The white genocide conspiracy theory

White genocide is a conspiracy theory that has received increased attention in 2020 as the counter-rhetoric of the BLM protests. Often called the ‘great replacement’ theory, it refers to white populations gradually being replaced with non-white people. The causes are said to be mass migration, abortions, low fertility rates, integration policies, as well as diversity and tolerance rhetorics. The belief is shared by famous politicians, influential TV channels, and is often used as a part of far-right populist campaigns.

YouTube videos, Instagram profiles, and white-genocide dedicated websites were studied for this paper. Based on the content freely accessed online, the article analyzes the conspiracy theory, its spread, and offline and online consequences it brings into the world.

White Genocide or Great Replacement theory

The white genocide or the great replacement theory was popularized by French writer and novelist Renaud Camus in his novel Le grand replacement (2011). Ever since it got first published, the phrase Le grand replacement has gained significance and became widely circulated in French political and media discourse (Sexton, 2016). In his novel, Camus stresses that France has been dragged into an invisible war undergoing the total replacement of the country’s population (Sexton, 2016)

The author has tried to prove that by being drawn in mass migration, decreasing birth rates among white Europeans, and multiculturalism, the white population is soon going to lose its dominance in the world (McCann Ramirez, 2020). According to the writer, “[...] we are starting going to put little flowers and little bears — there is some silly childish celebration of le vivre ensemble [living together]. It is precisely le vivre ensemble that kills” (Camus, 2016, Sexton, 2016).

Camus calls for several solutions to save Europe from the supposed white genocide, namely by remigration, which also branches out to more extreme forms of radical political anti-immigration activism and encouragement of white women to have more children (Sexton, 2016, McCann Ramirez, 2020). In some interpretations, anti-white genocide activism can result in violence to the communities of color (Sexton, 2016). As the creator of the conspiracy theory, Camus states: “I think, of course, we are much more colonised than we ever colonised ourselves” (Sexton, 2016, McCann Ramirez, 2020).

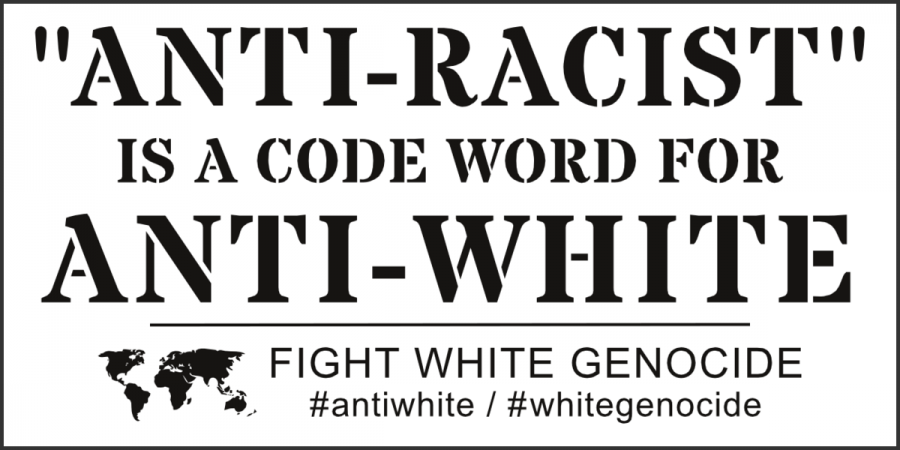

Figure 1: Propaganda distributed in white supremacy blogs online promoting the rhetoric of the white genocide conspiracy theory.

The white genocide conspiracy theory has grown and developed throughout the years attracting new admirers. With time, its traits have appeared in some of the white extremist manifestos published online. Similar rhetoric was also picked up by far-right and white supremacy groups all over the world. Although much of the information explaining the conspiracy theory online gets banned from public access classified as 'racist', activists constantly come up with new creative ways to increase their visibility and recruit more believers.

