Brexit and online political activism

On vox populism, slacktivism and online intertextuality

This paper engages with political online behavior in the Digital Age: does this online behavior have negative consequences? What was the role of vox populism, slacktivism and online intertextuality in the Brexit referendum?

Introduction

Communication networks enable political organization and expression through web platforms that provide information, media hosting, and direct interaction among activists. NGO’s and social movement organizations use these networks to personalize the pathways to popular engagement with their issues (Bennett, 2012).

One might jump to the conclusion here that due to this social fragmentation and increasing individualism, the voice of the people is stronger now than ever. However, some developments in the digital landscape, which at first sight seem to be in favour of a more direct democracy, in fact turn out to be more of a curse then a blessing to the representativeness of the public debate.

In this paper, we will discuss three of these developments in the context of the recently held Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom – vox populism, slacktivism/clicktivism and intertextuality.

Brief background of the Brexit referendum

On June 23rd, 2016 there was a referendum in which all citizens of the United Kingdom were allowed to vote. This referendum is called the ‘EU referendum’ or the ‘United Kingdom European Union membership referendum’ as it deals with the question whether the UK should leave or remain in the EU.

In January 2013, David Cameron promised in his 2015 election campaign to renegotiate the EU membership and later hold a referendum, should the Conservative Party win a parliamentary majority at the general election. When the Conservatives won a majority in the House of Commons in May 2015, David Cameron proposed to hold an “In-Out” referendum by the end of 2017, but only after negotiating a new settlement for Britain in the EU.

On February 20th, 2016 Cameron, now Britain’s prime minister, set June 23rd as the official date for the EU referendum. His announcement followed an extensive renegotiation of the current situation of Britain’s membership at a summit in Brussels. Cameron stated that he strongly believes in the benefits of continued EU membership.

Other Members of Parliament, including London’s mayor Boris Johnson and leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party Nigel Farage, pledged support for the “out” campaigners. The two campaigns that have formed the official lobby groups “Britain Stronger in Europe” and “Vote Leave” set out their positions on five main topics that would form the basis for the referendum. These topics are: trade, EU budget, regulation, immigration and influence.

Vox Populism

Mainstream institutions such as political parties have found that personalized appeals to independent voters can help to engage them (Bennett, 2012). When these institutions make use of the same communication networks to appeal to their audiences, the question then remains to what extent one still can speak of ‘the voice of the people’, in which ‘the people’ represents an independent and individual given.

Vox Populi: the voice of the people?

During the 1990s, political parties defined a distance between 'politics' on the one hand, and 'people/citizens' on the other hand. The ‘old’ political system of representation and especially civil society and the unions were redefined as the gap between politicians and civilians. Politicians were claimed to have become alienated from the needs and aspirations of the people (Blommaert, 2001). A demand for direct participation came up; the voice of the people had to be directly read, heard and spoken by policy makers. The importance of 'vox populi' (the voice of the people) was on the rise and opinion polls became the most popular form of social science research. These polls functioned as an instrument for determining the legitimacy of policies.

The rise of the ‘referendum’ is consistent with this: political decisions have been given a new legitimacy by the image of the 'public opinion' as a determining factor in politics. The quest for public opinion should result in a better democracy, one that takes into account what the citizen feels, wants, demands, claims, and directly tries to tap into this source without interruptive steps. People are claimed to be self-sufficient, 'mature' and confident about in which direction they want to go, and a legitimate policy must follow here. People should be free and able to stand up for themselves and society should have an individualistic foundation; these are classic ingredients of a popular ideology of our society (Blommaert, 2001).

The presence of a public opinion is assumed, but what it looks like and whose public opinion it is often remains obscure. When does one speak of 'support'? If a majority of the population is behind a proposal? Barriers of class, education, ethnicity, gender and age continue to be relevant here. In practice direct democracy is quite often a matter of who brings enough people to the table. In addition, fact and imagination are mixed up. Political parties invest in political communication and the opposition battle makes it possible for them to do this in a particularly radical and unrealistic way (Blommaert, 2001). Mass media take time to look into these fantasies, and a variety of definitions, texts, images and policies will occur. When one accepts these discourses and images as a reality, this creates a problem.

“Online platforms can be used as instruments to create legitimisation for a certain political project.”

Online comments should therefore not be seen as a presentation of ‘the public opinion’, but should be investigated as part of a political-ideological battle; as potential manipulations aimed at the public opinion and the views of journalists. Online platforms can be used for the construction of an idea of ‘the public opinion’ and as instruments to create legitimization for a certain political project (Maly, 2016). Already in the nineties, Thompson pointed towards media as one of the primary sites of ideology production. This is particularly true for the new domain of ideology production processes that have occurred since the rise of the internet.

