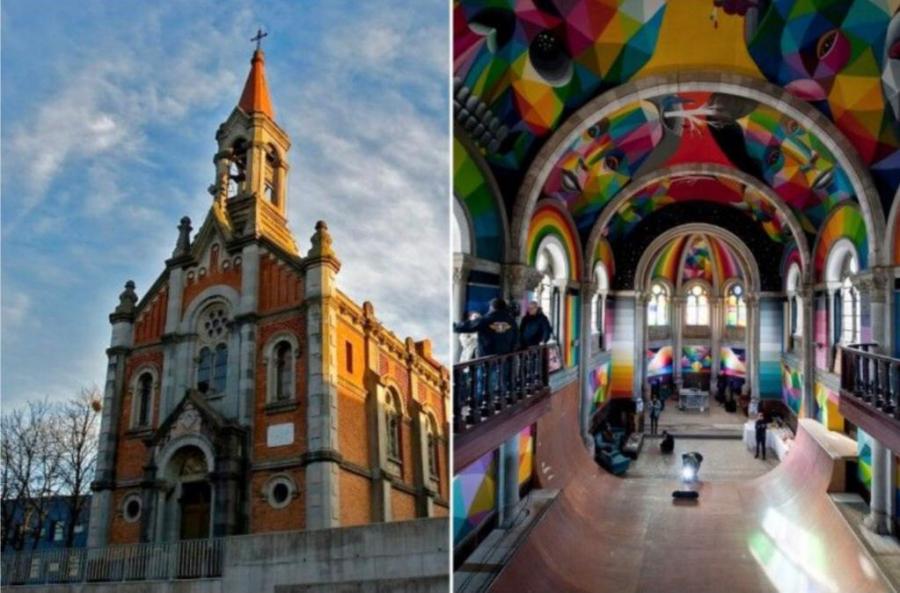

Figure 1: Church remade as a skatepark in Llanera, Asturias (Spain).

“The position of the church building is particularly paradoxical and ambiguous and an emotional issue” (Post, 2014). Churches have always been special places for Christian believers. “There is... the idea that all space is organized and oriented by the sacred place, itself regarded as the centre of man’s life, the point of reference around which his world is built, or, as it is vividly put in other traditions, the navel of the Earth” (Turner, 1979).

As the demand for the spiritual function of churches fades away due to the documented religious weakening, more reorganization projects appear across the world. The controversy around this phenomena keeps growing, separating the public sphere into two camps, those who support reuse and those who perceive churches as something that cannot be used in any other way. Through literature review and digital ethnography, I will analyze this phenomenon.

Why Churches close

The fact that reuse projects of church buildings occur is a sign of cultural change and a new attitudes towards religion. It shows the change in mindset of recent generations. “The position of church building is under a great deal of pressure - and that is true all over Europe...” (Post, 2014). The history of religion in Western Europe has obviously had its ups and downs, “one might argue more accurately that the Enlightenment philosophers were hostile to institutionalised Christianity, specifically the Roman Catholic Church, rather than to religion per se” (Turner, 2011).

It could be the case that the decline of religious beliefs is connected to historical circumstances of the recent centuries, “...ever since the Age of Enlightenment, leading figures in philosophy, anthropology, and psychology have postulated that theological superstitions, symbolic liturgical rituals, and sacred practices are the product from the past that will be outgrown in the modern era” (Norris, Inglehart, 2004, 2011).

Western European society has been building wealth and economic stability throughout recent decades, and it is proven that “...people who experience ego-tropic risks during their formative years (posing direct threat to themselves and their family members) or socio-tropic risks (threatening their community) tend to be far more religious than those who grow up under safer, comfortable, and more predictable conditions” (Norris, Inglehart, 2004, 2011).

Figure 2: How young Europeans identify their religion.

