War from the rabbit hole: the media literacies landscape of TikTok during the Ukraine conflict

With TikTok currently being one of the main centers of global communication, its new affordances invite new media literacy practices. In this article, we provide an empirical overview of how TikTok implements top-down media literacy policy and how users develop bottom-up media literacy practices in reaction to the information disorder surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine. And we theorize how these efforts might actually be counterproductive.

After months of rising tensions, Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022. It signified an intense escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict that has been underway since 2014. A year after the initial invasion, the Ukrainian war has become marked by physical dirt, death and destruction. But in addition to physical battles on the ground in Ukraine, the Russian invasion in early 2022 incited an information war that reached far beyond the Ukrainian borders. Framing efforts, propaganda and disinformation from both sides of the conflict were spread across the globe through digital media (News Literacy Project, 2022). To speak with Claire Wardle, ‘information disorder’ played a significant part in the early fases of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Information disorder and media literacies

Claire Wardle introduced the concept of ‘information disorder’ in 2017 in reaction to the popular term ‘fake news’. She writes: “Most of this content isn’t even fake; it’s often genuine, used out of context and weaponized [...]. And most of this can’t be described as ‘news’. It’s good old-fashioned rumors, it’s memes, it’s manipulated videos and hyper-targeted ‘dark ads’ and old photos re-shared as new.” (Wardle, 2019). The concept of information disorder comprises all these forms of (possibly) misleading information.

In the past years, media literacy skills have been presented as solutions to the proliferation of information disorder. And even though the efficacy of media literacy practices in the ‘fight’ against information disorder has also been questioned (e.g. Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017 and Jones-Jang et al., 2021), we now see TikTok (2022) continuing this tradition of promoting media literacies in reaction to the information disorder on their platform surrounding the 2022 Ukraine conflict. Following Johnson’s (2013) study of literacy policy, these media literacies could be developed in a top-down, macro-level, overt, explicit and de jure manner, and in a bottom-up, micro-level, covert, implicit de facto manner.

Information disorder has always been around, especially during wartime

In what follows, we analyze both these top-down media literacy policies and the bottom-up media literacy practices developed by TikTok users. In our analysis, we take into account the historicity of information disorder during conflict, and how TikTok’s affordances reflect and shape this new era of mis- and disinformation. For these purposes, we initiate our analysis with a historical view on two past conflicts that both represent turning points in the role of media during conflict: the Gulf War of 1991 and the Arab Spring of 2010.

The Gulf War and the CNN effect (1991)

The 1991 Gulf War is often seen as a tipping point in media coverage of conflicts. One important player in this event was the American news channel CNN, which was one of the very few Western media outlets that was able to broadcast the war live to hundreds of millions of people worldwide from the very beginning. This is considered the first time war was covered live on television for everyone around the world to see and it changed the media landscape (Johnson, 2017).

People did not see the “real” war, but a “told” and “imagined” war

According to media philosopher Jean Baudrillard, the way the conflict was portrayed highly impacted the way it was perceived (Van Doorn et al., 2021). CNN reporters were under strict censorship while on the front with the American army being their only source of live information (Osowski, 2011). So everything spectators got to know about the war was in the form of “propaganda imagery” broadcasted by CNN. People did not see the 'real' war, but a 'told' and 'imagined' war (Van Doorn et al., 2021). This ‘imagination’ of the Gulf War created by CNN’s live broadcasting was so powerful that it sparked a lively debate surrounding the ‘CNN effect’: The idea that real-time communications technology could provoke major responses from domestic audiences and political elites to global events (Robinson, 2002).

The Arab Spring and the Twitter revolution (2010-2011)

Most information during the Gulf War was disseminated by legacy media that traditionally acted as gatekeepers. But during the Arab Spring, the availability of social media provided individuals the opportunity to report on the conflict themselves without professional intermediaries. It has been argued that social media played an important role in organizing as well as documenting the uprisings in the Middle East and Northern Africa. Because of this, the Arab Spring quickly became known as the 'Twitter revolution' or 'Facebook revolution' (Shearlaw, 2016).

