Pan-Slavism, Russian populism and the annexation of Crimea

The historical events of 2014 in the territory of Crimea, Ukraine, had a broad significance for European history. They have brought war closer to the borders of the European Union and put more tension on the region. The annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation happened in February/March 2014. The event raised questions regarding NATO’s position against Russia and how NATO might not be so effective in defending Europe.

Apart from these considerations, the issue sparked a discussion on Russian nationalism and Crimean regionalism, as well as Ukrainian identity. The divisions between the multicultural population of the peninsula and the lack of promotion of Ukrainian identity played a role in the annexation process. This article will discuss the historical background of the events, the process of annexation, social media response to it, and the present-day situation in Crimea regarding populism.

Our hypothesis is that factors that played a role in the referendum of 2014 in Crimea and in the annexation process were partly shaped by the ideological ideas of Pan-Slavism. The rhetoric used in this movement is strongly reflected in Russian populism in Crimea. This has been the case also in the years preceding the event. The rhetoric of Pan-Slavism and its application in the case of Crimea is also strongly in line with the very essence of nationalist and regionalist ideas in the region. The question we will try to answer thus pertains to how Pan-Slavism and populism contributed to the annexation of Crimea in the context of regionalism and Russian nationalism.

Figure 1: The Crimean peninsula on the map of Central and Eastern Europe.

To answer this question, we are going to use digital ethnography. This study deals with numerous posts and online data from Runet. Among the platforms we looked at were Vk, Ok, Yandex, YouTube, Facebook, and other widely used platforms. We also delved into additional literature, local and international media, the chronology of the events of 2013-2014 in Ukraine, as well as the broader context and rhetorics of the region in the years before the annexation.

In order to understand the situation in Crimea it is important to understand nationalism and regionalism. Anderson (2006) defines the nation as an “imagined community” which constitutes the core of nationalism: a strong feeling that our nation is superior to other nation states. Regionalism, on the other hand, is a form of “minority nationalism” in which the region’s nationalism is in opposition with the nation state (Lecours & Nootens, 2011). In the case of Crimea, regionalism was very much present in the region. The media portrayed Crimea as not wanting independence and as accepting of the annexation by Russia, which shows that they focused on a rhetoric about strong nationalistic feelings towards the former motherland. Thus, nationalism in Crimea is strongly related to Russian nationality and Crimean regionalism is in opposition to the Ukrainian nation state.

The historical preconditions of Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism is a political ideology that has spread in Eastern Europe. Most commonly, Pan-Slavism refers to the idea of all slavic-speaking peoples (see Figure 1) being united in one country against their internal and external enemies. It is a “vague, semi-poetic, semi-philosophical idea of a great Slav race with a common life in the remote past and with a great common destiny in the more or less misty future” (Levine, 1914).

Figure 2: Slavic-speaking countries on the map of Europe.

The first signs of Pan-Slavism developed in the middle of the 16th century and the ideology “is branded in our days as the real cause of the conflagration now ravaging the fields of Europe” (Levine, 1914). This timeframe was not accidental, as it is connected to the development of interest in Slavic folklore, history, and languages. Some scholars, however, trace Pan-Slavism to the “fall of the Eastern Empire in the fifteenth century” (Levine, 1914).

The ideology strongly reflects the negative angle from which most Slavic countries perceive their historical past. Due to the political context and their geographical position, many countries have been experiencing years of ongoing wars between what is now commonly referred to as "Western Europe" and the Russian and Ottoman Empires. “To German, Magyar, and even Turk, the Slav seemed an inferior being who had achieved nothing in politics or in the arts of life. The reaction against this was a desire on the part of the Slavs to assert the value, not of this or that particular Slav people, but of the whole Slav race as a whole” (Levine, 1914). In a nutshell, to create a national spirit, various great achievements and great minds from separate Slavic countries are glorified, including political leaders of Russia, Ukrainian poets, Serbian artists Polish scientists, and so on. They are then interpreted as “illustrations of the common genius of the race. This naturally led to emphasis on the common origin of the Slavs and their bonds of kinship” (Levine, 1914).

In the contemporary context, internal enemies are considered to be refugees and migrants. This is due to the fact that after the fall of the Soviet Union, migration from former communist countries to Russia started rising. According to research by the United Nations (2017), around the year 2000, the Russian Federation became the second country with the highest influx of international migrants. This fact has sparked nationalist movements in Russian society, as well as nation-oriented rhetoric (Vdovychenko, 2019). Since Russian media are widely broadcasted in the Eastern European region, this partly explains the feeling of common identity nurtured there and the experiencing of common problems. However, it cannot be claimed that this was the sole reason for the development of right-wing populist rhetorics in the whole region. Every country and every case is unique. The Russian Federation shows us one of the prominent examples of why Pan-Slavism is flourishing in the public sphere nowadays and why is it still one of the pillars of the country's nationalism.

External enemies, from the Pan-Slavic view, are "the West" and recently, with the growing economic strength of the People's Republic of China, the Global East. These external actors are usually talked about as ideological and physical threats. By outlining the cultural and political enemies of Slavic-speaking countries, what is being emphasized is the difference between "us", the Slavs, and "them" - all those who work against the Slavs.

