Telling stories using platform affordances: an analysis on Ben Shapiro’s social media use

Ben Shapiro is a republican, pro-Trump influencer with millions of followers on social media. He, like other political influencers, has discovered ways of using digital platforms to have a voice in the public space by reaching his audience and building his metapolitical stories. In this paper, we analyze how Ben Shapiro exploits social media platform affordances to tell a metapolitical story.

First, we will discuss the concepts of platform affordances and quantified storytelling. Then we will use this theoretical framework to see how Shapiro tells his story on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. In doing so, we hope to get more insight into how using a certain platform can affect the stories that he tells. Ben Shapiro presents a relevant case since he has millions of followers on different platforms. He uses those platforms frequently and successfully, which can provide insights into how technology can be used to construct narratives and gain visibility in the hybrid media system.

Affordances

Over the past few decades, the concept of "affordances" has been popular in a variety of communication technology-related domains. Gibson (1979) was the first to use this concept to refer to an action possibility that is present in a specific environment. He argues that the capacity to act as an actor is an affordance. Building on Gibson’s theory, Norman (1999) argues that there is a distinction between real and perceived affordances. Real affordances are the attributes that an object has or might potentially have. Features that are apparent to the user are called perceived affordances.

There is considerable ambiguity surrounding the use of affordances in communication studies (O’Riordan et al., 2012). Still, it can be a useful analytical tool by offering a comprehensive viewpoint on individual users and technology. O’Riordan et al. (2012) distinguish two categories of affordances: social affordances and content affordances. Social affordances refer to social interaction, whereas content affordances refer to finding and sharing content on these platforms.

It is important to look at how platform affordances and algorithms can influence the meaning of a story told online

During elections, affordances can have different effects on online communication. Jensen and Dyrby (2013) separate the following Facebook features concerning elections: assistance in direct interaction between politicians and voters, projection of a realistic image, and the development of engagement and connection with individuals. Additionally, it is critical to concentrate on the facilitation, projection, and creation goals of political parties.

The concept of affordances emphasizes human perspectives through the online possibilities of several platforms. The relational behaviors that take place between people and technologies are at the forefront rather than the materialistic or constructivist explanations of technology use (Davis and Chouinard, 2016; Evans et al., 2017). Even though the focus on affordances is necessary, Maly (2022) argues that it is not enough to solely look at online interactions. It cannot be fully comprehended without considering the algorithmic and directive logic because it profoundly influences the way we construct meaning. This is why for this research it is important to look at how platform affordances and algorithms can influence the meaning of a story told online. That’s why we also focus on quantified storytelling, which includes platform affordances as well as algorithmic metrics.

Quantified storytelling

Quantified storytelling (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020) departs from the understanding that quantification is integral to sociotechnical platforms. It is through quantification that information can become ordered, made visible, and made known. Quantification, however, is never neutral. Even though numbers carry with them a sense of truth, objectivity, and undeniability (‘the numbers don’t lie’ as many tech companies like to propagate), this is not the case.

The numbers that are made, used, and shown on the platforms under investigation in the current analysis are carefully and meticulously chosen. Data does not ‘just exist’ (“like shells on the beach, ready to be picked up” as philosopher Miriam Rasch (2020) describes it), it is produced and constructed with specific (business) goals in mind. By counting one thing, another thing is not counted. The detached character of quantification – as if it is something that is there whether we are aware of it or not – also invokes the idea that the metrics on socio-technical platforms do not influence us. This also is not the case.

We should understand quantification as a form of meaning-making

The metrics of social media shape future actions by “making [information] valuable within a certain logic of measurement” (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020). Therefore, we should understand quantification as a form of meaning-making. We make something meaningful by quantifying it, and the number or metric resulting from this process of quantification becomes a site of meaning in its own right. In combination with the affordances of specific socio-technical platforms, quantification becomes a potent ingredient for stories to tell on social media. Numbers are incorporated into the complex, contextualized, co-constructed narratives on social media (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020). As we will see, Ben Shapiro is no exception in this regard.

Georgakopoulou et al. (2020), describe three types of metrics on social media: 1) content metrics – numbers as part of what the story is about; 2) interface metrics – numbers we see in social media – likes, retweets, etc.; 3) algorithmic metrics – numbers used by platforms to algorithmically organize users and content, invisible to users. Quantified storytelling “implies storytelling across all three levels: stories about/with numbers using content metrics, numbered story responses relying mainly on interface metrics and the algorithmic shaping of stories and their circulation” (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020). In the current analysis, we thus examine how Ben Shapiro applies and uses quantified storytelling across all three levels to tell a metapolitical story.

