White terrorism, white genocide and metapolitics2.0

Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the white nationalist terrorist attack in New Zealand, saw himself as a crusader for the white race, a white terrorist stepping in the footsteps of Breivik. This battle has an offline and an online dimension and it is crucial that we take this online/offline nexus on board when analyzing contemporary white terrorism.

White terrorism as a sociocultural construct.

Terrorism, in common day parlance, is rarely associated with ‘us’. In the last decades we were trained to understand terrorism as something that was exclusively associated to ‘them’, as the thing Muslims do.

If an extreme-right activist did engage in murderous riots, he or she would be framed as a lunatic or a lone wolf. Think of Breivik, Dylann Roof in Charleston, or Gregory Bowers shooting up a Synagogue in Pittsburg. Analytically speaking, this reasoning is inadequate if we want to understand contemporary radicalization and the rise in white natonalist terrorism.

Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the murderous riot in a New Zealand Mosque taking 49 innocent lives, defines himself in his manifesto as a crusader, a terrorist even and an eco-fascist. And he does it with pride. He sees himself, just like Breivik and Roof, as a future hero, as a soldier fighting for the survival of the blood-and soil white nation.

Dissociating the individual act from the broader social, cultural, political and technological context in which his voice is produced, causes us to miss broader picture of white terrorism.

Even though he explicitly states that he is not a member of any nationalist or political group or organization, we should be careful to label Tarrant ‘a lone wolf’. Legally speaking, yes, he probably acted alone. The Norwegian judges passing judgment on Breivik concluded that too. But if we analyze the roots and formats of acts of this kind, this labelling is inadequate to understand white terrorism as a contemporary phenomenon.

The concept of a ‘lone wolf’ comes with associations of individuals radicalizing themselves while being isolated in society. It immediately triggers the frame of ‘the freak’ with mental issues.

This individualist 'freak' -frame also has an offline bias, it makes us blind to the social, cultural, and political dimensions of these types of radicalization. The thing is, that his offline behavior had an enormous online shadow. From the moment we not only analyze the offline act, and start looking at the online, his act acquires a very different meaning.

White terrorism, 8chan and metapolitics 2.0

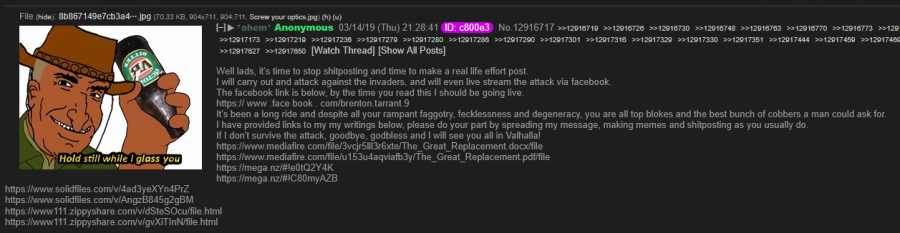

In his manifesto, on his Facebook and Twitter page and in his announcement of the terrorist attack on 8chan, Tarrant constructs an identity for himself within a globally niched new right and extreme right culture. If we analyze the announcement of his raid on 8chan, it becomes obvious that he saw himself as ‘amongst friends’ who he not only knew but also shared time with. His use of the 8chan lingo indexes that he was indeed, as he himself mentions, a longtime member of this online community.

Even more, he saw his fellow anons as ‘fellow crusaders’ in a battle to save the white nations of the world. He saw it as their duty to start spreading memes and engage in shitposting to spread his message further. What looks like an individualist action offline, has clear social-cultural and political online dimensions. He acted offline as an individual who has made the choice by himself, but also imagined himself as a Knights Templar warrior and a member of several polycentric and transnational white nationalist networks.

These practices are best understood as metapolitics 2.0. It is metapolitics that is not only about the production of ideas, but also about digital literacy.

8Chan was clearly one center to which Tarrant oriented. The fact that he speaks the language and understood the rules of online practices show the degree to which he was a member of this group. This group engaged in metapolitical action. They produced memes, engaged in meme warfare, shitposting and trolling for a metapolitical reason: to launch and normalize radical right ideas (Nagle, 2017; Maly, 2018).

Just like the old metapolitics of the 20th century extreme right school of thought, La Nouvelle Droite, contemporary metapolitics is set up as right-wing gramscianism. What has changed is the methods and infrastructures that are being used. Memes, trolling and shitposting are the metapolitical practices of the 21 century. These practices are best understood as metapolitics 2.0. It is metapolitics that is not only about the production of ideas, but also about digital literacy. In the 21st century, the ideological battle aimed at stretching the overtone window and normalizing far right ideas is waged online. It uses the algorithms and interfaces of the digital environment in order to push ideas of white nationalism, white genocide and the great replacement.