Churches are closing down more often because of the small number of parishioners and a lack of money to maintain the often monumental buildings. “Church buildings are becoming more and more superfluous and a heavy burden: they account for most of the costs and expenses faced by Christian communities” (Post, 2014). Recent research in the Netherlands shows that the number of people who occasionally go to church halved since 1970 (De Hart, 2014). This directly influences the need for church buildings in society. “Numerous inventories have been taken, and it is estimated that for instance in the Netherlands 1200 church buildings will have to be closed in the future. Current figures indicate that this amounts to about 100 per year” (Post, 2014).

Today, churches are more likely to be perceived as public locations for commemorations, weddings, and other religious or religious-like ceremonies. According to Archbishop Wim Eijk, “Over ten years the entire archdiocese of Utrecht will probably only consist of 10 to 15 churches that still hold the Eucharistic celebrations, compared to the current 280 churches” (NLTimes, 2018). What makes local authorities to keep the buildings is that many of them “...are listed as monuments, heritage sites protected by the state, which often automatically excludes demolition” (Pont, 2014).

There are alternative options as to what can be done to keep former church buildings functional, since “...church buildings are attracting a great deal of interest” (Post, 2014). It is no wonder that churches, which have been considered the locus of public life for decades, remaining so in the contemporary context. “They are landmarks, cherished as contributing to or defying a cityscape or the atmosphere of a village, they are treasured as a historical heritage, valued as a place of rest, a place for concerts” (Post, 2014).

Figure 3: Martin Garrix in Paradiso Amsterdam.

Church rebuilding projects in the Netherlands

The Netherlands has not escaped Europe's changes in religious climate. “Even in a country like Holland, famous for its liberal tradition, one in four of all the inhabitants attend church. Nevertheless, one assumption is true: most European churches attract fewer believers every year. Especially in the western part of the continent, the old religious institutions are deteriorating...” (European Value Studies, 2018).

Due to the recent changes in society, “with respect to policy discussions concerning the position of the church building in the Netherlands, a clear shift in interest can be seen around and after the turn of the millennium. The focus has shifted from renovation to the problem of vacancy and new uses for churches” (Post, 2014). Bars, skateparks, festivals, dance clubs, and bookshops - the list of the new opportunities for the church building usage can go on. In the Netherlands alone, almost every big city has a project involving the reuse of the church building.

Figure 4: Sold out at the concerts at Paradiso.

In Amsterdam, for example, there is a club and a music venue with the symbolical name “Paradiso” (Figures 3 and 4), which was used as a place for gathering by a religious Christian group until 1965. Since then it remains a place of regular music performances mainly for the youth. It has witnessed such well-known artists as Pink Floyd, Nirvana, The Rolling Stones, Madonna, etc., and is popular worldwide.