Multimodal discourse analysis

For this research, we focussed on social media posts from Ben Shapiro during the 2022 US midterm elections. We specifically chose this moment because quantification becomes extra potent during an election, which revolves around polls, votes, census data, etc. On November 9th, 2022, when the election results were still pending, we took 50 screenshots of Shapiro’s posts on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. These include 19 Facebook posts, 19 retweets, 2 original tweets, 6 retweets, and 4 Instagram Stories.

With our focus on affordances and quantified storytelling, we subjected the screenshots to multimodal discourse analysis (Kress, 2010). This method looks not just at how individual modes (text, picture, uptake metrics, etc.) communicate, but also at how they interact with one another to create meaning. A multimodal approach respects the meaning-making characteristics of quantification and allows us to analyze how metrics - which flow from platform affordances - construct, recontextualize, and give (new) meaning to messages.

The design, features, and affordances of social media allow for quantified storytelling to take place on the levels of content metrics, interface metrics, and algorithmic metrics (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020). In our studied data, we see Ben Shapiro operating on all three levels in order to tell and spread his metapolitical stories. In the following sections, we analyze how Shapiro does this on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Ben Shapiro's stories on Facebook

Facebook can be considered a platform where connecting is embraced and where most posts are indirect. When we look at Shapiro’s use of affordances on Facebook, it is notable that he and his team running the page mostly share links from his blog The Daily Wire for engagement, sometimes along with a short explanation from himself to boost the engagement. Occasionally he does not even add an explanation to his shared links from The Daily Wire. Shapiro uses this social media platform frequently, by posting approximately four times an hour or more. His posts reflect his Republican political views.

We don’t always see literal numbers in Shapiro’s social media posts. This is especially true in the links to The Daily Wire he posts on Facebook. Still, we can consider a lot of his posts as part of quantified narratives. When a link is titled “John Fetterman Wins Hotly Contested PA Senate Race Against Dr. Oz: Projection” (Shapiro, 2022b), or “Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer Hangs On Despite Late Republican Surge: Projection” (Shapiro, 2022a), words like ‘wins’, ‘hotly contested’, ‘hangs on’, ‘late republican surge’ and ‘projection’ (when referring to a calculated expectation based on probability and statics) index a process of quantification.

It is notable that he does not fully utilize the affordances Facebook offers to engage with an audience. For instance, he does not engage by responding to questions or engaging in debates and discussions (Jensen & Dyrby, 2013). One of the examples where he does post a link with a short explanation is the post about Emily Ratajkowski and her son. She buys her son a baby doll and a tea set, which clashes with Shapiro’s ideology (see figure 1). However, his facilitation starts and stops with that short explanation. There has been no further interaction from Ben Shapiro with the audience of this post.

Figure 1: Shapiro's Facebook post about Emily Ratajkowski

Besides the possibilities of sharing links and interacting with your followers, Facebook also has typical affordances for the users, such as liking, commenting, and sharing. In 2016, Facebook added ‘reactions’ as an extension of the Like Button to give people more ways to share their reactions to a post (Krug, 2016). Reactions include ‘Like’, ‘Love’, ‘Haha’, ‘Wow’, ‘Sad’, and ‘Angry’. Through this feature, Facebook facilitates direct, accessible interaction between Shapiro and his audience.