Often, the followers of the white genocide conspiracy theory have a wide range of related beliefs. Many are convinced that the publicly accepted rhetoric of ‘diversity’ and tolerance is going to bring an end to the white race (McCann Ramirez, 2020). The ‘Blood and Soil’ argument is also often used to defend white people’s rights to exclusively live in certain countries. In light of the 2020 BLM protests, the believers have stated that ‘White lives matter’, too.

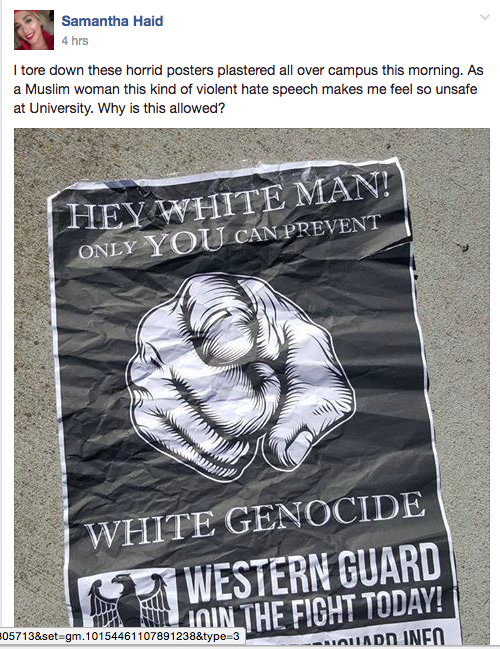

Figure 2: Offline distribution of white genocide-related flyers by far-right activists.

The rhetoric of the conspiracy theory has also been picked up by conservative politicians. For instance, Matt Gaetz, who is a Republican member of US congress, has stated that “[...] Black Lives Matter protests were part of ‘an attempted cultural genocide going on in America right now’" as well as that "the left wants us to be ashamed of America so that they can replace America" (McCann Ramirez, 2020). Donald Trump has also referred to the conspiracy theory in one of his pre-election tweets (McCann Ramirez, 2020).

The white genocide conspiracy theory has influenced media rhetoric. News reports have picked up some of the metaphors regarding migrants as ‘invasion’ and criticizing the position of tolerance advocated by Western political leaders. In the US, one of the most prominent public voices of the great replacement is Fox News. The channel reports “a near-constant stream of claims that America is being subjected to an immigrant ‘invasion’” with over seventy on-air uses of this rhetoric (McCann Ramirez, 2020). Fox’s hosts make use of the conspiracy theory claiming that the evil great replacement plot will remake America, replacing “American citizens with illegals who will vote for the Democrats” (McCann Ramirez, 2020).

Figure 3: The message is framed in accordance to the Russian-speaking media sphere: 'Visible and invisible genocide: poisoned foods, alcoholism, revolutions, Holodomors, religion, GMOs, vaccines, drugs, poisonous medicine, smoking, ignorance, wars'.

Often, the white genocide conspiracy theory gets adopted in accordance with the local context. For instance, in the Russian media sphere, the theory of the genocide of Slavic people is promoted by the far-right. The information distributed on social media blames Western tolerance propaganda, mass migration, and planned parenthood for the decline of the Slavic population. In line with the great replacement theory, radical activists promote ideas of blood purity, the need to preserve the Slavic nation, and gain supporters all over the country based on these ideas (Vdovychenko, 2019).

Figure 4: The great replacement theory gets slightly transformed in the Russian microblog: "Migration? No, it is a genocide of native Russian folks and its replacement by migrants-occupants".

The success of the conspiracy theory

Conspiracy theories are a part of the ‘stigmatized knowledge’ (Barkun, 2016). What it means is that theories, like the one on great replacement, are “knowledge claims that have not been accepted by those institutions we rely upon for truth validation” (Barkun, 2016). The conspiracy theory of the white genocide is spread due to a few factors. Among them are “the ubiquity of the Internet, the growing suspicion of authority, and the spread of once esoteric themes in popular culture” (Barkun, 2016).