On the one hand, this shift of power from the legacy (state) media to social media users was argued to create a more pluralistic and democratic public sphere with a greater variety of actors and sources for news selection and dissemination (Witschge et al., 2016). On the other hand the concept of a 'Twitter revolution' was highly critisized by the revolutionaries themselves. The rise of social media was also argued to create a “battlefield of misinformation, rumors and trolls” (Ghonim, 2016) where it was difficult to verify the credibility and truthfulness of information (Brown et al., 2019).

The invasion of Ukraine and TikTok (2022 - today)

Since the Arab Spring, digital and online media have globally become more accessible due to improved technology and internet connection coverage, as well as lower cost of use. This has dramatically increased the scale and scope of social media and has enabled individuals on the ground in Ukraine to share (real-time) reports from the frontlines. An important new channel through which these reports are shared is TikTok, which provides a rapid dissemination of high quality video content. This means that people across the world can now virtually experience elements of combat with higher detail, quality and quantity than ever before (Suciu, 2022).

TikTok affordances

Introduced in 2016, TikTok - a socio-technological platform where users make, remix, share and view short videos - reached over 1 billion active users in early 2021 (Guinaudeau et al., 2021), making it one of the new centers of global communication (Newton, 2022). Following Blommaert (2020), the addition of TikTok to the hybrid media agglomerate of old and new media has the power to recreate and change society.

TikTok’s algorithm has the notorious power to quickly send users down a ‘rabbit hole’

This transformative power of TikTok is partly due to the new affordances it introduces to its users. One essential affordance at the core of TikTok is the ‘reusable sound’-functionality, which allows users to copy the sound of a TikTok and combine it with a new or existing video. Additionally, TikTok offers many multimodal affordances, like the use of a digital ‘green screen’ and an automatically generated voice over. Additionally, TikTok’s logic is defined by the recommendation algorithm for the ‘for you page’, which has the notorious power to quickly send users down a ‘rabbit hole’ based on how long they linger on certain content (Wall Street Journal, 2021).

As new affordances always do, these offer new possibilities and opportunities along with new risks and dangers concerning information disorder (Messaris, 2012). This traditionally invites the development of new media literacy practices. As we will see, media literacy policy is imposed in a top-down, macro-level, overt, explicit manner by TikTok. In addition, media literacy practices are developed based on real uses and challenges faced by the users of TikTok. In what follows, we aim to provide a general overview of this media literacy landscape during the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Top-down media literacy policies on TikTok

When using TikTok, people are not just subjected to the traditional top-down media literacy policies that they may face in everyday life, like those imposed on them by states and educational systems. TikTok as a platform also implements media literacy policies in a top-down, explicit and overt manner. These efforts have been intensified since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Early in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, TikTok claimed to take action against information disorder on their platform. They did so by initiating new functionalities and policies, as well as by reiterating existing ones (TikTok, 2022). For example: In addition to partnering up with several independent fact-checkers (e.g. AFP, PolitiFact, DPA), TikTok partnered up with the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) to encourage TikTok users to develop their media literacy, which they describe as “having the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication” (TikTok, 2022).

TikTok users are encouraged to be aware of the sources of the information they encounter

In 2020, TikTok and NAMLE already launched the “Be Informed” video series, in which TikTok influencers teached users to “Question the source” and “Question the graphics”, among other things. (TikTok, 2020). On 26 February 2022, two days after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, TikTok posted five new videos in a series titled “Digital Literacy 101”. In these video’s, users are (again) encouraged to be aware of the sources of the information they encounter and to analyze content in order to verify its reliability and truthfulness.

Figure 1: screenshot from a TikTok video from the ‘Digital Literacy 101’ series posted by @tiktoktips (2022), including comments on the right

Bottom-up media literacy practices on TikTok

For a bottom-up approach to media literacy on TikTok, we turn to its users. For them, the affordances that the platform offers could both make them more vulnerable to and better protected against information disorder at the same time (Messaris, 2012). The affordances can be exploited by users to sophisticatedly disseminate information disorder. But also to develop new media literacy practices that can be deployed to detect and debunk this information disorder in new ways. During our analysis, we identified roughly three kinds of users that develop media literacy practices on TikTok. We distinguish between regular users, native semi-professionals and migrated professionals.