Social media are full of political talk and ideological battle to legitimize certain policies. That means that we cannot understand these policies without taking into account new domains for political activism. Social media are used for manipulation, and in that sense a potential threat can be seen for the quality of democracy and the democratic debate. These manipulations can feed a vox populism (Maly, 2016). If one political party succeeds in dominating an online platform, then they can claim that they alone speak in the name of the people.

Vox populism in the Brexit discourse

Focussing on Facebook alone, the most ‘liked’ page of a British political party is not the UK Independence Party (Ukip, 554.319 likes), it is not the Conservatives (554.573 likes) or the British National Party (205.887 likes), nor is it The Labour Party (442.493 likes). It is Britain First (1.339.464 likes). This far-right political movement first caught attention in 2014 through several well-publicised stunts, such as invading mosques and driving in military armoured cars. From the beginning of its existence Britain First has been active to create a presence on social media.

Figure 1. Examples of Brexit memes as found on the Facebook page of Britain First

The party’s rapid growth on social media gave the impression that there is a massive street movement afoot in the United Kingdom. However, a report by advocacy group Hope not Hate estimated that less than a third of Britain First’s Facebook followers were genuine supporters (Withnall, 2015). People are simply being lured to click and like the page through colourful memes, quotes by for example Winston Churchill and George Orwell, and statements on popular issues such as Brexit (figure 1).

Britain First posts more frequently on its Facebook page than any other British political party; however the individual posts generate considerably fewer likes than posts by other parties (Goodway, 2014). Still, when they reached 1 million likes on their page last year, Britain Frist boasted of the milestone on its website claiming “genuine popular support of its ideals, policies and views” (Withnall, 2015).

Yet, Britain First seems to struggle to maintain its following offline. In November 2014, despite the large following on social media (their page had around 500.000 likes on Facebook back then) and chairman Paul Golding’s assertion that the group had at least 6.000 official members, Britain First only managed to gather 60 of those people on a march through Rochester in Kent in support of its candidate, and only 1.300 people were willing to fill in an email complaint to the British Channel 4 (Collins, 2015).

Britain First was founded in 2011 as a Christian movement and protest group by Jim Dowson, a Belfast-based Protestant businessman and former member of the British National Party. In 2014, Dowson quit the group claiming that he was shocked to discover that Britain First was full of “racists and extremists”. His successor, Paul Golding, decided that Britain First is now the self-appointed defence force of the UK Independence Party. Britain First includes a lot of the same people that Ukip’s politics attract, so there is not much Ukip can do (Collins, 2015).

In their research on government’s responsiveness, Dekker and Bekkers (2015) pointed out that responsiveness to the virtual public sphere can be an advantage in terms of democratic legitimacy and relevant from a more strategic point of view. Too much political responsiveness is however undesirable as an unstable environment will undermine the functioning of the policy field. When a system is only responding to its external context of public preferences without formulating long-term policy objectives, it will be only short-lived. Policymakers need to be responsive to external claims while continuously pursuing more long-term goals.

Slacktivism/Clicktivism

Since the launch of the Internet and social media, many aspects of our social life have been transferred to the digital sphere. Therefore, it comes as no surprise to see political discourses and activism online. Instead of walking the streets with banners or occupying squares, political involvement is staged online. This digital dimension as well as social media in general have changed political engagement due to the unparalleled environment of communication and information distribution which the Internet provides (Halupka, 2014: 115) and turned it into a more visible, fast and intertextual form of communication and participation.

Some critics claim that this new form of online political action is not about actual committed participation but solely about clicks and feeling good about oneself which lead to criticising Internet activism as slacktivism/clicktivism (Morozov, 2011). However, this academic discourse has been challenged with an understanding of Internet activism as enabling for the users and as a new form of political action on a digital scale. Although it might include a feel-good emotion it can still be considered political activism.

In the following we will look into slacktivism in general by explaining two possible definitions of slacktivism as either “easy”, feel-good activism and impulsive and non-committed new form of political action. The “Brexit” discourse will serve as context for this. We will then discuss memes and mashups, which are often “labeled as clicktivism when their content adopts a political tone, or are used to express a political view” (Halupka, 2014: 128).

