How could K-pop gain fans worldwide?

Korean popular music or K-pop has fans all over the globe. It is clear that most of the fans abroad are not fluent in Korean. K-pop fans therefore need to translate the message of their idols, in order to understand what they are saying. The question arises how K-pop has been able to break the language barrier with entirely different cultures.

A brief history of K-pop

K-pop is an abbreviation of Korean popular music. It is a music genre originated from South Korea that is characterized by a wide variety of audiovisual elements. Although it includes all genres of "popular music" within South Korea, the term is often used in a narrower sense to describe a modern form of South Korean pop music. The genre draws inspiration from a range of styles and genres from the rest of the world, such as Western pop music, rock, experimental, hip-hop, R&B, reggae and electronic dance, on top of its traditional Korean roots (Laurie, 2016).

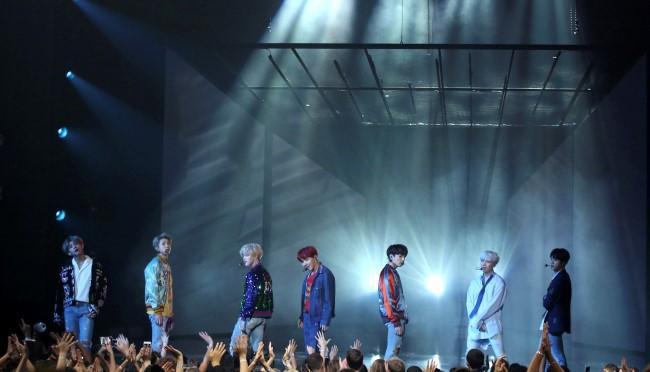

In November 2017, BTS, the K-pop boy band from Korean management company BigHit Entertainment, was invited on well-known U.S. TV shows, such as 'Jimmy Kimmel Live!' (ABC), 'Ellen Degeneres Show' (NBC) and 'The Late Late Show with James Corden' (CBS). These promotion routes seem typical for most American pop stars. The band even performed at the American Music Awards, which is one of the major annual events in the industry. After the performance, BTS grabbed No.1 on Google trends in the United States.

BTS performs "DNA" at the American Music Awards at the Microsoft Theater on Sunday, Nov. 19, 2017, in Los Angeles. (Photo by Matt Sayles/Invision/AP)

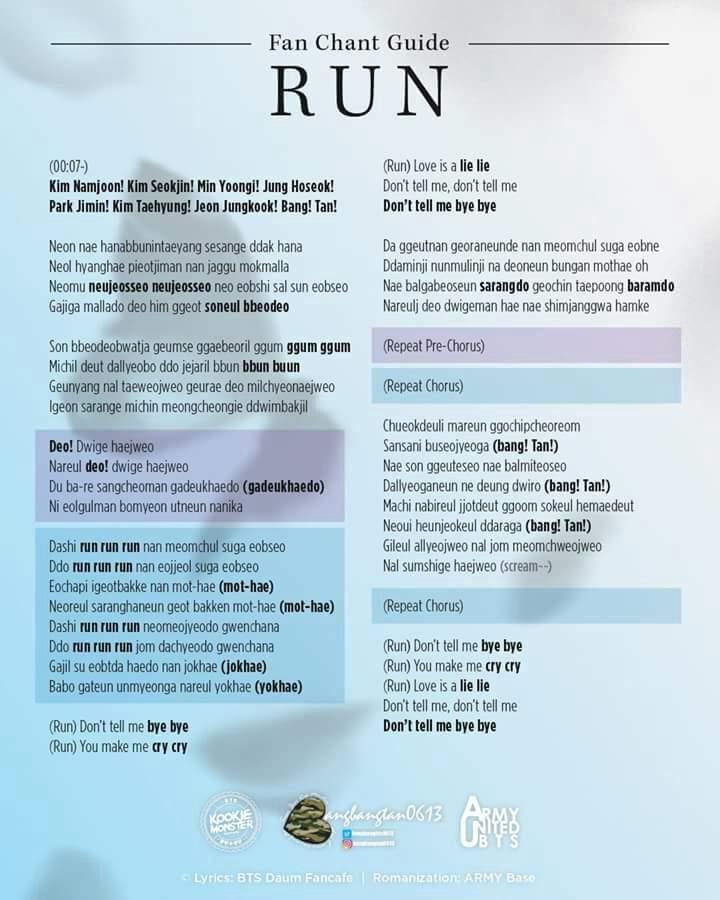

Not just BTS, but other K-pop artists as well, are continually performing worldwide. Last year, the K-pop boy band EXO had a worldwide tour and had 37 shows across Asia, North America, and even Latin America. Another hot K-pop artist, G-Dragon, had 36 shows across Asia, North America, Oceania and Europe this year. It is common to see many Facebook groups organized by international K-pop fans. Those fans memorize Korean cheer chants in English and shout out loud when their idols perform in their countries.

