Black Lives Matter: Protesting in the hybrid media system

In the midst of a pandemic, activists joined together both online and offline to protest police brutality and the death of George Floyd in summer 2020. It is exactly this online activism that showcases both the merits and downsides of the hybrid media system. What is the hybrid media system, and how did it benefit last summer’s protests?

Black Lives Matter and hybrid media

Social media is part of the hybrid media system (Chadwick et al., 2016). This system allows organisations, groups and individuals to connect with one another, albeit through a series of complex relationships. It has the advantage of sharing information quickly, yet it makes it virtually impossible to completely control online spaces such as Twitter and Instagram (Thompson, 2020). We do not control who sees our tweet and there are multiple audiences to account for.

In the case of Black Lives Matter, it is more than just a hashtag; it is also a call to action that has lead to protests both online and offline. Although we have limited control over who sees our posts, mediated online interaction allows users to bypass framing done by mainstream media (Thompson, 2020). Mediated online interaction is created by computer-mediated communication, typically via smartphone or laptop. What is key here is that this type of interaction goes both ways, between the receiver and the “broadcaster”. An example of this would be Twitter, although the relationship between different users and how they interact differs by platform.

Research would suggest that online activism can be more persuasive than simply engaging with the public offline. Modern activism has the potential to provide an unimaginable reach and has the benefit of a sense of intimacy and personalisation. In other words, people may listen to this information more closely when it comes from a source they know and trust, such as a friend or relative (Bugeja, 2019). The downside is that social media has the potential to create filter bubbles or echo chambers, leading people to understand only part of the story.

During the summer of 2020, all over the world, people joined together to raise awareness about a decades-old problem: “There have been years, decades, and centuries of state-justified and perpetuated violence against the Black community with police brutality and killing of innocent Black lives as an obvious example – at least to some of us” (Chun, 2020). Activists decided that enough was enough after the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed while being arrested by police. Videos and photos of Floyd's last moments spread rapidly online, in which he called out to his mother and was heard saying “I can’t breathe.”

A worldwide call-to-action

George Floyd's death caused worldwide outrage and was the catalyst for many Black Lives Matter protests. As Castells (2015) states, this type of activism is “usually triggered by a spark of indignation either related to a specific event or a peak of disgust with the actions of the rulers.” George Floyd was one of many police killings, including the deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, that sparked outrage amongst protesters. Throughout the protests, Instagram and Twitter became the most important places to gather information about the cause. However this would turn out to be less than ideal:

“The Black Lives Matter hashtag is being used on Instagram and Twitter to share footage from protests, links to organizations where people can donate money, and information and resources for people to either educate themselves or access help. It’s harder to get this out to people en masse if the feed is broken up with black squares.”

Blackout Tuesday was spearheaded by music executives Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang (Gonzalez, 2020): “We will not continue to conduct business as usual without regard for Black lives. Tuesday, June 2, is meant to intentionally disrupt the workweek.” Artists such as Quincy Jones urged others to set aside their work and reconnect with their community. Jones wrote: “Due to recent events please join us as we take an urgent step of action to provoke accountability and change.” Brands such as Spotify and Apple said they too would cease most operations that day in light of events.

The post in which Quincy Jones urges others to take a step back and reconnect with the community.

The problem here is not that people didn’t join the movement, but rather that it gained perhaps a bit too much exposure. Posts started showing up under #BlackLivesMatter in addition to the Blackout Tuesday hashtag. Without meaning to, as the hashtag took over the Internet.

“Visibility for different groups and activist projects are key right now."

Given that many posted their black squares without a caption, it is difficult to discern exactly why people posted about the hashtag or, more cynically, joined the bandwagon. “What began as a proposed day of reflection after the death of George Floyd morphed into something broader, leading some to complain that #BlackLivesMatter posts were being silenced” (Coscarelli, 2020).

Utilising hashtags on social media can be a helpful tool for protesters to find and engage with each other, but online spaces are often minimally mediated - anyone can add to the hashtag whenever they want. Although spreading the hashtag #blacklivesmatter was assumedly done with the best of intentions, in reality, the black squares slowly started to obscure relevant information. “Visibility for different groups and activist projects are key right now. And one of the most common ways to keep track of all of this is by monitoring or searching tags.” (Willingham, 2020).