Pan-Slavism, although not talked about explicitly in the public sphere, has a huge influence on Eastern European politics. “It was said to be at the root of Balkan disturbances during the early part of the nineteenth century” (Levine, 1914), and since then, it is argued to have actively interfered with the political climate of Europe. What is particularly applicable to the recent conflicts on European soil is that even “The government of Russia is supposed to have been consciously inspired all these years by the vision of a great state in which all the Slavic peoples would be nestled under the wide wings of double eagles” (Levine, 1914).

Pan-Slavism in the contemporary context is based on a few key criteria. These are being promoted in both the public sphere more broadly and online environments specifically. Among them we could differentiate three aspects:

- a common historical past,

- religious ties,

- territories and language.

References to common historical past, religious ties, and especially territories and language, influenced the self-identification of Crimean citizens in the years before the annexation of the peninsula. It was a strong marker in the determination of their national identity and it played a role during the deciding referendum of 2014. Let us review these key aspects.

Common historical past

The glorification of historical past plays a huge role in the construction of Pan-Slavism. Ever since the emergence of the ideology “The Slavic peoples had first of all to prove their claim to nationality. There was nothing in their present which seemed to justify it. So they turned to the past, where each Slavic people hoped to discover memories of glory and traces of national greatness” (Levine, 1914).

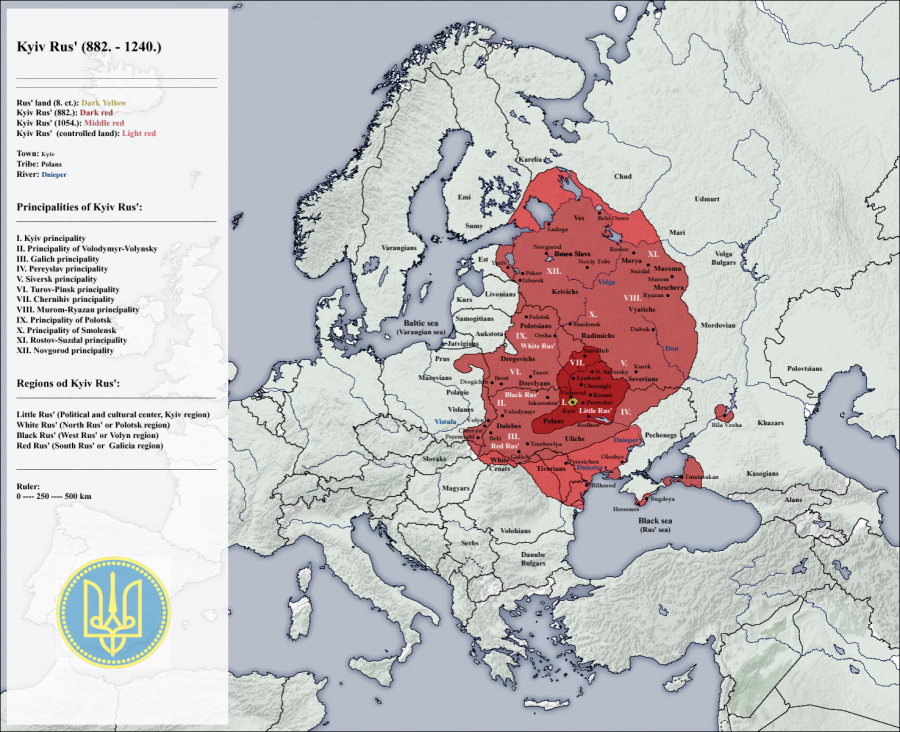

Figure 3: The map of Kyivan Rus..

The rhetoric of contemporary Pan-Slavism, according to thematic social media groups on Vk, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (Vdovychenko, 2019), references historical past as one of its main pillars. In general, Pan-Slavism massively contributes to the political ideology of such countries as Russia, Belarus, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Serbia, and others (Vdovychenko, 2019). It consists in an overarching feeling of identity and common Slavic nationalism.

According to Shils (1995), “Nations exist because of the sensitivity of human beings to the primordial facts of descent and territorial location” (Shils, 1995). In Pan-Slavism the idea of a territory inhabited by Slavic populations throughout centuries of European history is one of the Slavs' main bonds. These countries position themselves as belonging to the larger frame of common history, emphasizing a common past, for example Kyivan Rus (seen in Figure 3), a medieval federation of slavic tribes which is believed to be the original birthplace of Slavic people, and the Soviet Union.

Both factors are quite significant as they capture the unity and imagined power of Slavic peoples. Such a rhetoric awakes a nostalgia for the "glorious past" amongst these populations, and promotes the idea of a common future by emphasizing modern-day "enemies".

Religious ties

Religion is of major importance in the context of Pan-Slavism. It has an ideological purpose as it helps shape the ideal image of the behavior of every Slavic individual. The overarching religious view of Pan-Slavism could be divided in two branches: Slavic Paganism and Christianity.

Slavic Paganism, sometimes also referred to as "Slavic Native Faith" serves as a marker of a more ancient identity of Slavic peoples. It creates a virtual (or imagined) bond between different countries, and shows their significance in the past in the sense that they were present and strong even before the Christian times.