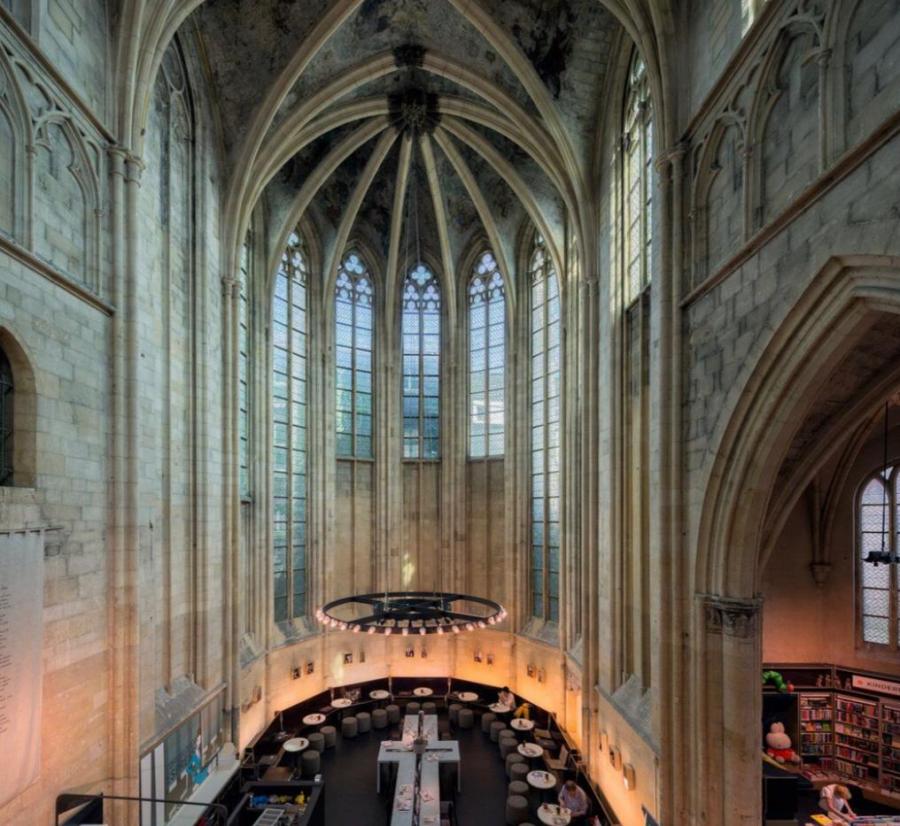

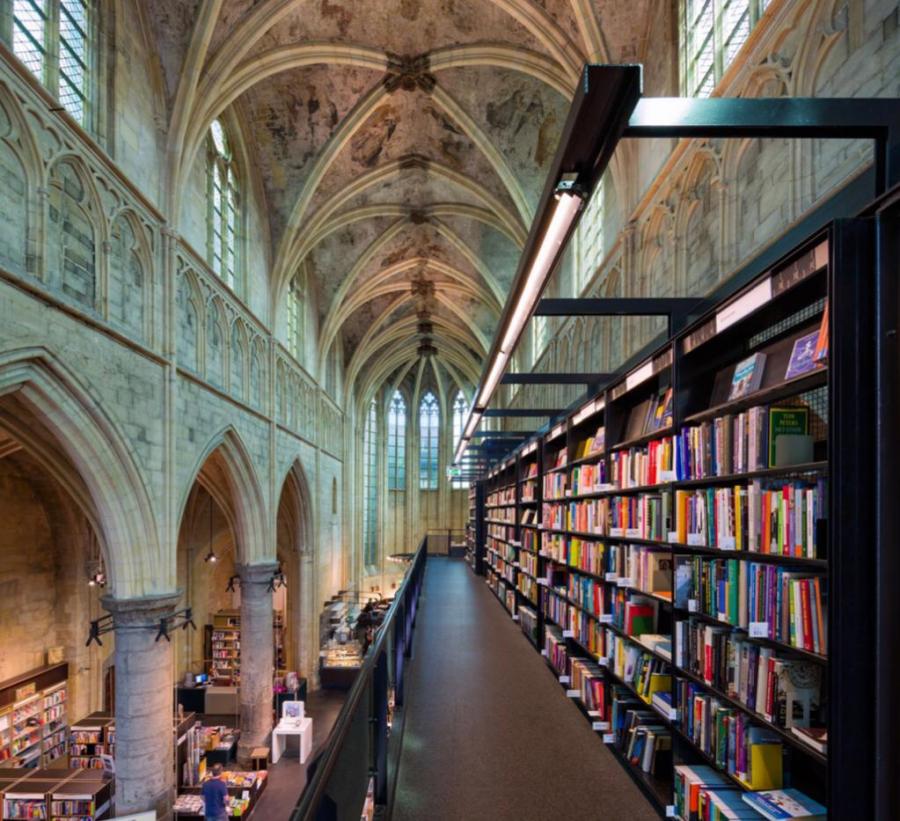

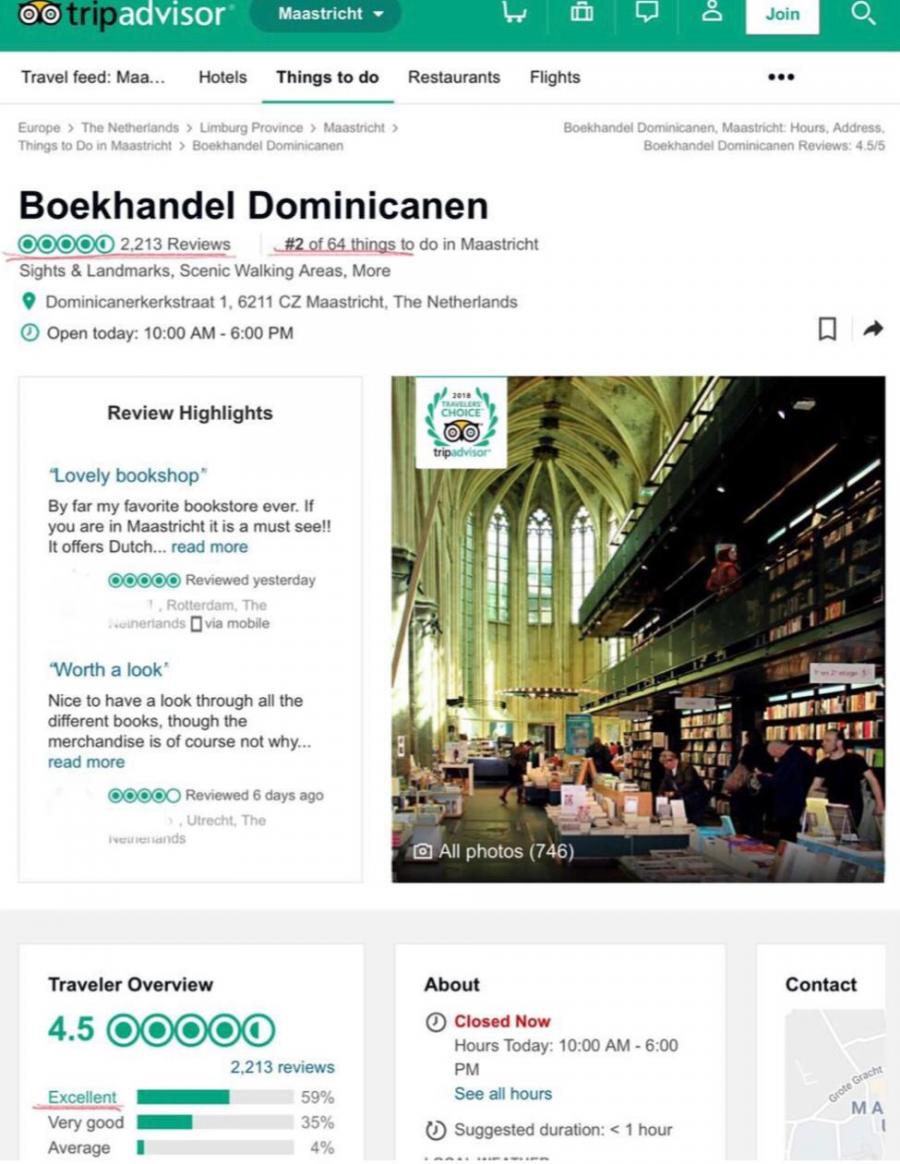

Figure 5: Boekhandel Dominicanen in Maastricht.

In Maastricht, the Boekhandel Dominicanen (Figures 5 and 6) is a famous landmark which scores second place of must-visit locations on TripAdvisor (Figure 7). The old church was turned into a bookshop and attracts thousands of visitors every year. The inner design has been slightly modified, however elements typical of a Catholic church, such as the cross, have kept their central place in the design. As we can see in the picture above, the cross-shaped reading table stands in the middle of the church.

Figure 6: Boekhandel Dominicanen in Maastricht.

Figure 7: Boekhandel Dominicanen on TripAdvisor.