Political engagement has been enabled by and reinvented in the digital sphere. Every individual nowadays has the possibility to act and react upon political issues autonomously on social media networks. Twitter, Facebook and co. have provided “unseen possibilities for distributing and redistributing information on ongoing campaigns and expressing political preferences to friends and family” (Christensen, 2011). New technologies have simplified the process of acting upon politics which has led to critics condemning online activism as a simpler, lazy and convenient alternative to the legitimate and arduous tradition of political engagement (Halupka, 2014: 115-116). Slacktivism is seen as the outcome of the “multiplicity of possibilities and the easy availability of quick spiritual and intellectual fixes” which causes a lack of ´real` commitment (Morozov, 2011: 185).

Slacktivism involves acts such as “liking” on Facebook, signing a petition, changing your profile picture or sharing online content with others. Due to its ease slacktivism is a reaction to political discourses and content (Halupka 2014: 119) and people can like many things at the same time with the same enthusiasm. There seems to be not enough time to deeply commit to anything, and the Internet provides a way in which one does not need to invest much time or effort and still has the chance to participate. In this sense, individuals who perform acts of slacktivism do so in order to “exercise a sense of moral justification without the need to actually engage” (Halupka 2014: 117). This alleged intention behind online activism leads to a lack of commitment and effectiveness.

There is also the criticism that activities seen in the virtual sphere “may make the active individual feel good, but have little impact on political decisions and may even distract citizens from other, more effective, forms of engagement” (Christensen, 2011). At the same time, it may draw people on to Internet activities who otherwise would have engaged in traditional ways, seeing the quantity of political engagement from others and mistake quantity for quality (Morozov, 2011: 187). The Internet platform “merely provides another tool for the already active; it does not help mobilize previously passive citizens” (Christensen, 2011), claim some critics whereas others believe that it does activate more citizens but those increased activities "do not have any impact on political outcomes in the real world” (Christensen, 2011).

Due to the ease of Internet use, a low-risk, low-cost activity via social media has been produced which is used by many individuals, both politically interested and non-interested ones (Halupka, 2014: 117). However, “the means and the outcomes used by slacktivists are insufficient to achieve political goals” (Christensen, 2011). Thus, many critics condemn online activism as an inferior mode of participation and as disposable and noncommittal acts. (Halupka, 2014: 117)

Others argue that online activism cannot be compared to ´real` life activism because it is staged on a different level and is therefore a different form of engagement. This change in political participation is, according to some critics, not a uniform decline in participation, but a diversification of how citizens take part in political matters (Christensen, 2011). Max Halupka defends slacktivism as a political act that is a “reactive gesture” (2014: 119) and is carried out spontaneously. He argues that slacktivism is a form of political engagement which should be understood “as a response to, and engagement with, an established political Object” (Halupka, 2014: 121). The relation with the political cause is still present; however, the engagement part is based on a reflexive action (Halupka 2014: 121). This makes it an advanced and new form of political activism which has a number of features, such as: situated online, impulsive gesture, noncommittal, not drawing upon specialized knowledge, easily replicated, engaging with a political object, and an action performed (Halupka, 2014: 124-125).

Slacktivism has become a popular keyword when it comes to political online activism. A clear definition on whether or not expressions online amount to political participation or not does not exist. However, a common understanding is that those expressions online are still “expressions of political preferences” (Christensen, 2011). These expressions can be demonstrated through various digital forms such as online petitions, online voting, social media interaction with memes or mashups. The disagreement is on whether or not these political expressions online can be considered a new form of participation or lazy, feel-good activities. On the one hand critics argue that the Internet and social media enable users to easily and quickly participate, creating a new structure of impulsive and easily replicated action (Halupka 2014: 125). On the other hand, this simplification causes a lack of commitment, ineffectiveness and moral justification among users.

In the case of Brexit many forms of slacktivism have been seen on Facebook and Twitter, such as the act of signing petitions, creating awareness, sharing images, videos or creating memes and mashups. Figure 2, 3 and 4 show cases of “Brexit” activity where a form of slacktivism is required. The next section will look in detail into memes and mashup and explains why this phenomenon is a direct consequence of the changing forms of political activism and an igniter of slacktivism.

Figure 2 & 3: Online petition posted on Facebook

Figure 4: Shared on Twitter

Online Intertextuality

Intertextuality was a term first used by Julia Kristeva. She introduced the concept of loose texts which include “traces of and tracings of otherness, since they are shaped by the repetition and transformation of other textual structure.” (Alfaro 1996: 268) Intertextuality is “the reference to or application of a literary, media, or social ´text´ within another literary, media, or social ´text.´” (Lemaster 2012) “Texts” from one medium are transferred to another medium and thereby create a fusion and intertextual product.