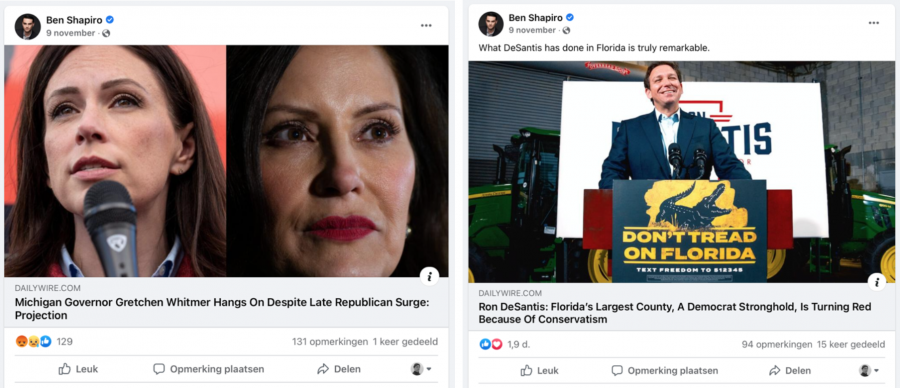

These reactions become potent elements of quantified storytelling, and a perfect example of the co-constructedness of quantified narratives on social media (Georgakopoulou et al., 2020). On Facebook, reactions are visible to all users, so they have the potential to act as a powerful modality that, in interaction with other modalities like text and images, adds meaning to a message. We can see this in two posts by Shapiro on Facebook (see figure 2). A post about a democrat winning in the midterms elections gets mostly ‘Angry’ (> 60) and ‘Sad’ (> 20) reactions (Shapiro, 2022a), while a post about a republican winning gets mostly ‘Like’ (> 1.600) and ‘Love’ (> 250) reactions (Shapiro, 2022c).

Figure 2: Two different posts by Ben Shapiro with negative and positive reactions

Here, we see the power of interface metrics as a site for meaning-making. Shapiro’s followers collectively give meaning to a post via their reactions. As a result, the post gets an extra layer of meaning. Not only do we see that a democrat has won the Michigan midterms, we also see that this is bad news according to ‘the people’. These interface metrics alleviate Shapiro from giving meaning to his news himself, helping him in keeping up his identity as an objective commentator.

Shapiro's power on Twitter

Contrary to Facebook, Twitter is a unidirectional platform where social expectations differ. There is no expectation that the people you follow need to follow you back, as with Facebook. The typical affordances here used by Shapiro and his audience are retweeting, co-tweeting, mentioning, and replying.

These interface metrics are ambiguous. A like, retweet, or comment can have many different meanings. But at first sight, higher numbers do index a certain reliability or popularity of a tweet and the message it carries. This leads to a ‘more is better’ effect for both humans and algorithms. A tweet with a lot of likes is more likely to be picked up by the Twitter algorithms, and thus seen by humans on Twitter (Maly, 2022) and in the hybrid media system, e.g. in newspapers or talk shows.

Within our data, Shapiro retweets considerably more than he actually tweets. In doing so, he is adding to both the interface metrics and algorithmic metrics. Likes, retweets, shares, number of comments, number of followers, and reactions are not only visible to the users of a platform, but they are also used by platforms to algorithmically order and make visible content and social interactions (Bucher, 2018).

By adding his retweet to the count, Shapiro influences the narrative of the tweet

His retweet – as a popular account – could urge the algorithm to push the tweet to a lot more people. This gives Shapiro the power to amplify the message of a tweet without actually adding any content. In doing so, he keeps a certain distance from the content and we don’t know what he thinks of it or why he retweets it. But adding his retweet to the count does influence the narrative of the tweet. It could index credibility for the tweet, it could index Shapiro’s support for the tweet, and it could add to the importance of the tweet in the larger discourse. Of course, it could also result in the exact opposite, depending on people's preconceived notions of Shapiro.

Additionally, Shapiro's retweeting behavior leads to the creation of an information environment. He builds a network of 'good channels' around him. In that sense, a retweet can be interpreted as a 'Ben Shapiro stamp of approval', prescribing the accounts he retweets to his followers and (to a lesser extent) his extended network. Such a retweet can result in a lot of extra exposure for the retweeted accounts, who might reciprocate this exposure, e.g. with a comment under Shapiro's retweet or a mention of Shapiro's account in a new tweet. In the long run, the Ben Shapiro stamp of approval can thus lead to more algorithmic uptake and visibility for Shaprio's account as well.