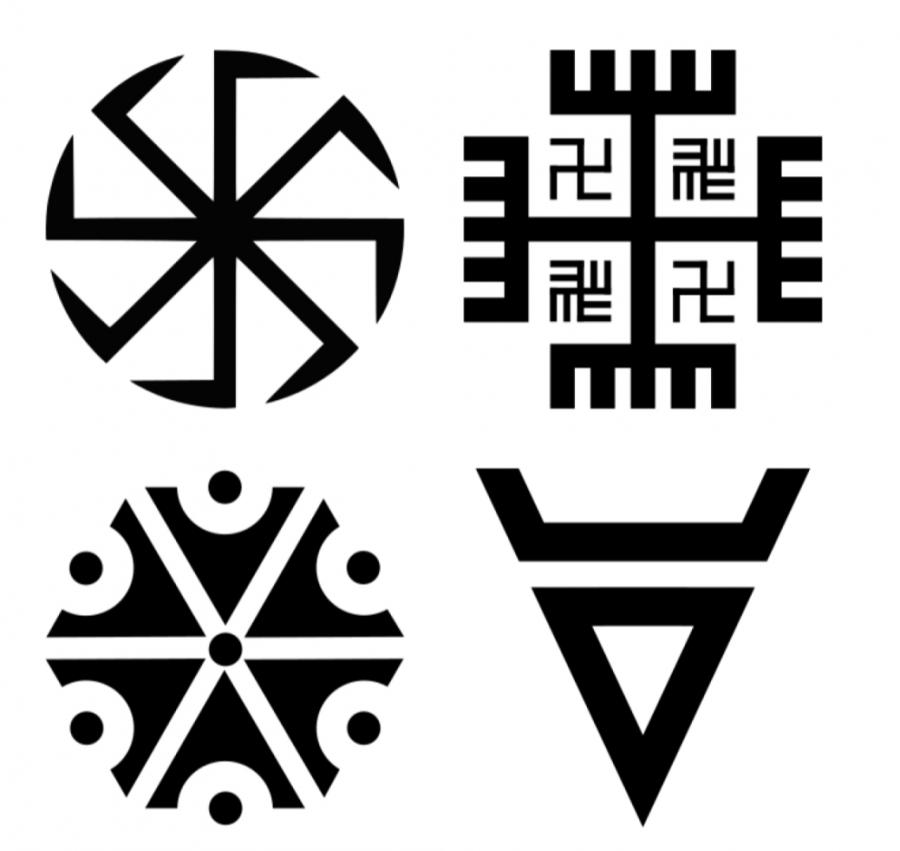

Figure 4a: Examples of swastikas and related symbols used by pagan Slavic tribes.

In radical right movements, Slavic Paganism serves as a justification for using runes, swastikas, and other related symbols, sometimes also interpreted as related to nazism or the far-right in contemporary contexts. Radical groups justify their usage as a reference to their ancient pagan religion. In Slavic Paganism these symbols played a role and were commonly interpreted as symbolizing happiness, sun, light (Telepina, 2012), and eternal life (see Figure 4a).

Figure 4b: Distribution of Christian Orthodoxy in Europe.

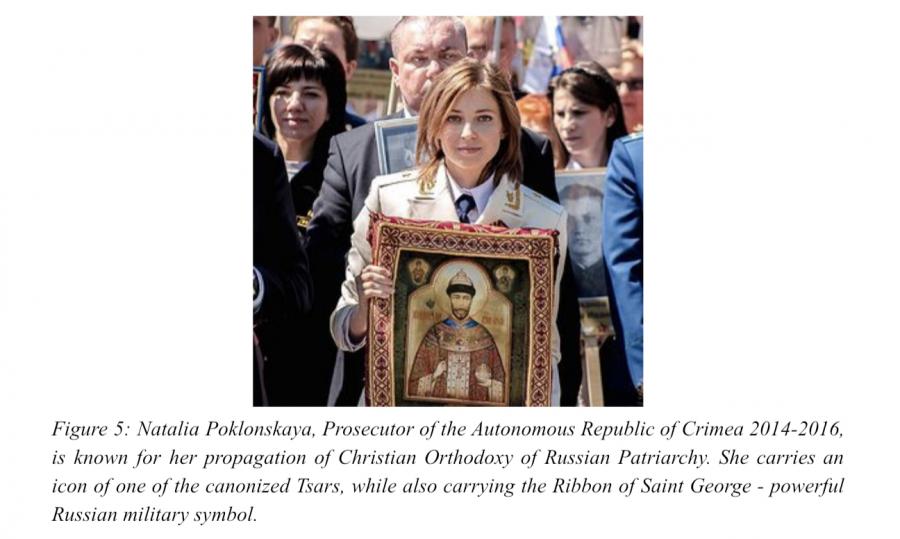

The religious bond most often emphasized, however, is that of Christianity. The two dominant streams of Christianity in Slavic-speaking countries are Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Even though the focus varies greatly depending on the country, the predominant religion in the Pan-Slavic rhetoric remains Orthodox Christianity (Vdovychenko, 2019). This could be linked to its prominence in the Russian Federation, where Orthodox Christianity has a very powerful influence with 42,5% of Russians identifying as Orthodox Christians in 2012 (Arena, 2012). However, a number of Eastern European countries also have Orthodox Christianity as their predominant religion (see Figure 5) and the creed thushas a powerful influence in the region. In the case of Pan-Slavic ideology, it contributes to the image of "us", Orthodox Christians, against "them", Catholics, Protestants, and people of Muslim or Jewish backgrounds.