Regular users

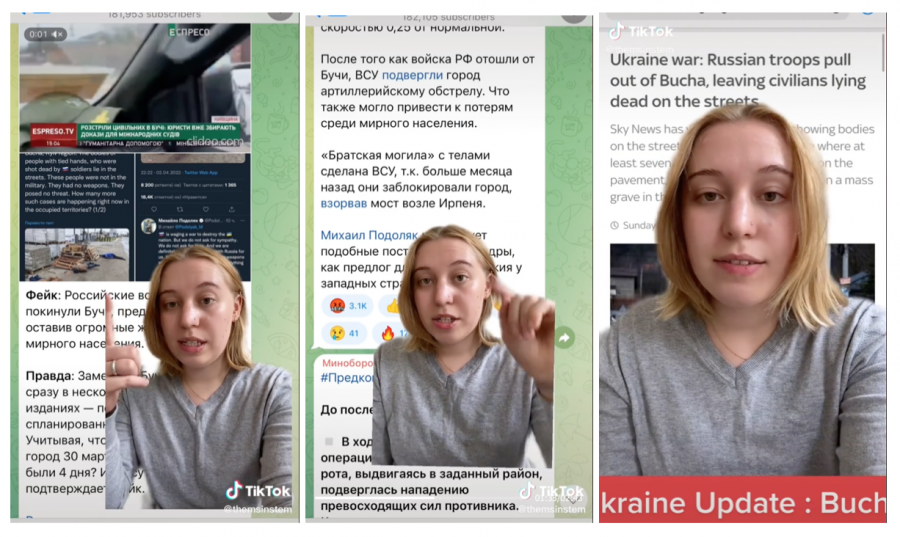

Regular users are non-verified users that use TikTok in a non-professional manner. They develop both general and TikTok-specific media literacy practices in a micro-level, covert, implicit manner, as described by Johnson (2013). An emblematic example of one such regular user is Ksen (@themsinstem), who has dedicated their TikTok account to translating Russian state media. In their TikTok videos, they make liberal use of the ‘green-screen’ functionality, which allows them to project screenshots of (Russian) media outlets behind them and point to certain points of interest, like discrepancies and lies in a Russian texts. In doing so, Ksen implicitly teaches her viewers how to spot a lie in Russian state media and how to discredit such lies by consulting independent news sources.

Figure 2: screenshots from a TikTok video posted by @themsinstem (2022)

Native semi-professionals

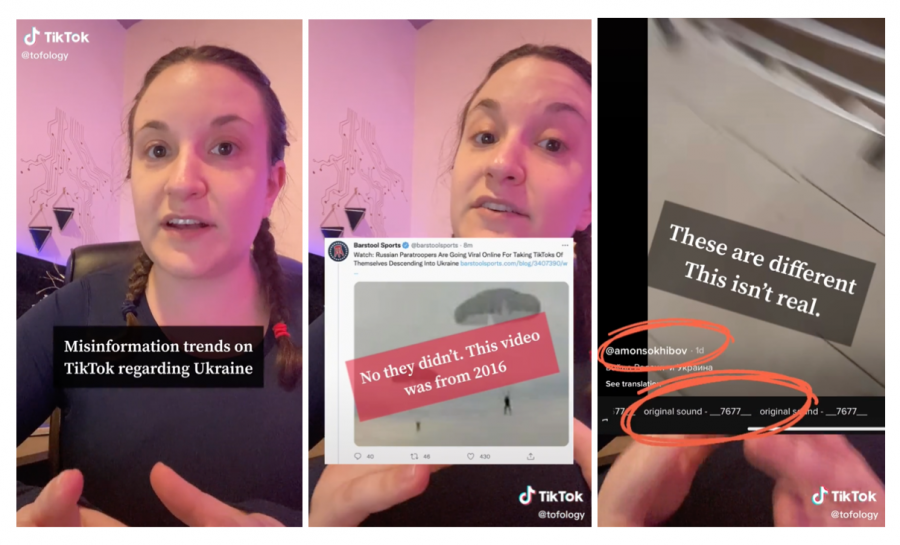

Native semi-professionals are users that have risen to popularity on TikTok because of their insights and expertise regarding information disorder, without having a notable pre-existing following outside of TikTok. They distinguish themselves from regular users by developing media-literacy skills in a professional, overt, explicit manner and reach a sizable audience doing so. In that sense, they more closely resemble top-down institutions, rather than bottom-up users as described by Johnson (2013). An emblematic example of a native semi-professional is Abbie Richards (@tofology), who has come to be one of the best known dis- and misinformation researchers native to TikTok.

