Spotting fake news for your media literacy

Fake news on tv, on social media, and in our newspapers, makes it seem like viral content has infiltrated every single tool of our media consumption. Despite untruthful information spreading being such a widely applicable issue, there is still a concerning low level of media literacy surrounding 'fake news' detection among the general population. This has various reasons. ‘Fake news' is like a virus, it wants to penetrate your mind and spread further to a wider population, causing doubt, political mistrust, or simply exceeding advertising revenue.

The strongest tools of fake news

To make the spread of fake news possible, many untruthful information pieces use emotional appeal to catch attention. Humans operate similarly to each other. Strong feelings often drive our minds to be more likely to believe the information we consume. Often it is the case that, when seeing a news article that deeply shocked us, our first instinct is to share it with our friends and family.

What we see emerge here is ‘the economics of attention’ (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). The triggering content gets most spread in the media which, in turn, generates attention and viewing time, profitable for the website and its advertising revenue. This influences the media sphere in its competition for attention and becomes a reason why information pieces adopt the ‘clickbait’ nature. The most effective way for journalism, whether truthful or not, to attract attention and to become visible in excessive amounts of available content nowadays is to apply similar triggering emotional strategies. This, in turn, complicates fake news detection even further.

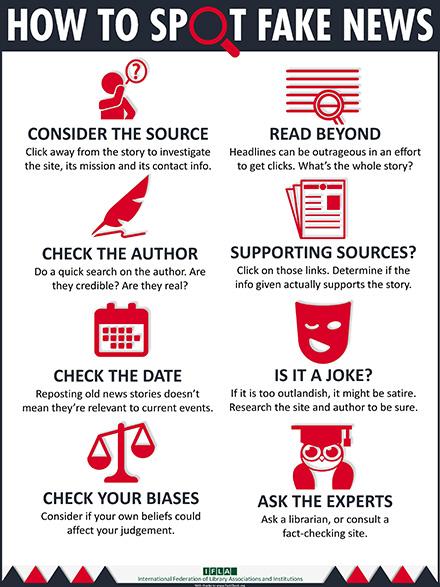

Figure 1: Some of the basic tips to filter news stories we see on (social) media.

Another problem is the structure of social media. Nowadays, we mostly consume information through our online platforms. Digital media affordances allow for endless timelines and easily accessible repost buttons. We publicly 'perform' our opinions through likes, comments, and shares (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). This social media structure influences the way we evaluate information. One can think about filter bubbles and echo chambers that trigger confirmation bias. When people hear about something a lot, they are more likely to perceive it as true, even if it initially contradicted their prior knowledge (Fazio, et al, 2015). However, this is only a part of the problem.

Users are driven to share content because of the feeling of belonging and ‘tribal’ mentality (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). As an active social media user, you do not want to miss out on reposting a seemingly interesting piece of information you have noticed your friends share. In this way, online platforms facilitate the recontextualization of news stories within their digital space, rather than as a part of an independent news outlet (Winter et al, 2015). To better understand this issue, one can think about famous websites generating fake news that became internet famous when being reposted on social media without paying specific attention to where this piece of information came from. By seeing our friends repost content, we are less likely to check it. Because we trust the user, we do not think of a fact-check as our primary reaction.

Is it fake news, junk news, misinformation, or disinformation?

What could be the solutions to this intensifying problem of the ‘fake news’ spread? While we still have to wait for AI advances in false information detection and the penalization of media sources spreading hoax news is a subject of political speculation, increasing digital media literacy seems like an attractive, and the most feasible solution.

First of all, there comes a problem of definition. We need to reconsider whether we still want to call the false information in the media ‘fake news’. Let us be honest, the term has been subject to political manipulations, and by becoming widely applied by populist parties it does not represent what it originally stood for. Some scholars propose the term ‘junk news’ because audiences consume such media pieces for self-satisfaction; the information is addictive but not relevant (Venturini, 2019). Terminology definition is a part of the plan of improving digital literacy. The junk news perspective gives us better weapons to defend ourselves against unwittingly being fooled by fake news as it helps us understand the mechanisms at work behind false information spread.