The white genocide conspiracy theory has influenced media rhetoric

First and foremost, the spread of conspiracy theories is attributed to the elimination of the gatekeepers, namely between ‘the media’ and ‘the people’ (Barkun, 2016). The Internet has played a vital role in the popularity and growth of the great replacement theory. By now, most of the content spread online on the white genocide is done through private accounts or microblogs. The posts that have appeared on the small YouTube channels or Instagram pages, do not only get Internet visibility, they also get multiple reshares by the users. The reposts give conspiracy theories “the appearance of validity, conferring a kind of pseudo-confirmation” (Barkun, 2016).

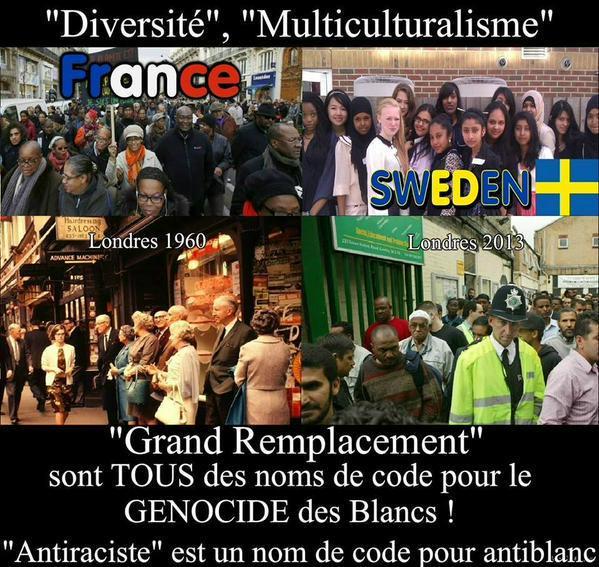

Figure 5: The promotion of the great replacement theory online: "Diversity , multiculturalism, great replacement are all name codes for the white genocide. Antiracist is a code name for anti-white". The meme aims at fueling of suspicion of authority.

Upon the conception of the theory, the great replacement belief was mainly supported by far-right extremist groups. The information about the conspiracy theory gets primarily distributed online which eventually contributes to the process of ‘mainstreaming the fringe’ (Barkun, 2016). Although the posts and videos containing radical content concerning the white genocide get frequently deleted from the Web, it often reappears on new accounts and gets shared among users. At the end of the day, the rhetoric finds its way to reach top tv channels and news reports, such as Fox News. The conspiracy theory also resonates globally with different local far-right groups spreading it among their followers.

The fact that the information on the white genocide conspiracy theory gets banned, serves as a confirmation of its truthfulness for its believers. The actions of social media platforms deleting the content stand in line with the rhetoric of ‘stigmatized knowledge’, namely ‘the elites do not want us to know’, therefore it must be accurate. Suspicion of authority is one of the key factors to why conspiracy theories like the one of the great replacement, get their broad circulation online and offline (Barkun, 2016).

Political consequences

The white genocide conspiracy theory can be regarded as a part of the ‘post-truth politics’ in which non-mainstream narratives of political significance get spread by ‘countermedia’ (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). Online activism also plays a role as one of the key ways to spread alternative information and setting far-right and anti-immigration scenes (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

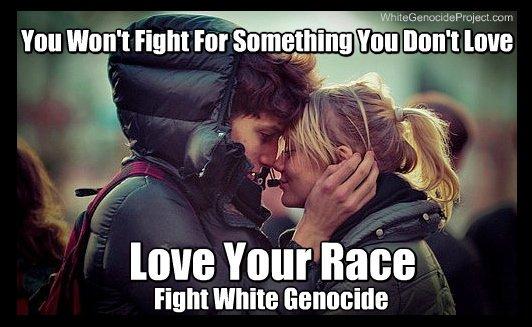

Figure 6: The call to 'love your race' and 'fight white genocide' implying the choice towards 'blood purity'.