Search results for SHINee fan based groups on Facebook

BTS "Run" English fan chant guide for international fans (via Pinterest)

"When it comes to boy bands, the U.S. and the U.K. have historically ruled the conversation -- but not any longer. " (Benjamin & Harman, 2017)

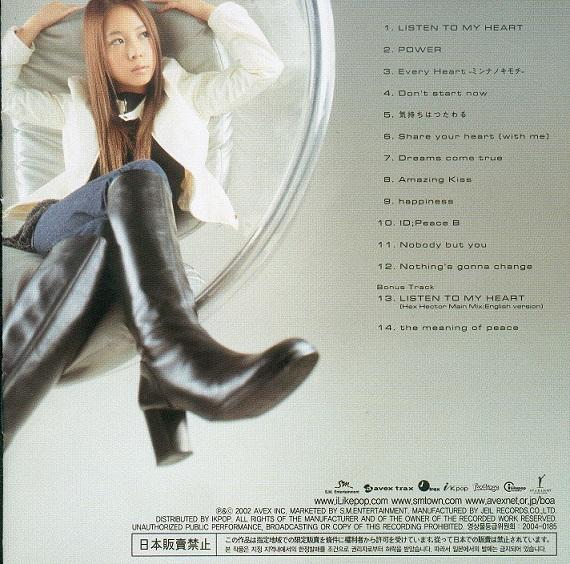

The spread of K-pop is not a new thing. Though many people from the West may have heard about K-pop thanks to PSY's 'Gangnam Style', which became a massive hit, K-pop's popularity in other Asian countries dates back about two decades. The first production company aimed at overseas markets was SM Entertainment (Lee, 2017). SM Entertainment is still the biggest music production company in South Korea. In 2000, H.O.T., the no. 1 boy band from SM Entertainment at that time, were the first to perform in China, but could not come up with a significant result. The next market to conquer was Japan. Three months after the H.O.T. concert in China, SM Entertainment debuted S.E.S. in Japan. The market for girl groups in Japan back then was already saturated with indigenous groups, so they failed again.

Japanese album of BoA "Listen to My Heart" (2009) (via Amazon Japan)

However, they didn't give up and kept trying to enter the Japanese market. This was because Japan was not only geographically close to Korea, but also had a massive market size compared to Korea. As a result, in 2001, BoA, an artist from the SM Entertainment, became the first K-pop artist to succeed in Japan. After the huge success of the BoA project, Korean music producers started to seek opportunities overseas. In consequence, many K-pop groups now have members from various nationalities and are becoming transnational commodities. K-pop could gain popularity not only in Asia, but in the West as well.

How does K-pop manage to break the language boundary?

As the genre now has fans all over the globe, it is clear that most are not fluent in the Korean language. Unlike fans of pop stars from the U.S. or the U.K. pop stars, fans of K-pop need further translation to understand what the stars are saying. The following question arises: How could K-pop manage to break the language barrier with entirely different cultures?

Appadurai (1996) asserted that “globalization does not necessarily or even frequently imply homogenization or Americanization …”. K-pop was highly influenced by Western pop music. However, its elements are not exactly the same. It has unique characteristics and those differentiate it from the Western culture. Appadurai's explanation also applies to K-pop's spread in other regions. Appadurai (1990) argues that various cultures and ideologies are brought into new societies and they tend to become indigenized in one way or another. This may explain localized versions of K-pop albums from abroad. Those albums carry the label of 'K-pop', but they are different from that which can be heard in Korea.

Moreover, K-pop can be viewed as hybridized culture, according to the scholar Jan Nederveen Pieterse. He (2015) explaineds hybridization as follows: “Hybridization is an antidote to the cultural differentialism of racial and nationalist doctrines because it takes as its point of departure precisely those experiences that have been banished, marginalized, tabooed in cultural differentialism. It subverts nationalism because it privileges border crossing.” (p. 55).

We only need to look at the way K-pop artists and companies use social media to cross borders and reach out to their international fans to see what he means.

Influence of social media on the spread of K-pop

One of the main reasons for K-pop breaking the language barrier can be found in the social media use of its artists. Interactive communications take place 24/7 all over the world. Nobody can doubt that social media play a crucial role in spreading K-pop. Since K-pop is a foreign thing, international fans have less opportunities to see their stars onh their own traditional media. So they rely on new media to get latest updates. I will discuss three social media that play a vital role in the spread of K-pop.