Just like Dylann Roof, Brenton Tarrant designed his terrorist attack for uptake. The act was announced on 8chan, he set up a Facebook account and a Twitter-account on 12 March to generate attention and uploaded his manifesto. He even made a soundtrack out of extreme-right video memes which became the beat to his livestream of the mosque shootings - a soundtrack that was heavily discussed on 8chan during his livestream by anons who got the references.

The riot was not just a riot, it was set up to draw attention to the perpetrators ideology and their cause. 'Dylann Roof ended his manifesto, with the claim that he hoped that it would make white people become racially aware and that his acts would spark the anticipated race war. Laqueur, already in 1977, stressed that terrorism only works if there is media-attention.

In the 21st century, terrorists stage their uptake and media-attention. Tarrant, just like Breivik, even interviewed himself at great length in his manifesto, thus preformulating the news and providing answers to questions, even in the event of his death. In a hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2017), white terrorists use digital media and offline action to draw attention to their cause.

Breivik, the Knights Templar and the alt-right

Another center to which Tarrant orients is Anders Behring Breivik. He wrote: “I only really took true inspiration from Knight Justiciar Breivik.” Tarrant’s manifesto, in form and content, shows remarkable resemblance to the manifest of Breivik. Brenton Tarrant explicitly claims to take inspiration from Breivik and the manifest takes it main motifs from Breivik’s manifesto. He sees himself, just like Breivik, as a knight: a crusader. Not coincidently, the crusader (just like the trope of reconquista) has become an enormous popular meme within new right and far right circles.

Even more, he even claims to have contacted Breivik and ‘receiving a blessing for my mission after contacting his brother knights.’ Brenton Tarrant thus not only looks at Breivik, he imagines himself as member of the reborn Knights Templar.

If we further analyze the discourse in that manifesto, we see that his discourse also orients to contemporary alt-right discourses on white nationalism

The discourse that he uses in his manifesto is very different from the discourse we can read in his 8chan post. In that manifesto, he clearly wanted to position himself as ‘a knight’. A crusader against ‘cultural genocide’. He imagines himself fighting for ‘Millions of European and other ethno-nationalist peoples that wish to live in peace amongst their own people, living in their own lands, practicing their own traditions and deciding the future of their own kind.’ This reference to 'millions' supporting his cause is also a direct intertextual link connecting Tarrant's and Breivik's manifestos, and a constant theme in Breivikian circles.

He explicitly states that he has read and supports statements from ‘those that take a stand against ethnic and cultural genocide’ like 'Luca Traini, Anders Breivik, Dylan (sic) Roof, Anton Lundin Pettersson, Darren Osbourne etc.' We again see a social dimension here: he frames himself and his actions as part of a group of 'soldiers' and he hopes to lead by example. In his manifesto, he wants to persuade other white men to become soldiers.

If we further analyze the discourse in that manifesto, we see that his discourse also orients to contemporary alt-right discourses on white nationalism as expressed by people like Richard Spencer, YouTube channels like Red Ice or extreme right sites and publishers like Counter-Currents. He for instance frames himself as ‘an Ethno-nationalist Eco-fascist’ fighting for ‘ethnic autonomy for all peoples with a focus on the preservation of nature, and the natural order.” Again, we see how through his acts and discourse a lot of other people's voices are reproduced. And how his acts create echo-chamber uptakes, for instance in an article on Counter-Currents itself.

I should be clear: dissociating the individual act from the broader social, cultural, political and technological context in which his voice is produced, causes us to miss the broader picture of white terrorism.

White terrorism, white nationalism and digital media

This framing of himself and his action is clearly not an individual construct, it is a social fact. It is constructed in collaboration with other people from different corners of the world and different timeframes. In digital culture studies, scholars have now been arguing for several years that digital media are spraces were new types of social groups emerge. These groups (light communities, micro-populations, networked or affective publics) do not necessarily share the same location, nor do they know each others name, but they do function as social groups. They produce norms and normality, and engage in structured and formatted modes of practice.

White terrorism is the most extreme manifestation of such a social group: far right white nationalists. We cannot understand white terrorism without looking at the emergence of white nationalism. It is this ideological or metapolitical dimension, embedded in YouTube channels, fora, journals, books, think thanks, memes and manifestos that explain the rationale of the terorrist and the cultural material informing his acts.

Trying to understand white terrorism within a ‘lone wolf framework’ is clearly inadequate if we want to understand and address the phenomenon. White terrorists cannot be understood if we detach their individual acts from the social and online dimensions that shaped them and generated audiences for them.

References

Chadwick, (2017). The hybrid media system. Oxford University Press.

Laqueur, (W.). (1977). Terrorism. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw rechts. Berchem: Epo.

Nagle, A. (2017). Kill all normies. Online Culture wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-right. Winchester, UK & Washington, US: Zero Books.