Territory and language

Pan-Slavism enthusiasts proclaim that the territory of all Slavic-speaking countries, if merged together, would make it the biggest Union and the strongest political power in the world. It would also be a massively populated territory with numbers of expected inhabitants varying between 280 to 300 million (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Visualization of how a Pan-Slavic country would ideally look like, made by YouTube channel Slavic Affairs.

Historians and researchers responsible for the creation of Pan-Slavism emphasized the need for Slavs to have a new language that would include words and grammatical structures understandable by all Slavic people. However, in practice, the language most commonly referred to in Slavic nationalist rhetoric is Russian. This is also due to the Russification policy of the USSR and the glorification of the Soviet Union in Pan Slavic rhetoric. The Russian Federation is also the largest country of the world, which nicely coincides with Pan-Slavic ideas. This has also played a significant role in the case of Crimea.

The Crimean crisis: Historical background

Crimea has a long history which, with the rise of the Soviet Union, became a rather controversial topic. Its recorded history starts in the 5th century BC. The peninsula has also been a part of Kyivan Rus - the predecessor of contemporary Ukraine and the Crimean Khanate - as well as of the Ottoman Empire.

Since then, in 1783, the Crimea was first annexed by the Russian Empire, and then became first a part of the Russian SFSR, then a part of the Ukrainian SSR (BBC, 2018). Its transition from being part of Russia to being part of Ukraine raised much discussion and was featured in political propaganda in the years before the annexation. The transition has been called a "symbolic gesture" by former leader of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev, dedicated to the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s joining the Tsardom of Russia (Krishnadev, 2014). While the event is controversial because Ukrainians have been fighting against Russian rule for years, the Ukrainian side often specifies that before the transition the Ukrainian SSR gave away its territories, excluding the territory of Crimea (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Ukrainian ethnic population of Russia, according to the European part of the RSFSR under the census of 1926 (Atlas of Ukrainians, Eastern Diaspora - K., MAPA, 1993).

In modern times, however, the Crimean peninsula region remained quite problem-ridden. Due to the Soviet internationalisation policies of the past, the territory is considered to be home to three different nationalities: Ukrainians, Russians, and Crimean Tatars. Every one of them, naturally, has its own customs, religion, language, and claims to ownership of Crimean territory. While the Ukrainian government did not oppress the minorities and allowed them free media, expression, and languages, it later played a significant role in the annexation process.

In 2013, President Viktor Yanukovych of the Party of Regions suspended the signing of the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement, which sparked protests in Ukraine. A revolution followed that ousted Yanukovych, which sparked a political crisis in the Crimean peninsula. Yanukovych was strongly supported by the Crimean region and Eastern Ukraine. The Crimean government called for a formation of a “people’s militia”, and on the night of 22-23 February, Russian President Vladimir Putin had an all-night meeting with security service chiefs to discuss the extrication of the deposed Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych. At the end of that meeting, Putin remarked that "we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia” thus starting the process of Crimea getting closer to the Russian Federation, the country that would listen to the will of the Crimean people.

Language as a dominant part of Crimean identity politics

Language is often seen as one of the most predominant attributes of a specific cultural or national group. Through language, people socialize and make meaning of their lives. “Language use is a form of self-representation, which implicates social identities, the value attached to particular written and spoken texts, and therefore the links between discourse and power between in any social context” (Pavlenko, 2006). The tensions between Russian and Ukrainian in Ukraine influence power relations in the country. The identity of Crimean Russians is signified by their usage of the Russian language.

One of the main factors that contributed to the annexation of Crimea by Russia is the argument brought forward by politicians that the majority of Crimean inhabitants speak Russian anyway. It is important to note that 65% of the population in Crimea identifies as Russian, thus the populist approach of “listening to the voice of the people” played a role in establishing the Russian identity of Crimea. Listening to the Russian majority's claim that Crimea belongs to Russia led to the annexation.

Due to the majority of Russian speakers in the Crimea, Russian media propagated the idea that the language is a main signifier of "Russian identity", and the will of the people was therefore to join Russia, the motherland. As we have discussed above, Crimea was already part of the Russian Empire in the past, and its common history with Russia also played a role in triggering a “nostalgic” longing for the glorious past, in which Crimea was part of an Empire.

Moving back to the linguistic landscape in Crimea, the Russian language is not only dividing the people of Crimea, but it also plays a huge role in the entire country. The ongoing conflict between Ukrainian Orthodox churches where Ukrainian is spoken and Russian Orthodox churches divides people into two camps. The ongoing conflict between Ukrainian Orthodox churches where Ukrainian is spoken and Russian Orthodox churches remains controversial. However, Russian is used as a day-to-day communication tool in the entire country, especially in the capital, Kyiv.

.Although Russian is in active use in some of the country's regions, "[...] no Ukrainian would interpret this as an expression of geopolitical sympathies” (Dickinson, 2018). Yet, in the case of Crimea the propaganda really worked even though speaking Russian is common accross the country.