Encouraged by the 2015 ‘migrant crisis’, ‘countermedia’ websites started spreading politically charged news all around Europe (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). They were accusing “immigrants of serious crimes, mainstream journalists of covering them up, and politicians of facilitating a destructive assault” on the Western society (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). The countermedia reports were fueling the political climate by “most often cherry-picking, colouring, and framing information to promote a radical anti-immigrant agenda” (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

The white genocide conspiracy has contributed to populist rhetoric. The belief contests epistemic authority by claiming that “‘the common people’ have had ‘enough of experts telling them what to do’, and that it is the ‘common people’ who have access to practical knowledge via their everyday experiences, from which the experts have become estranged” (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). The belief is still referenced by politicians reinforcing stricter immigration policies on behalf of ‘the people’ against ‘evil elites’ (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

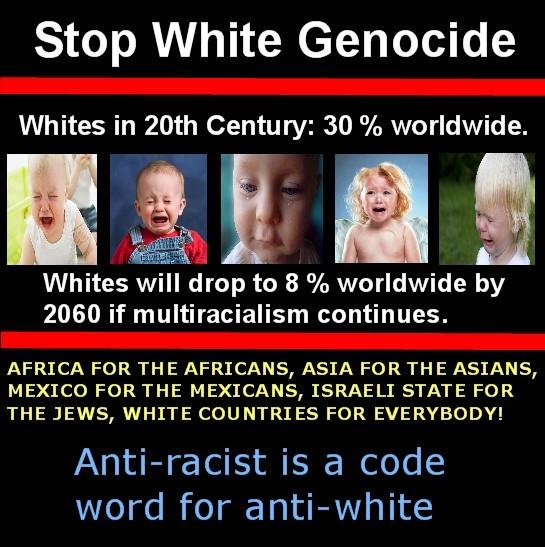

Figure 7: Reinforcing the message by using the pictures of crying white babies.

Because the great replacement conspiracy theory content gets frequently banned online and has to be reshared by marginal groups, it creates an aura of counterknowledge. The danger is that it is regarded as 'alternative knowledge' which "challenges establishment knowledge, replacing knowledge authorities with new ones, thus providing an opportunity for political mobilization” (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

From being a marginal conspiracy theory, the great replacement belief plays a role in both ‘epistemological populism’ and counterknowledge. The theory challenges the authority of the political elites, as well as knowledge elites (Ylä-Anttila, 2018), offering alternative viewpoints and contributing to the global far-right movement. In the moments of civil unrest, the conspiracy theory can be used as a common reference for the populist mobilization of the masses.

Figure 8: The slogan distributed online on the white genocide-dedicated websites.

The white genocide conspiracy theory challenges the ‘mainstream knowledge’ (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). Research in social psychology shows that these sorts of beliefs undermine knowledge authorities by overshadowing “any actual evidence in a social and political context” (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). In addition, “the more seriously conspiracies are taken, the less trust can be placed in the centres of authority” (Barkun, 1994). The spread of the conspiracy theory provokes the belief that no institution can be trusted (Barkun, 1994) and that the truth lies in the alternative streams of information that should be followed. While searching for alternative sources, populist framing takes place, bombarding the person not only with the great replacement theory but also with additional information radicalizing their views on politics, migration, abortion, minority rights, and the LGBTQ+ community.

The white genocide as resistance rhetoric

Lately, there has been an emerging trend in the public sphere of acknowledging the role of ‘the other’ (Scott, 1991). The shift is happening with historians, intellectuals, and politicians significantly acknowledging the experience of minority groups. The process of uncovering experiences of minority groups, everyday histories, female history, history of LGBTQ+ serves as a justification of multiple perspectives ‘from below’ rather than one mainstream narrative everyone should adhere to (Scott, 1991).

The discussion and the discursive meaning of ‘experience’ are political (Scott, 1991). The term is used to highlight similarities and differences, to claim unassailable knowledge (Scott, 1991). Focusing on the experience of ‘the other’ refigures history, reshapes the role of historian, and opens novel ways of thinking about change (Scott, 1991).