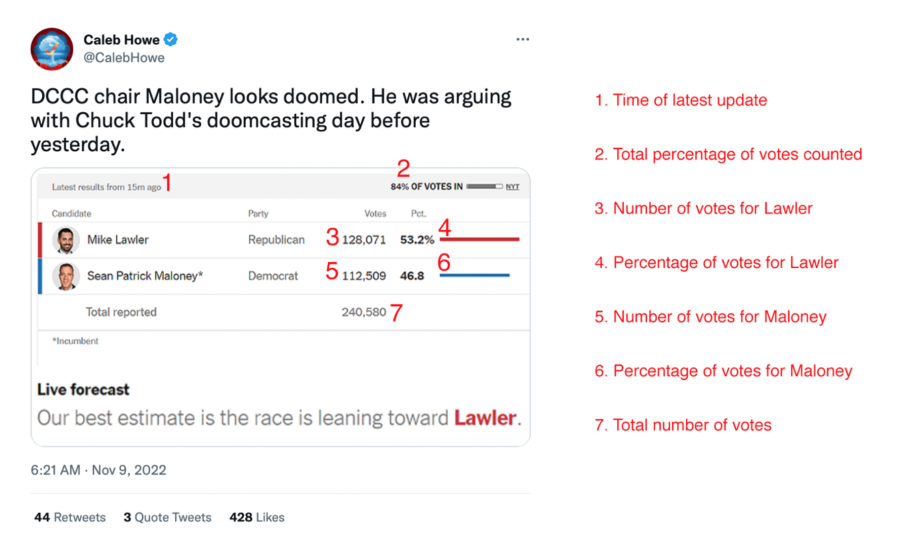

The content Shapiro shares on Twitter tends to be more profoundly about his political opinions. During election time, content metrics play an even bigger role than they regularly do on social media. Democratic elections are inherently quantified (Rose, 1991). They revolve around census data, demographics, polls, votes, flipped states, policy plans, budgets, winners, losers, and more. Ergo, they revolve around numbers. So it is no surprise that we see a lot of content metrics in Ben Shapiro’s content and storytelling on Twitter. Take for example the post by @CalebHowe (2022) he retweeted. In this post we find many content metrics, telling the story of a republican who is winning.

Figure 3: A tweet by @CalebHowe that was retweeted by Shapiro, including content metrics

These content metrics do more than just tell a story. They are also deployed to index the expertise and trustworthiness of Ben Shapiro as a political pundit. After all, reading and interpreting numbers requires specific knowledge and literacy – especially when it comes to elections. By retweeting and writing about election results and projections, Shapiro acts as an intermediary. One can read the ‘raw’ numbers of the elections (which have an air of reliability and objectivity) and interpret their meaning, e.g. interpreting a race as being hotly contested or recognizing a late republican surge. This intermediary role reinforces Shapiro’s self-presentation as a reliable, knowledgeable expert. Especially since many content metrics are presented as 'just facts' or 'the plain truth', i.e. 'the numbers don't lie' - and Ben Shapiro is here to reveal their meaning.

At the same time, the possibility to retweet and quote tweets on Twitter seems to make it more likely that more users outside his direct following may see his posts. However, it is notable that Shapiro does not use hashtags in his posts, which can be used for the same purpose. With the use of hashtags, his tweets can become part of the public feed and make his content more searchable. It is similar to keywords that are used by news websites and blogs. It eventually increases engagement and enhances political activism (Evans, 2016).

The fact that Shapiro (almost) never uses hashtags, makes this seem like a conscious choice not to join larger discourses. Maybe because there his tweet will also encounter uptake by accounts that oppose his metapolitical narrative, which could damage his image. This remains speculative, however, since the data offers no indication as to why Shapiro refrains from using hashtags. Even though he does not use this specific feature of Twitter, Shapiro remains popular on the platform, with over 5 million followers.

Instagram to boost Shapiro's content

Contrary to the other platforms, Instagram focuses on higher levels of visuality with its symbolic expression. In this case, there is a slight shift in affordances: liking, sharing, and commenting can be used. Public sharing is more limited even if viewers can comment and like postings, because it does not provide emotions to react to regular updates like Facebook does (Hase et al., 2022). Shapiro tends to share posts and Instagram stories. The saved stories, called highlights, play a role in stimulating intimate interactions with the audience. One of these saved stories is his 'Third Thursday Bookclub', where he disentangles his perspective on his favorite books. Even though it does not only entail political books, it can still be considered a way to keep the audience engaged. On top of that, Shapiro's Instagram entails several videos about his podcasts and passive posts linked to the Daily Wire. Shapiro tends to use his page to promote and boost the content of The Daily Wire and his podcast. Lastly, Shapiro does not use hashtags for Instagram, just as he does not use those for Twitter.

We have to remember that Shapiro and his team can see more metrics than we can

Instagram is the platform where we see the least quantified storytelling from Shapiro. Even though likes, comments, and shares offer interface metrics that can be deployed for storytelling, we hardly see him doing this explicitly. But we have to remember that Shapiro and his team can see more than we can. As a creator, Shapiro has access to additional metrics (‘Insights’ in Meta lingo (n.d.)), like the reach of a post and the clicks on a story. These insights can give him and his team an idea of what does and does not resonate with their audience. For instance which stories acquire the highest click-through rate to The Daily Wire. This information can help them make the Ben Shapiro ‘brand’ algorithmically more visible on Instagram and other platforms, which they probably hope will eventually lead to more ad revenue and other forms of monetization of visibility, e.g. merchandising. Thus, even though we don't see many metrics on Shapiro’s Instagram account, we can expect him and his team to use the metrics they have exclusive access to fine-tune their marketing and content strategy accordingly.