Russian populism in Crimea

According to Mudde (2004), populism is “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” Populism claims to represent the voice of the people, but it never makes clear who these people are.

In the case of Crimea, populism was present in the form of "we, the Russians" who should protect the integrity of the Russian language against the Ukrainian state's intent to abolish regional languages and maintain the sole usage of Ukrainian. “Peripheral communities often urged the state to play a more active role in their region by invoking their national identity” (Storm, 2003). In the Crimean case, Crimeans waited for support from Russia, identifying with the Russian national identity. Thus, Russia was regarded as the only state that could solve the problem. In the referendum of Crimea (not recognized by many countries), it turned out that 96% of the people who participated voted to join the Russian Federation.

Figure 8: Post circulating online of Vladimir Putin in Soviet style propaganda. The post says "Crimea is ours. Trump is ours. Whose are you?"

Populist discourse in Crimea revolved around the same rhetoric we hear from the president of the United States, for example. The people of Crimea want to join Russia (as claimed by Natalya Poklonskaya) and the politicians need to listen to the voice of the people. In this populist approach, it was Crimea that decided to join Russia and not Russia that annexed this territory. In this way, it was easier to annex the territory because things were made to look as if the people really wanted this. The subsequent referendum victory only strengthened the populist representation of Crimea’s will.

Crimea: a win for Pan-Slavism in Russia

For the Russian Federation, annexing Crimea felt like a huge success both because of its rich resources (according to NATO, n.d., “It has vast offshore oil and gas resources in the Black Sea, estimated between 4-13 trillion cm of natural gas”), and because of its expansion in terms of territory. Returning to the idea of Pan-Slavism, which refers to the glory of Slavs, Russian Pan-Slavism is a related ideology that represents a right-wing, populist and nationalist version of Pan-Slavism that praises Russia’s glorious history. It is the Russians' own adaptation of nationalism that views Russians as the superior Slavs, who have a glorious past. According to MacMillan (2010),“History provides much of the fuel for nationalism. It creates the collective memories that help to bring the nation into being. The shared celebration of the nation’s great achievements sustain and foster it”. Bringing Crimea, a region that used to belong to the Russian Empire, back into the country’s borders meant that the country was finally starting to expand and to "regain its former glory".

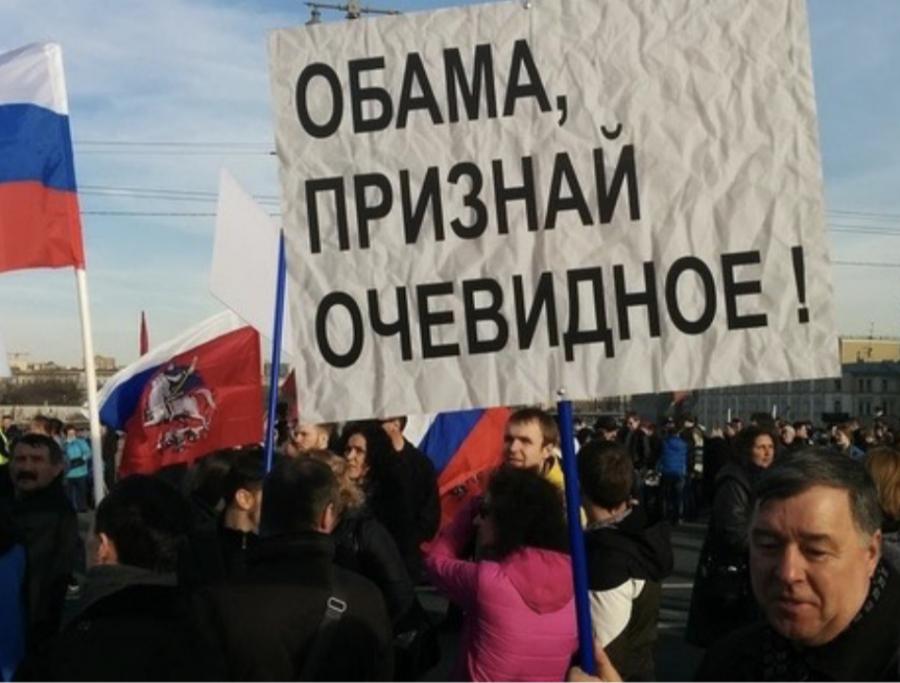

Figure 9: The poster "Obama, acknowledge the obvious!" at the meeting in Moscow dedicated to the 1-year anniversary of the annexation of Crimea.

Pan Slavism is now associated more with Russian expansionism. It can be seen online, on the VK platform, and similar platforms of Runet, such as Ok.ru, Yandex, and others. The annexation of Crimea has become an important part of Russian Pan-Slavic-centered propaganda. It is also associated with the successes of the current president, Vladimir Putin (see Figure 8). Pan-Slavists from Russia were praising the fact that Crimea was finally annexed. The annexation rhetoric is perceived as a win against "the West", and more precisely the US (see Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 10: “Crimea is ours”, online sticker circulating on Runet with a map of Crimea in the Russian flag's colors and with a balalaika, a musical instrument symbolizing Russia.