Digitalization has taken intertextuality to a new multimedia level and to new forms of communication and information distribution. The Internet and social networks do not only enable users to pursue their interests autonomously but also intertextually. Expressions online can be delivered in multiple forms and varieties, containing the possibility of more attractiveness and visualization and thus virality. Producing communication and information items with a great scope and speed is the goal of Internet products. Activists use intertextuality to connect and communicate with as many people as possible.

Intertextuality can be used to attract more people and thus is used by many. In online activities this is mainly seen in the shape of memes and mashups. Internet users use memes and mashups to evoke an immediate connection, humour or empathy. This usage goes hand in hand with slacktivism as there is an interplay between those two. Memes and mashups can help create affinity and therefore can be seen as igniter for slacktivism.

Richard Dawnkins coined the term “meme” “by analogy with “gene” as “small cultural units of transmission (...) which are spread by copying or imitation” (Varis and Blommaert, 2014: 8). Internet memes can spread quickly from person to person in a culture, mostly in form of mimicry, and are used to transform a certain message in an easy and catchy way to generate attention. This form of information transmitting is mostly seen among individual Internet users who address a popular cultural, political or social issue. “Brexit” is no exception and because the topic of the EU referendum has been discussed for a long time many intertextual items are circling around on social media platforms, mostly posted by individuals but sometimes also used by political campaigns. Let us look at some of the most popular ones which include image macros, sign holding, GIFs and video mashups among others.

One famous meme that has been viral for a longer time is the British World War II Propaganda poster, here seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Examples from Twitter and Facebook

This meme

“can be identified as intertextually related by the speech act structure of the message (an adhortative ´keep calm´ or similar statements, followed by a subordinate adhortative) and the graphic features of lettering and layout (larger fonts for the adhortatives, the use of a coat of arms like image)” (Varis & Blommaert, 2014: 9).

This meme draws its visual architecture and the speech act from the original which provides a memic-intertextual recognisability (Varis & Blommaert 2014: 11). Placing these two elements in another context helps approach a new and different audience and give the meme a new purpose and use while at the same time remaining clear, understandable and recognizable for everyone.

Other memes found on Facebook or Twitter relating to the topic of “Brexit” are image macros. Those feature a mostly well known image and capital lettering on top and on the bottom of the image. The layout remains the same, only the image and content of the text are substituted, which can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Examples of image macros from Facebook and Twitter

Furthermore, the meme of “sign holding” has since 2011 been actively used for social or political causes. This refers to either taking a selfie or posting a photo with a hand-written sign that states your mission, wishes, concerns or opinion. A hashtag is often included so that other people can share their own, similar picture and an online community emerges. This meme gives face to different voices and is highly used by the “StrongerIn” campaign in Britain as seen in Figure 7. On social media, pictures are worth more than words, in the case of Twitter for instance also because the amount of text in a tweet is limited. In this particular meme, text and photo is combined and the political purpose is personalized.

Figure 7: "Sign holding" memes from Twitter

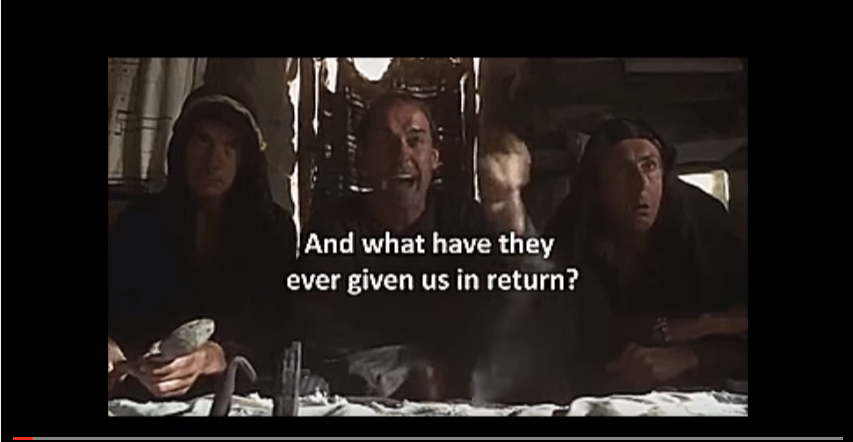

Next to these memes there has also been popular mashup concerning “Brexit”. A mashup is a product of two or more different sources, mostly a text or a speech and a movie or music. These are combined in a satirical or funny way which can also be understood as intertextual criticism of current political issues. Figures 8 and 9 are snapshots from two videos. Both hint towards Monty Python’s movie “Life of Brian”. The first example simply shows the original scene and mutes the voices. Subtitles emerge with the discourse of “Brexit” opponents answering the question “What have they (the EU) ever given us?”.