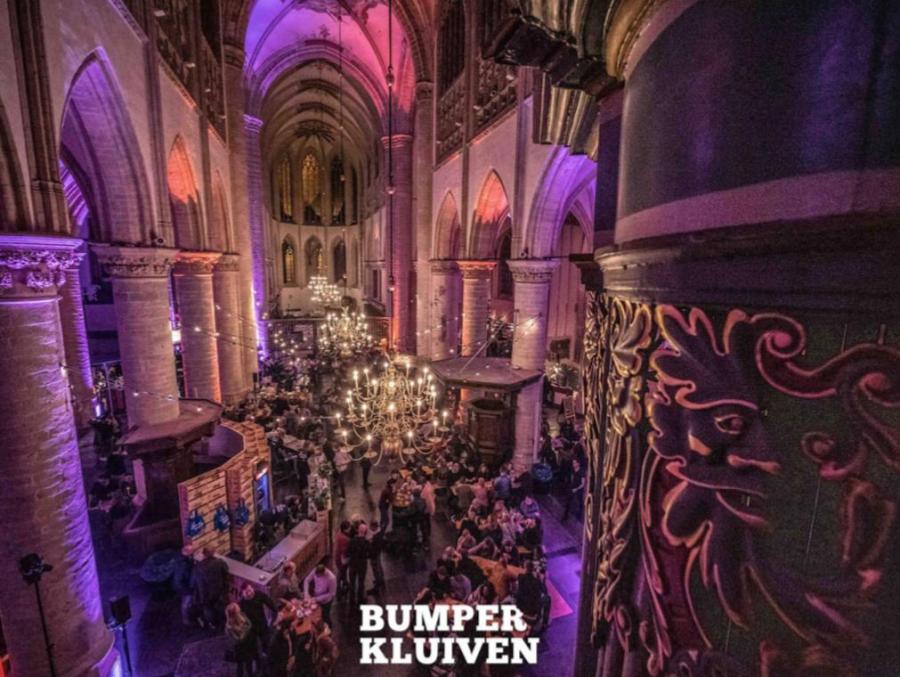

In Breda, food festivals in ‘de Grote Kerk’ (Figures 8 and 9) take place regularly. On the Facebook page of the most recent event, 185 users pressed “going” and 798 “interested” (17.12.2018), which makes one thousand people who showed their digital activity concerning this event. The photos from the festival also show the high attendance of the church on the day of the food festival.

Figure 8: Food festival in ‘de Grote Kerk’, Breda.

Figure 9: Food festival in the church in Breda.

In Gouda, temporary ice skating rink was set up in the Gouwekerk in 2018 (Figure 10). The event was particularly popular among local children.

Figure 10: Ice skating rink in Gouwe Kerk, Gauda, the Netherlands.

In 's-Hertogenbosch, the former monastery Mariënburg is now used as a part of Jheronimus Academy of Data Science (JADS). The location became the main campus of the academy and "offers modern education facilities, as well as space for startups and partners. Above all the campus has been designed as a place where interaction, networking, training, master classes and the exchange of skills and know-how take place and feed the data science community" (JADS, 2019).

Figure 11: Jheronimus Academy of Data Science (JADS) in 's-Hertogenbosch.

Societal debate

The notion of reuse or recasting church buildings has led to broad discussions in society. First of all, many do not understand any other use of churches except the traditional one. This, in many cases, depends on individual religious involvement.

Some justify the new use of churches by connecting it to the dense population of the country and thus making use of all the places that allow for social gathering (The New York Times, 1997). Others connect the number of new projects involving churches with the growing commercialization of society. “The growing number of superfluous churches is central at this time, with interest strongly geared to policy with finances looming in the background and often in the foreground. The whole question of superfluous churches, the heavy cost of maintenance of monumental churches and all kinds of difficult plans for reuse and new uses lead to various policy memos” (Post, 2014).

The new uses of sacred spaces are in the sphere of interest of policymakers and local authorities. The reorganization is profitable because the renewed church spaces usually attract a sufficient amount of media attention and thus guests who generate money flow.