In one video, Richards points out misinformation trends on TikTok regarding Ukraine. She attempts to explain how misinformation is spread on TikTok by explaining the inner workings and dynamics of TikTok, like the (imagined) reasons the algorithm ‘pushes’ certain content. In this video, she also gives explicit media literacy advice to her watchers that aligns with the media literacy lessons TikTok shares in their own media literacy efforts, saying “make sure the audio is from the video that you’re watching” and “stay calm and stay skeptical” (@tofology, 2022). In her videos, Richards primarily makes use of the TikTok affordances that lets users display text, pictures and line drawings on top of their videos.

Figure 3: screenshots from a TikTok video posted by @tofology (2022)

Migrated professionals

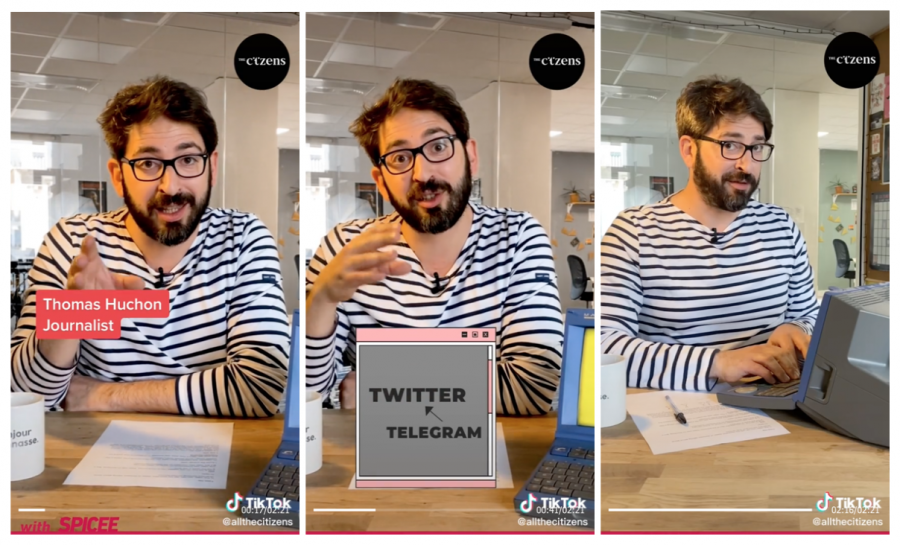

Finally, there are what we dub ‘migrated professionals’. These are users that already concerned themselves with information disorder outside of TikTok and migrated their expertise to this new platform. In this category we mostly find academics and journalists, like Thomas Huchon, a French journalist who made a video for the TikTok account of All the Citizens (@allthecitizens).

In this video, Huchon dives into a case study of information disorder surrounding the conflict in Ukraine in order to explain the concept of a ‘false flag’. He does this by explicitly showing how he, as a journalist, debunks information disorder by analyzing metadata and information flows. In doing so, he implicitly shows that the viewers of this TikTok can do the same if they want to verify information. In their videos, All the Citizens makes little use of TikTok affordances, instead opting to record and edit their video outside of the platform.

Figure 4: screenshots from a TikTok video posted by @allthecitizens (2022), featuring journalist Thomas Huchon

Counterproductive media literacies

Now that we have mapped the landscape of media literacies on TikTok, we should note that these top-down literacy policies and bottom-up literacy practices face a difficult challenge embedded in the logic of TikTok. The platform is known for its aggressive algorithm that composes the timeline of users. Even though the exact workings of this algorithm are undisclosed, research by The Wall Street Journal (2021) has indicated that this algorithm uses watch time as its most valued metric, which can quickly lead users down a ‘rabbit hole’. The longer a user lingers on a video on TikTok, the more likely the algorithm is to provide the user with similar videos.

Lingering on a TikTok in order to scrutinize it might counterproductively lead to more information disorder on their ‘for you page’, rather than less

This means that, when users adapt the media literacy policies implemented by TikTok and practices shared by other users - which mainly focus on critical evaluation of content -, they might encourage ‘their’ algorithm to provide them with content similar to the content which’s truthfulness and reliability they question. TikTok encourages users to analyze content. Abbie Richard advices her followers to stay calm and critical. But if that means lingering on a TikTok in order to scrutinize it, it might counterproductively lead to more information disorder on their ‘for you page’, rather than less.