Quantified storytelling through platform affordances

Our findings indicate that Ben Shapiro knows how to use different social media platforms and their affordances. On Facebook, he shares links to articles and adds short or no text to them. Besides that, he gives followers the possibility to comment and react with different emotions. The different reactions contribute to the story Shapiro wants to tell. On Twitter, Shapiro has found a place where he can retweet posts of others and by that add more meaning to them without writing something himself. His followers on the other hand can also easily share Shapiro’s content which brings his content into new online networks. For Shapiro, Instagram is a place to share videos of podcasts and stories. He uses these stories to create an intimate relationship with his followers.

Looking at our data through the lens of quantified storytelling, we can conclude that Ben Shapiro exploited platform affordances to indulge in quantified storytelling in several ways during the 2022 US midterm elections. He deployed content and interface metrics to index credibility, expertise, and trustworthiness. He co-constructs a narrative with his audience through Facebook Reactions. And he affiliates his own performed identity to content by retweeting it and ‘adding to the numbers’.

As we can see, Shapiro uses several platforms to tell and disseminate his metapolitical stories. But we also see how he uses each platform in a unique and seemingly strategic way. For example, the reactions feature of Facebook and the retweet feature of Twitter lead Shapiro to deploy different ways of (quantified) storytelling. This is not to say that the features of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have deterministic power in the sense that they dictate how Shapiro and his team use these platforms. Rather, the differences in features offer Shapiro different possibilities of action. Herein it becomes clear that we should consider the platforms deployed by metapolitical influencers like Shapiro as actors shaping the stories shared by these influencers through their affordances. Future research therefore cannot ignore the role these (and other) platforms and their affordances play in the narratives created and disseminated by metapolitical influencers in the hybrid media system.

References

Bucher, T. (2018). If . . . Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford University Press.

@CalebHowe. (2022, November 9). DCCC chair Maloney looks doomed. He was arguing with Chuck Todd’s doomcasting day before yesterday. Twitter.

Davis, J. L., & Chouinard, J. B. (2016). Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse. Bulletin of Science, Technology &Amp; Society, 36(4), 241–248.

Evans, A. (2016). Stance and identity in Twitter hashtags. Language@Internet, 13(1).

Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., & Treem, J. W. (2016). Explicating Affordances: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Affordances in Communication Research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(1), 35–52.

Georgakopoulou, A., Iversen, S. & Stage, C. (2020). Quantified Storytelling: A Narrative Analysis of Metrics on Social Media. Springer Publishing.

Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances. Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing, 67–82.

Hase, V., Boczek, K., & Scharkow, M. (2022). Adapting to Affordances and Audiences? A Cross-Platform, Multi-Modal Analysis of the Platformization of News on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter. Digital Journalism, 1–22.

Jensen, T. B., & Dyrby, S. (2013). Exploring Affordances Of Facebook As A Social Media Platform In Political Campaigning. European Conference on Information Systems, 40.

Kim, D. H., & Ellison, N. B. (2021). From observation on social media to offline political participation: The social media affordances approach. New Media &Amp; Society, 24(12), 2614–2634.

Krug, S. (2016, February 24). Reactions Now Available Globally. Meta.

Maly, I. (2022). Algorithms, interaction and power: A research agenda for digital discourse analysis. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 295.

Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions, 6(3), 38–43.

O’Riordan, S., Feller, J., & Nagle, T. (2012). Exploring the affordances of Social Network sites: an Analysis of Three Networks. European Conference on Information Systems, 177-1-177–13.

Rasch, M. (2020). Frictie. Ethiek in tijden van dataïsme. De Bezige Bij.

Rose, N. (1991). Governing by numbers: Figuring out democracy. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(7), 673–692.

Shapiro, B. (2022a, November 9). n.a. Facebook.

Shapiro, B. (2022b, November 9). n.a. Facebook.

Shapiro, B. (2022c, November 9). What DeSantis has done in Florida is truly remarkable. Facebook.

Shapiro, B. (2022d, November 14). So the “let people be whatever they want to be” celebrities now promote forcing their preferences onto their children? The Hollywood hypocrisy is real.. Facebook.

Tandoc, E. C. (2014). Journalism is twerking? How web analytics is changing the process of gatekeeping. New Media & Society, 16(4), 559–575.