Many visitors attend such renewed places because of the spectacle element, where the church plays a role of a ‘forbidden place’ which has never been seen and used as a place to relax and have fun in. This attitude sometimes faces criticism due to traditions anchored in society. “Various forms of alternate uses [of churches]... raise all kinds of questions” (Post, 2014). There is a thin line to this debate, however, young people tend not to perceive reuse as a problem.

Churches as spaces for social gatherings

The reuse of church buildings is not only a sign of a changing attitude towards religion, but also a way of cherishing the building as such. The building keeps its special place in a community, not for its religious purposes but for the symbolic meaning it has for the community. It is, in a certain sense, an identity marker both in the landscape and in the life of the community. Although not many go to church, there is an ‘us’ who claims the building. The once religious-ritual place maintains its function as a sacred place, a place for musical rituals (concerts), wisdom (in books) and sharing food. A new play between the sacred and the profane takes place. For Durkheim, “religion involved the classification of phenomena into the sacred and profane, that is, things that are set aside and forbidden” (Turner, 2011). It can be said that with contemporary church projects, the two are overlapped and mixed.

“In the Christian tradition, the church building is constantly associated with the possibly universal tradition of ritual place as a special place that is set apart” (Post, 2014). The building of the church is traditionally perceived sacred, “set apart and forbidden” (Turner, 2011), the place of strict order and spirituality. This “...basic sacrality of place is constantly a topic of discussion from the Christian perspective” (Post 2014, Turner, 1979). At the same time, as a location for food festivals, concerts or dance events, it involves a profane “part of the everyday world” (Turner, 2011) activity. This stands exactly in line with the decline of religious participation, where people are not motivated to go to church for traditional religious activities anymore, but still prefer to keep them as places for social gatherings. Churches have always served as ‘totems’ for communities (Durkheim, 1912), and functioned as ‘social glue’.

One of the reasons why events in church buildings are so popular is, of course, the element of spectacle. Churches look beautiful, have architectural value and open up from new angles for those who visit them. The sacred atmosphere combined with new decorations give the visitors an experience of being part of ‘something’ that transcends the self. The visitors feel unified due to the experience of the place.

Due to the contemporary reuse of church buildings, the social function of these buildings will be maintained. The mixture of the church building as a sacred place and more or less profane activities within the walls of these buildings leads to new communities. Churches still function as ‘social glue’, bringing people together even in times of religious decline.

Religion and churches now

“Religion survives because it satisfies a basic social function, not a psychological one. Thus Durkheim argued that ‘No society can exist that does not feel the need at regular intervals to sustain and reaffirm the collective feelings and ideas that constitute its unity and its personality’" (Turner, 2011). Through reuse church buildings maintain their function as centers for social gatherings and cohesion. This is religion in a Durkheimian sense: religion is not a set of doctrines, but of practices: singing, reading, dancing in amazing beautiful places like a church building.

References

Berger, P. L., Davie G., Fokas E. (2008). Religious America, Secular Europe?: A Theme and Variation. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

De Hart, J. (2014). Believe inside and outside connection. SCP.

Durkheim, E. (1912). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life.

European Value Studies. (2018). Religion: Church attendance – Confidence in the church – Importance of God – Traditional beliefs.

JADS, (2019). Campus Mariënburg.

Norris, P., Inglehart R. (2011). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

Pieters, J. (2018). Catholic church rapidly disappearing from Netherlands,

Archbishop says. NLTimes.nl.

Post, P. (2014). Complexity and conflict. The contemporary European church building as ambiguous sacred space, in Paul Post, Philip Nel & Walter van Beek (eds.): Sacred spaces and contested identities. Space and ritual dynamics in Europe and Africa. Trenton: Africa World Press, 241-265.

Simons, M. (1997). Neglected Churches Are Given New Use In the Netherlands. The New York Times.

Turner, B. S. (2011). Religion and Modern Society: Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge University Press.

Turner, H. W. (1979). From Temple to Meeting House: the phenomenology and theology of Places of Worship. New York: De Gruyter Mouton.