Black squares everywhere

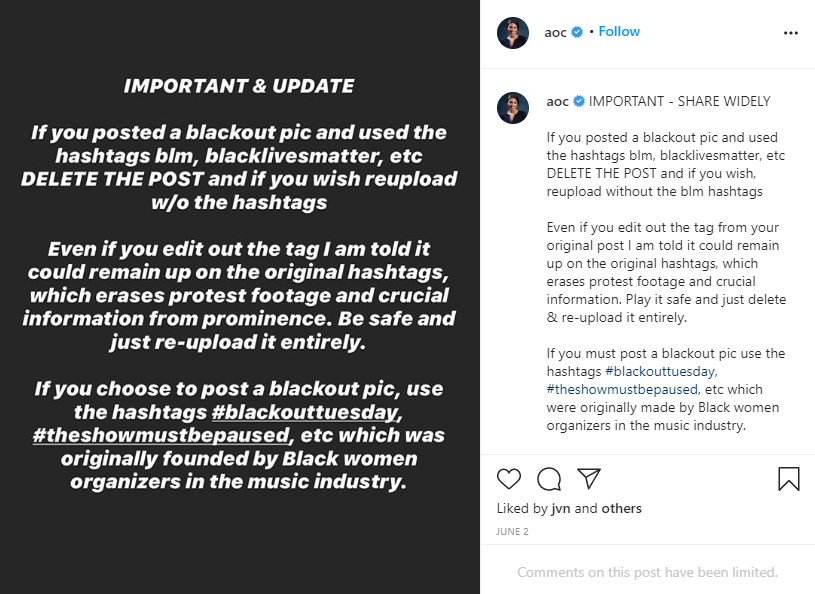

The incredible amount of black squares all over social media led to many activists asking people to stop using the hashtag. U.S. congressional representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez posted an urgent message on her Instagram, asking her followers to delete the hashtags from their black square.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez urging followers to remove the hashtags from their posts

Writer Anthony James Williams also addressed those posting content under the Black Lives Matter hashtag:

Anthony James Williams urges followers to stop posting the black squares

Williams went on to say that a black square doesn’t do much for Black people in the first place. He urged people to donate or deliver resources instead. The effectiveness of online activism has long been questioned. For instance, a reporter pointed out that when she followed the U.S. protests, many exclusively focused on George Floyd, although the intention was protest structural racism and widespread police brutality. Fondren points out that other victims, such as Breonna Taylor, had been forgotten:

“The march lasted about two hours, but it hit me about 20 minutes in that not a single chant had been created to honor the life of Breonna Taylor. In fact, it wasn’t until the tail end of the protest that her name was ever mentioned, and at that point, there was no enraged chant to commemorate her last words on earth like there had been for Floyd” (Fondren, 2020). Fondren's example could be explained by the aforementioned filter bubbles.

The cost of online activism

Online activism, and the use of social media, may come at a cost. The Internet was once considered a potential remedy for the decline in political participation (Christensen, 2011). Although social networks increase participation, they also lessen motivation, resulting in “slacktivism”. Slacktivism is a derogatory term meaning “the practice of supporting a political or social cause by means such as social media or online petitions, characterized as involving very little effort or no commitment” (Van der Veen, 2018). Black Lives Matter as a movement, with its worldwide offline protests, is not an example of slacktivism in and of itself, but rather it has attracted a number of people who post on the hashtags without participating any further.

We do not control who sees our tweet, so in a sense, there are multiple audiences to account for.

The concept of slacktivism ties in with the idea communicated by Williams, above, that simply posting the hashtag won’t benefit people as much as donating or delivering resources. “The concept generally refers to activities that are easily performed, but they are considered more effective in making the participants feel good about themselves than to achieve the stated political goals” (Christensen, 2011). Christensen argues that slacktivism by itself can create awareness through information sharing. He suggests that the problem is the lack of desire to do more despite an intention to affect political goals.