The online usage of such memes by contemporary Pan-Slavists in Russia emphasizes the role that social media play in maintaining this ideology. The memes and screenshots featured in this article are just a few examples of Russian propaganda regarding the Crimean “victory”. The online rhetoric of Pan-Slavists revolves around the ideas that this is just the beginning, and that Russia defeated NATO and the West in general. Because of the dichotomy between "the West" and Russians, we can conclude that this is a typical populist approach that puts Russians in a ideological conflict with the West.

Pan-Slavism on social media

When talking about populism, “the affordances and the algorithmic nature of web 2.0 should be taken on board” (Maly, 2018). Algorithmic populism is a new and progressive dimension which “refers to a new manifestation and form of populism in the digital age” (Diggit, 2018). We have researched some of the relevant online groups in order to find evidence of online populism and propaganda for Pan-Slavism.

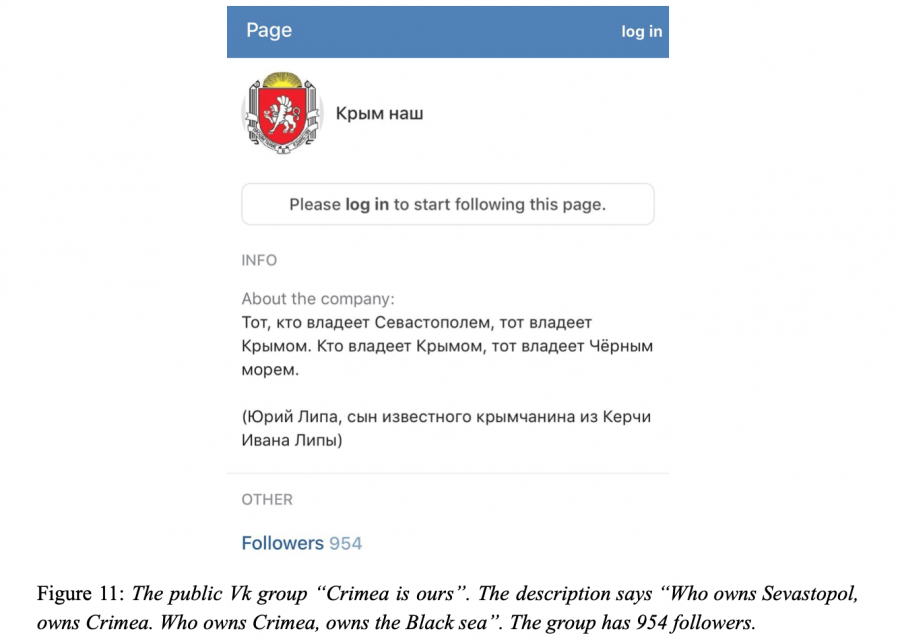

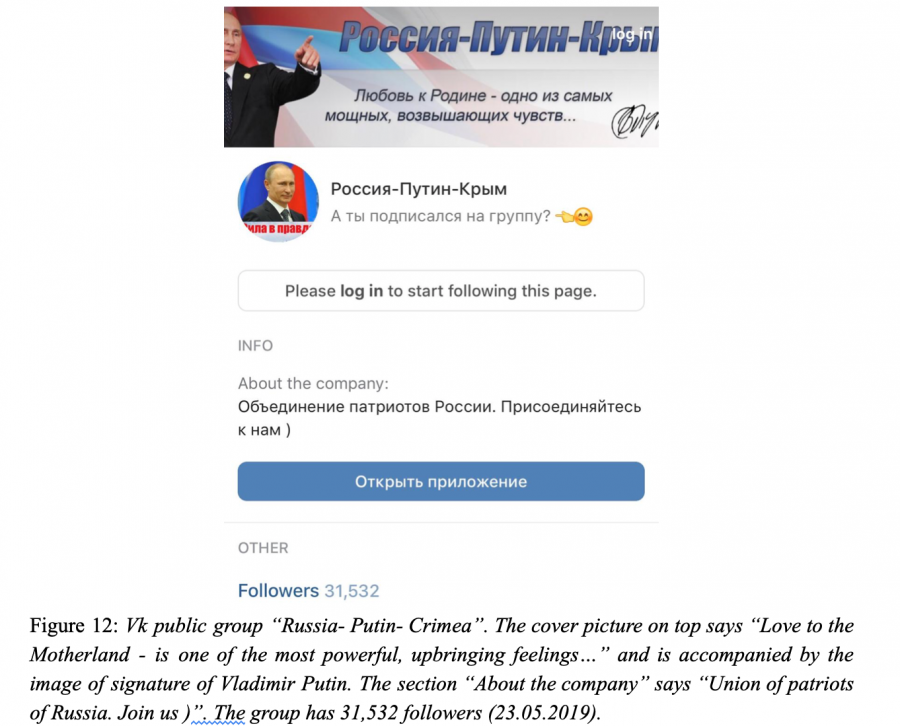

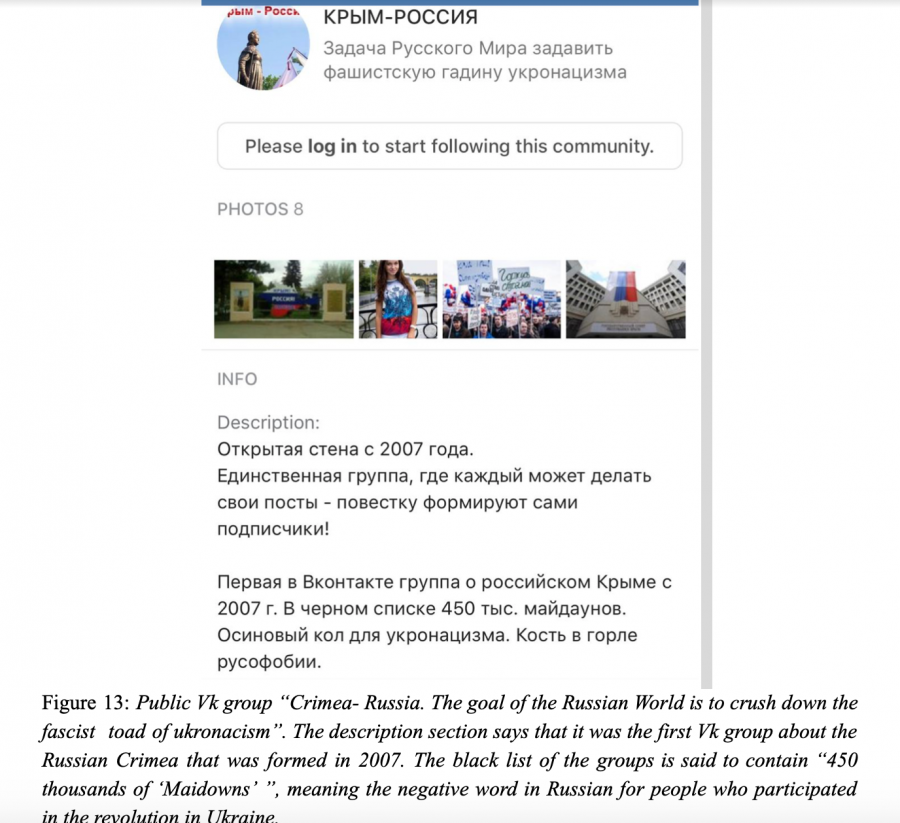

The platform Vk (the so-called "Russian Facebook") is the most widely used platform of Runet and one of the most effective instruments in spreading Pan-Slavic propaganda. In the Crimean case, we managed to find a number of public groups that would glorify Crimea as a part of Russian Federation. They all use the slogan “Crimea is ours” - a typical phrase signifying the glory of the reconnection with the peninsula (see Figure 11). In such public groups one can see the nationalist feeling attached to the annexation of the Crimea. Figures 11, 12, and 13 all glorify Russia in terms of a broader perspective of being a glorious nation with one powerful leader. Some of the messages, such as those presented in Figure 13, are quite radical. All of the groups have quite a broad scope of followers.

Within the groups, the content is diverse. Users post news, memes, informative content. However, the thing all of them have in common is the glorification of the great nation and its leader. Below, we present examples of how the Pan-Slavist message of the unification of Slavic peoples and the power of Putin's Russia are being broadcasted on social media. For example, Figures 14, 15, and 16 present Putin in images signaling"coolness", lionizing his role in the annexation of the Crimea. Through the use of memes, Pan-Slavist ideology and Russian populism reach younger generations who use social media as a main source for news and information. At the same time, Putin is popularized among the youth.

Figure 14: “Got Crimea back”.

Figure 15: “[Dmitry Medvedev] Dimka, [drinking] to you!!! Crimea is ours!”

Figure 16: “This guy was from those who simply just love Crimea”.