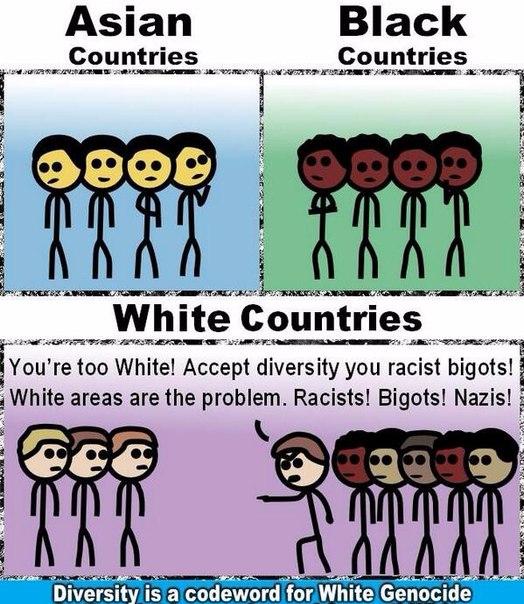

Figure 9: The meme fueling racism by victimization and a call to act via the explanation 'Diversity is a Codeword for White Genocide'.

Seeing more points of view in the public sphere instead of the predominant white ‘Western’ narrative, many people appear to feel personally threatened. The circulation of the white genocide conspiracy theory becomes one of the defense mechanisms of the group. However, what it signifies is a surface of the problem of systematic exclusion of the ‘other’ narratives from the public sphere.

Algorithmic boost

Algorithms play an important role in the spread of the great replacement conspiracy theory. They distribute content, selecting what information would be the most relevant to us (Gillespie, 2014). Once appearing in the filter bubble with rhetoric promoting the white genocide conspiracy theory, the user can get a lot of automatically generated information confirming his or her beliefs.

Algorithms have become “a crucial feature of our participation in public life” (Gillespie, 2014). The algorithmic assessment of information produces and certifies knowledge, representing a particular knowledge logic (Gillespie, 2014). This logic is built upon specific assumptions about what is most relevant for a particular individual based on his/her online interactions (Gillespie, 2014).

Figure 10: Often, believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory goes together with certain political views. The meme features '@americafirst' tags, calling 'Stupidliberals', 'MAGA',.

Interaction with the white genocide discussion may link to the far-right information channels, reinforcing a particular informational ecosystem. This has consequences in reposting and sharing the conspiracy theory content to broader publics which eventually may lead to political consequences with the theory gaining more followers. The white genocide concept becomes a bridge leading internet users to more radicalized political beliefs which they recreate online and offline.

Conclusions: hidden threat or political manipulation?

Conspiracy theories have a risk of being treated like truthful alternative knowledge. The great replacement conspiracy theory contributes to the far-right rhetoric of white populations worldwide. Depending on the country, a conspiracy theory can adjust to the context of the locals, such as in the case of Russia.

Although the content with the white genocide conspiracy theory gets frequently banned online on the mainstream social media platforms, the belief finds its way around the community with the help of the reposts of users. The aggressive policy of the platforms towards deleting the content only makes the conspiracy theory more credible in the eyes of those who believe in it. By looking at the great replacement conspiracy theory, we can see how a piece of stigmatized knowledge moves from what is recognized as ‘the fringe’ to the mainstream media (Barkun, 2016) via Fox News, politicians' interviews and tweets, and public intellectuals working on supposed solutions to prevent what they frame as white genocide.

References

Barkun, M. (2016). Conspiracy theories as stigmatized knowledge. Diogenes, 1-7.

Barkun, M. (1994). Religion and the racist right: The origins of the Christian identity movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In Gillespie, T., Boczkowski, P.J., & Foot, K.A. (eds.) Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality and society. MIT Scholarship Online, 167-193.

McCann Ramirez, N. (2020). A racist conspiracy theory called the 'great replacement' has made its way from far-right media to the GOP. Business Insider.

Sexton, D. (2016). Non! Spectator Life. The Spectator.

Vdovychenko, N. (2019). Slavic Union is on the rise in Eastern Europe. Diggit Magazine.

Ylä-Anttila, T. (2018). Populist knowledge: ‘Post-truth’ repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 5(4), 356-388.