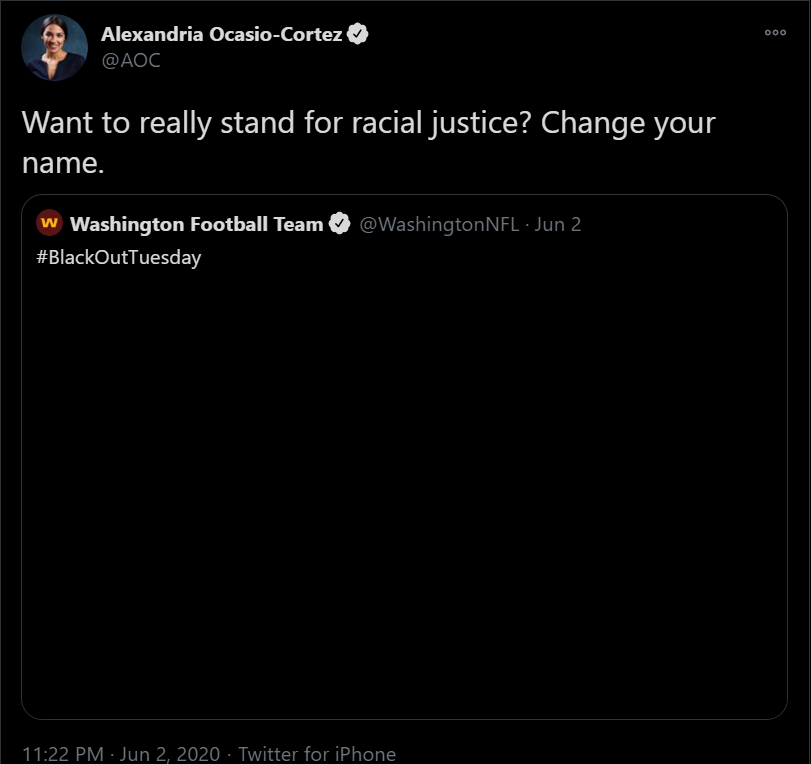

AOC calling out the Washington Football Team

In addition to slacktivism, there is also brand activism. “Brand Activism consists of business efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic, and/or environmental reform or stasis with the desire to promote or impede improvements in society.” (Sarkar & Kotler, 2018) In the wake of Blackout Tuesday, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez called out the Washington Redskins after they also shared a black square in support of Black Lives Matter. This led the football team to finally change their name, after years of criticism for using a derogatory term for and caricature of Native Americans.

Brand activism is an effective way to gain more exposure as a company: a 2018 survey showed that 64% of consumers would reward a business that showed any type of activism (Duarte, 2020). However despite the monetary gain, companies have been called out for adopting a hashtag while simultaneously having little to no black board members, and therefore coming across as inauthentic (Ritson, 2020). Unsatisfied with facile statements of support, the suggestion here is that to make a "real" difference, a company would have to change its infrastructure and make long-term plans for social inclusion and racial equality (Duarte, 2020).

AOC is seen buying shoes, after an event.

Apart from monetary gain, it is also a question of power. “Even the most powerful must cooperate with those who are less powerful, in the pursuit of collective goals” (Chadwick et al., 2016). The Washington Football Team had to change their name because they were repeatedly called out. It could be argued that as a congresswoman, Ocasio-Cortez has more power than a football team, and may have tipped the balance after years of protests of the name. “Those who have the resources and expertise to intervene in the hybrid flows of political information are more able to be powerful” (Chadwick et al., 2016). Ocasio-Cortez has something else that works in her favour: mediated online presence can lead followers to perceive a person as more authentic (Thompson, 2020). Ocasio-Cortez has cleverly used her Instagram to share not only her political thoughts but also glimpses into her personal life, and uses this authentic and personable persona to get her message across online.

Think before you tweet

The Black Lives Matter protests all across the world were certainly impressive. Through the organisers' use of the affordances of social media platforms such as Twitter, we can see that the hybrid media system allows for worldwide outrage to turn into worldwide action. Through social media people can share their experiences of racism, share useful resources, donate to those in need, or use their platform to potentially change things for the better.

Online activism has its merits in that it increases political participation, but it can also result in information overload, like what happened on Blackout Tuesday. It is incredibly difficult to control online spaces like Twitter and Instagram, so all we as users can do is listen to those in the know. A case such as Blackout Tuesday shows us the consequences of filter bubbles, brand activism, and slacktivism. In all instances, it shows us that a lack of information can cause people to feel they are doing the right thing when in actuality they are doing quite the opposite.

IT is easier to press a retweet button than it is to go outside and join a protest or change your company’s entire infrastructure. Continuing to share the necessary resources is a good place to start. #BlackLivesMatter had the right information but was overrun by good intentions. If anything, what we can learn from #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackoutTuesday is that we should be careful what we tweet.

References

Bugeja, P. (2019). #BTM – Black Tweets Matter.

Castells, M. (2015). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. John Wiley & Sons.

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., Smith, A. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A.O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge.

Christensen, H. S. (2011). Political activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means? First Monday, 16(2).

Chun, C. (2020, June 9). Black Lives Matter and the right to protest? Diggit Magazine.

Coscarelli, J. (2020, June 2). #BlackoutTuesday: A Music Industry Protest Becomes a Social Media Moment. The New York Times.

Duarte, F. (2020, June 13). Black Lives Matter: Do companies really support the cause? BBC.

Fondren, P. (2020, June 11). The ‘Say Her Name’ Movement Started for a Reason: We Forget Black Women Killed by Police. Teen Vogue.

Gonzalez, S. (2020, June 2). Music industry leaders vow to pause business for a day in observation of Blackout Tuesday. CNN.

Ritson, M. (2020, June 3). If ‘Black Lives Matter’ to brands, where are your black board members? MarketingWeek.

Sarkar, C., & Kotler, P. (2018). What is Brand Activism? Activist Brands.

Thompson, J. B. (2020). Mediated Interaction in the Digital Age. Theory, Culture and Society, 37, 3–28.

Van der Veen, E. (2018, November 1). AfD’s online movements: activism or slacktivism? Diggit Magazine.

Willingham, A. (2020, June 2). Why posting a black image with the “Black Lives Matter” hashtag could be doing more harm than good. CNN.