Conclusion

After the introductions of live television coverage during the Gulf War and user-generated content on social media during the Arab Spring, TikTok seems to be the next defining medium during the Ukraine conflict. With this article, we aimed to provide a general overview of the top-down media literacy policies and bottom-up media literacy practices developed on TikTok aimed to apprehend (new forms of) information disorder surrounding the current conflict.

This overview indicates that TikTok’s top-down efforts and the bottom-up practices developed by users generally adopt a similar message: TikTok’s affordances enable (new forms of) information disorder and users should be critical, skeptical and analytical of the content they consume and produce. This message, however, is at odds with TikTok’s own algorithm, which might send users down a ‘rabbit hole’ due to long watch times resulting from a critical reading of content. In the case of the 2022 Ukraine conflict, actively practicing media literacy and examining the reliability of content could in fact lead to a timeline increasingly filled with (possibly misleading) war footage.

References

All the Citizens [@allthecitizens]. (2022, April 13). 🚨 Conspiracy theory alert! From ‘false flags’ to metadata, watch journalist Thomas Huchon debunk a piece of #fakenews about [TikTok video]. TikTok.

Blommaert, J. (2020, June 19). Jan Blommaert on “Old new media” [Video]. YouTube.

Brown, H., Guskin, E., & Mitchell, A. (2019, December 31). The Role of Social Media in the Arab Uprisings. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Ghonim, W. [TED]. (2016, February 4). Let’s design social media that drives real change | Wael Ghonim [Video]. YouTube.

Guinaudeau, B., Votta, F., & Munger, K. (2021). Fifteen Seconds of Fame: TikTok and the Supply Side of Social Video. Unpublished.

Johnson, D. (2013). Language Policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, T. (2017, April 19). Desert Storm: The first war televised live around the world (and around the clock). Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2019). Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388.

Messaris, P. (2012). Visual “Literacy” in the Digital Age. Review of Communication, 12(2), 101–117.

Mihailidis, P., & Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable Spectacle in Digital Culture: Civic Expression, Fake News, and the Role of Media Literacies in “Post-Fact” Society. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(4), 441–454.

News Literacy Project. (2022, March 28). Combating disinformation about the war in Ukraine. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Newton, C. (2022, March 18). The vibe shift in Silicon Valley. By Casey Newton. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Osowski, M. (2011, March 28). To what extent was the US military’s attitude towards the media during the 1991 Gulf War a product of its experience in Vietnam? E-International Relations. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Richards, A. [@tofology]. (2022, February 25). n.a. [TikTok video]. TikTok.

Robinson, P. (2002). The CNN Effect: The Myth of News Media, Foreign Policy and Intervention (1st ed.). Routledge.

Shearlaw, M. (2016, January 26). Egypt five years on: was it ever a “social media revolution”? The Guardian. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Suciu, P. (2022, March 2). Is Russia’s Invasion Of Ukraine The First Social Media War? Forbes. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

@themsinstem. (2022, April 3). #ukrainerussia #slavaukraine #bucha #russiaukraine #notowar #breakingnews #SixNationsRugby #russiaukraineconflict #ukrainerussiaconflict #news [TikTok video]. TikTok.

TikTok. (2020, November 5). TikTok’s “Be Informed” series stars TikTok creators to educate users about media literacy. Newsroom | TikTok. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

TikTok. (2022, April 12). Bringing more context to content on TikTok. Newsroom | TikTok. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

TikTok Tips [@tiktoktips]. (2022, February 26). When evaluating content, ask questions like “Can I trust this source to tell me the truth?" #digitalliteracy #BeCyberSmart [TikTok video]. TikTok.

van Doorn, M., Duivestein, S., Pepping, T., van Doorn, M., & Keen, A. (2021). Echt nep. Bot Uitgevers.

Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). Investigation: How TikTok’s Algorithm Figures Out Your Deepest Desires. WSJ. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

Wardle, C. (2019). First Draft’s essential guide to understanding information disorder.

Witschge, T., Anderson, C., Domingo, D., & Hermida, A. (2016). The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism. SAGE.