Figure 8: Scene from “Life of Brian on the EU”

The other mashup video is on the topic of the European Convention on Human Rights. It can also be considered intertextual because the original structure of the scene itself, as well as the structure of the speech act remains the same in the mashup – that is, one allegedly powerful leader, furious about an issue and stating a certain party has never done anything for them, addresses his colleagues to inflame a discussion, followed by the replies of his colleagues.

Figure 9: Scene from the European convention of human rights sketch

Although there are many other memes and mashups on social media concerning “Brexit”, these two have been the most used and spread ones. The memes and mashups we could find on Facebook and Twitter follow the same pattern. All of them operate “via a combination of intertextual recognizability and individual creativity”, hoping to spread a message and ultimately go viral with the adapted version (Varis and Blommaert, 2014: 15). They use recognisability, humour and visual attraction to spread a political discourse. Although memes and mashups require a certain form creativity from their producers, they remain types of activity performed in front of a computer which is on the hunt for “likes” or “followers”. In this context, memes and mashups seem to inspire slacktivism and are part of a changed political participation system.

Conclusion

Digitalization results in new ways of information and communication distribution. By enabling individuals to spread their own words and opinions in social networks, individualism as a modal social condition has been created. Everyone is able to connect easily and effortlessly with a community and represent their stances. This phenomenon can be considered ground-breaking as social network systems give a voice to potentially every single person and enhance a more direct democracy.

However, our paper shows that political online behaviour as an outcome of the digital age has its negative consequences. Instead of people raising their voices to engage politically, vox populism occurs and with it the attempt to legitimize certain policies. Certain political organizations try to ´rule` the ideological-political battleground that is social media by producing easily likeable and clickable content. Online activists interact with this online content in an impulsive and self-justifying manner, labelled as slacktivism or clicktivism. Inflamed by intertextual content, such as memes and mashups, slacktivism is being regarded as either an inferior and lazy form of activism, or a new advance and online version of political engagement. Moreover, intertextuality is being used by both political organizations and individual activists who want to share political discourses multimedially and most of all in a visual way, as this kind of content is the most clicked on, liked, followed and reproduced type of content, and thus evidently has the potential to go viral.

These three developments in the digital sphere are examples of the negative aspects of digitalization and online activities. Vox populism, slacktivism and online intertextuality can be said to have had an adverse effect on the representativeness of the public debate in general and in the case of Brexit in particular.

Literature

Alfaro, M.J.M. (1996). Intertextuality: Origins and Development of the Concept. Atlantis.18,(1/2), 268-285.

Bennett, W. L. (2012). The Personalization of Politics: Political Identity, Social Media and Changing Patterns of Participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 644(1), 20-39

Blommaert, J. (2001). Ik Stel Vast. Politiek Taalgebruik, Politieke Vernieuwing en Verrechtsing. Berchem: EPO.

Blommaert, J. & B. Rampton (2011). Language and Superdiversity. Diversities. 2011, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. , UNESCO. ISSN 2079-6595

Christensen, H. S. (2011). Political activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means? First Monday. 16 (2).

Collins, M. (2015, February 25). The truth about Britain First – the one-man band with a knack for Facebook. The Guardian.

Dekker, R. & Bekkers, V. (2015). The contingency of governments' responsiveness to the virtual public sphere: A systematic literature review and meta-synthesis. Government Information Quarterly. 32, 496–505.

Goodway, F. (2014, October 30). This is how Britain First plans to infiltrate your Facebook feed. The Mirror.

Halupka, M. (2014). Clicktivism: A Systematic Heuristic. Policy and Internet. 6 (2), 115 - 132.

Lemaster, T. (2012). What is intertextuality? Great World Texts.

Maly, I. (2016). The online battle for the Flemish nation. N-VA, banal nationalism and political-ideological activism in cyberspace. Notes on democracy and future research. Unpublished manuscript.

Morozov, E. (2011). The net delusion: the dark side of internet freedom. New York: Public Affairs.

Varis, P. & Blommaert, J. (2014). Conviviality and collectives on social media: Virality, memes and new social structures. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies. 108.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30:6, 1024-1054.

Withnall, A. (2015, November 10). Britain First far-right group claims to be 'first political party' to reach 1 million likes on Facebook.