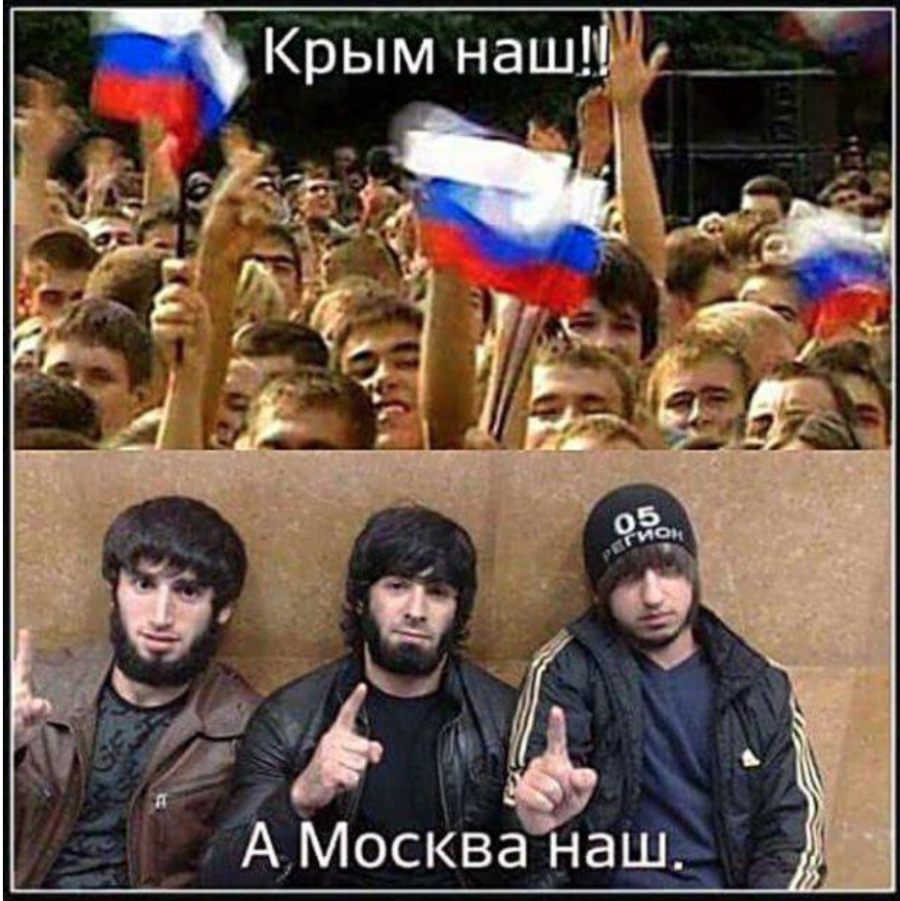

However, Putin is not the only figure promoted on social media. Vk public groups with a focus on the Crimea, the Slavic world, Russian populism, and related topics contain a lot of entertaining content in line with Pan-Slavic ideology more generally. They show the power of the nation and the beauty of truly Slavic people (Figure 17) or they highlight the expansion of the possible Union and of the Russian Federation (Figure 18). The pictures, sometimes explicitly and sometimes in a less conspicuous way, also invoke the historical context (Figure 19) or warn against the West/East or the influx of migrants (Figure 20). In this way, through seemingly unremarkable pictures online, deep and powerful messaging is being spread through social media.

Figure 17: Stylized Natalya Poklonskaya demonstrating power with a weapon. The writing reads “Crimea is ours” and in the background the map of Crimea is displayed with the Russian flag and symbol.

Figure 19: "Before" and "after", showing the "expansion of the great nation".

Pan-Slavism as a tool of Russian nationalism?

Russian nationalism together with Russian Pan-Slavism have contributed to the annexation of Crimea, as they eased the Russian-speaking population in the Crimea into voting to join the Russian Federation. Since the Russian-speaking population in Crimea was the majority, the annexation happened. The role of Russia and its president Vladimir Putin was presented as protecting the will of the people living in Crimea. In this way, populist discourse made Crimeans feel as if they would have a better life in Russia, a country regarded as the most likely to respect the will of the Crimeans. As nationalism in the Crimean region was strongly Russia-oriented, its regionalism was in opposition to the policies of the Ukrainian state. Crimea never asked for independence because they simply wanted to belong to Russia, as they agree more with Russian political ideals than Ukrainian ones, which are more aligned with the West.

Figure 19: “When you got to know that Crimea is ours again.”

Figure 20: Glorifying the Slavic (Russian) nation, while warning of migrants. “Crimea is ours, [...] Moscow is ours”.

Thanks to social media, the annexation of Crimea was the central topic of Pan-Slavist memes. From idealizing Putin to promoting strong Russian expansionism ideals, social media were effectively used by Pan-Slavists in Russia to distribute their political propaganda.

Most of the aspects covered when discussing Russian Pan-Slavism are also applicable to Crimea: both Crimean and Russian Pan-Slavists identify with the glorious historical past of the Russian Empire and both of them express a strong support for Russian Orthodoxy, in spite of the fact that in Crimea there is a community of Muslim tatars. Natalia Poklonskaya served as the main mobilizer in forging a populist discourse that stressed Russian identity, whereby she emphasized the connecting features of language and religion. We can thus see how the extreme nationalism of Pan-Slavism and a populist approach contributed to the annexation of Crimea.

References

Anderson, B., (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities. (2012). Атлас Религий и Национальностей. Российская Федерация. Среда.

BBC. (2018). Crimea profile.

Dickinson, P. (2018). They Speak Russian in Crimea, but That Doesn't Make It Part of Russia.

Diggit, (2018). Algorithmic populism. Diggit Magazine Wiki.

Krishnadev, C. (2014). Crimea: A Gift To Ukraine Becomes A Political Flash Point. NPR.

Lecours, A., Nootens, G. (2011). Understanding Majority Nationalism’ in: Contemporary Majority Nationalism. Studies in Nationalism and Etnic Conflict. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Levine, L. (1914). Pan-Slavism and European Politics. Political Science Quarterly, 29(4), 664-686.

MacMillan, M. (2010). The uses and abuses of history. Profile.

Maly, I. (2018). Populism as a mediatized communicative relation: The birth of algorithmic populism. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 213.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government & Opposition, 39(3).

Nato. (n.d.). The energy dimensions of Russia's annexation of Crimea.

Pavlenko, A. (2006). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Storm, E. (2003). Regionalism in History, 1890-1945: The Cultural Approach. European History Quarterly Volume, 33(2).

Shils, E. (1995). Nation, nationality, nationalism and civil society. Nations and Nationalism, 1, 93-118.

Telepina, J. (2012). СИМВОЛ В РОССИЙСКОЙ КУЛЬТУРЕ. Тамбов: Грамота.

United Nations. (2017). International Migration Report 2017 [highlights]. Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Vdovychenko, N. (2019). Slavic Union is on the rise in Eastern Europe. Diggit Magazine.