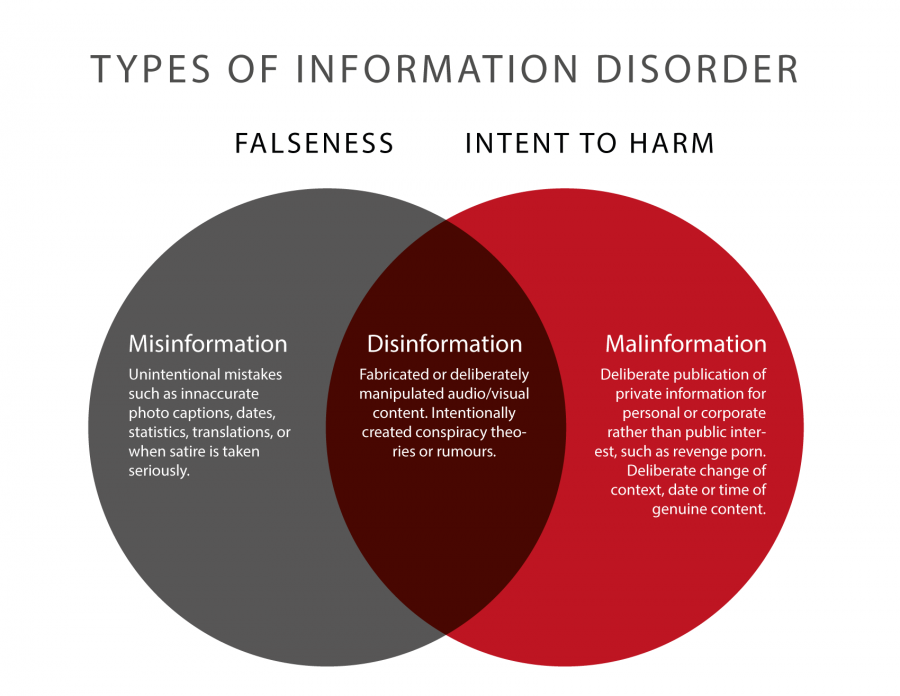

Figure 2: The differences between misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.

Secondly, fake news is an umbrella term. As media users, we need to distinguish between at least three types of false information (see Figure 2). Namely, misinformation, when misleading content is shared but no harm is meant, disinformation, when untruthful information is knowingly shared to cause harm, and malinformation, when genuine facts are shared to cause harm (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). Knowing the definition of each term can help users better detect the type of fake news they came across as it increases the level of criticism and media literacy in the population. The ability to recognize the type of false information can help distinguish the credibility of the news source, the aim of why untruthful messages were created, and 'actors' who produce and distribute a particular piece of information with or without meaning harm (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017).

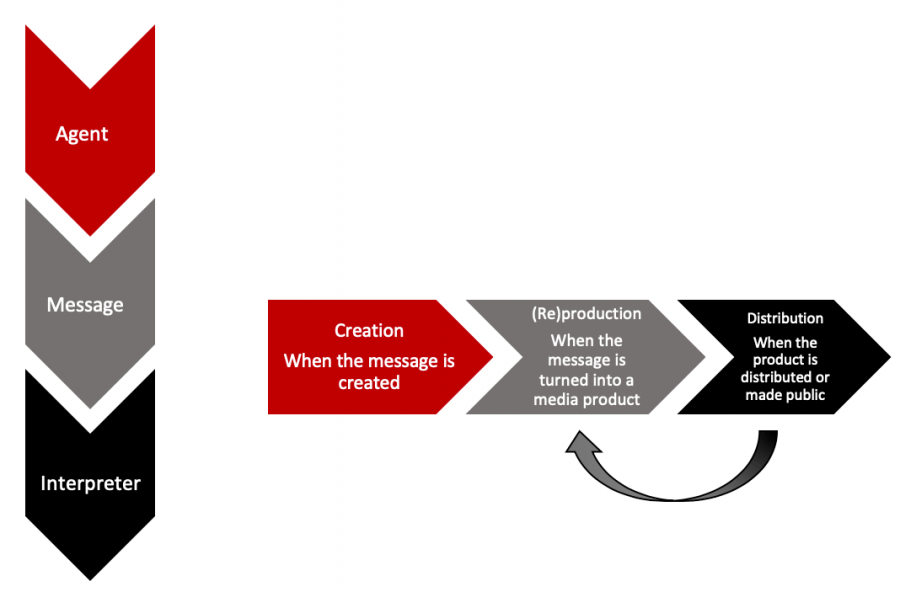

In addition, as media consumers, we need to critically distinguish the phases of fake news creation. Firstly, try to detect the agent or the author/outlet who produced the media entry. The date, place, and time of the publication and of the reported event matter as well and should be paid attention to. Then, we need to ask ourselves, what could be the possible motivation of a particular actor to distribute false information (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). Read beyond the headline and beyond the text to find out whether anything seems irrational, odd, or too sensational. The following element is the message. As careful media consumers, we need to spot vital details such as what is the format, the characteristics, and the type of message that was distributed (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). How are the claims in the piece supported? Is there a way to verify or fact-check them? The final element is interpretation. We need to learn how to spot if the information was received by someone and if so, how was the message interpreted by them, and whether any follow-up actions were taken afterward (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017).

Steps to higher media literacy

To sum up, by following these critical steps, we familiarize ourselves with the three phases of false information distribution (see Figure 3). Namely, the creation of the message, how this message is turned into a media product, and how it gets distributed to the media public (Wardle & Derakhsan, 2017). Knowing these, we can try to draw conclusions whether the piece of news was produced to saturate audience opinions, reduce the richness of public debate, shape political opinions, or prevent more important stories from being heard (Venturini, 2019).

Figure 3: The 'fake news' distribution cycle.

Overall, the false information spread problem is very drastic. In the contemporary globalized media field and changing political climate, increasing media literacy should be a strategic task among the general population. Although it is impossible to solve the problem altogether yet, increasing awareness of different types of- and the spread of misleading information, can be a vital step towards better ‘fake news’ detection.

References

Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, Keith, B., Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. APA PsycNet.

Venturini, T. (2019). From Fake to Junk News, the Data Politics of Online Virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, & E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London: Routledge.

Wardle, C., Derakhsan, H. (2017). Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe report.

Winter, S., Brückner, C., Krämer, N. C. (2015). They Came, They Liked, They Commented: Social Influence on Facebook News Channels. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, Vol. 18, No. 8. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publishing.