First, YouTube is a commonly used social platform that international fans obtain information from. It is not surprising that music lovers use YouTube a lot. You can watch the latest official music videos on it, and you can watch lots of short entertaining clips that your favorite singers are featured in. When you look at YouTube's hierarchical structure between videos, you can easily see why K-pop is doing well on the medium. YouTube's recommendation and filter system benefits heavyweight uploaders to gain more attention and, in turn, a higher amount of views. As stated by Ding and colleagues (2011):

"Uploader popularity has been tuned by YouTube intentionally by YouTube's recommendation system. On the other hand, among all uploaders, the most popular 20 percent of the uploaders attract 97.0 percent of views, which does not follow the 80-20 rule. Thus YouTube's recommendation system seems to be also biased to the very popular uploaders." (Ding, et al., 2011)

Since most artists' music videos are distributed by highly followed channels, they have high chances to be recommended, leading to high view counts. Moreover, K-pop fans also search for Korean TV shows that their stars are on. Those clips are usually edited into shorter versions than the original and fan-made subtitles are added to th

Second, Twitter is contributing a lot to the formation of fan communities. Twitter has become a platform that benefits politicians and celebrities the most. In the words of Van Dijk (2013):

"While Twitter boasts of its capability to resonate the "roar of the crowd," the platform savors the stardom of influential twitterers, especially of stars, politicians, and celebrities. Famous personalities profit from Twitter's followers' function as the perfect medium to organize and maintain their fans." (p. 75)

Fans are following accounts that specialize in K-pop, to get information such as schedules, photos, videos, and of course tweets by their favorite artists. Moreover, several fan accounts are gaining high popularity due to posting behind the scenes photos and videos they have made. Those highly followed accounts are contributing to the formation of fan communities.

Screenshot of a Twitter account that exclusively posts only photos and videos of one member of EXO

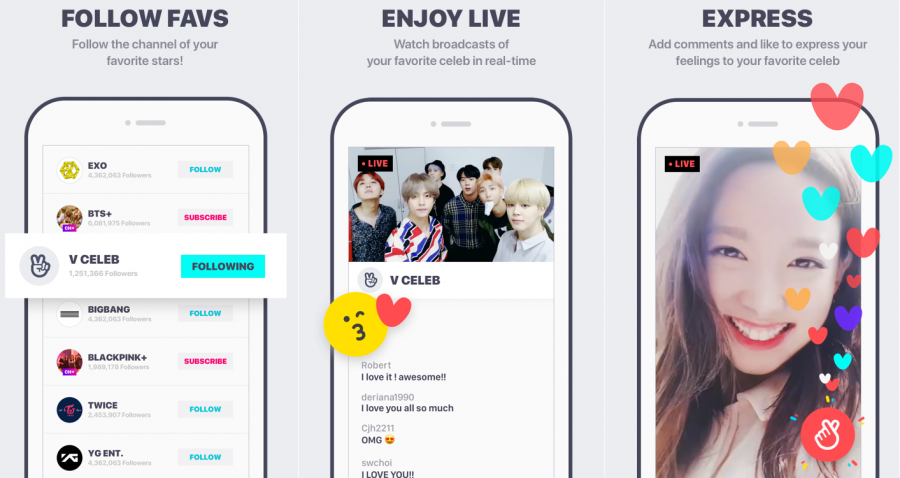

Lastly, I want to discuss the new platform V Live. It is a live broadcasting application, provided by Naver, the biggest web portal in South Korea. Users of V Live can follow their favorite stars, watch their videos, and use comments and ‘hearts’ to share their thoughts and feelings with them. Stars can turn on live broadcast whenever they want and a push alarm is sent out automatically to every subscriber all over the world. The app also supports live translation with English. After the broadcast ends, it provides a replay clip with subtitles in nine official languages.

Main features of the live broadcasting app, V Live

V Live also added V-fansubs recently, to reach users who do not speak any of those nine official languages the app currently supports for its subtitles. This allows fans to create their own subtitles. This has resulted in the app being able to translate its content in more than 55 languages. More than 72,000 fan translators have participated in this (Jin, 2017). Thanks to the great variety of languages it supports, V Live became an important medium to reach fans across the globe. In turn, the app was therefore able to obtain licenses not just for personal broadcasting, but also for broadcasting concerts, showcases and promotion events.

Non-linguistic characteristics and specifics of K-pop

A second reason for K-pops ability to break language barriers, are its non-linguistic characteristics. K-pop songs don't rely that much on Korean lyrics. They usually focus more on non-linguistic faspects, in order to have a more transnational appeal. Music videos should be fancy and up to date, and should contain a simple but nice choreography. Moreover, singers should have a pleasing appearance, and the melody of the song should be catchy. There are a few K-pop bands and songs that don't match with those characteristics, but most of the popular music in Korea follows this set of rules.

To produce trendy songs, K-pop production companies are seeking and receiving songs from composers all over the world. Renowned experts in each field of album production are recruited to raise the quality of the music. Ideas for songs are collected externally from the planning stage. SM Entertainment invites about 300 composers from around the world to participate in two conferences held annually in Korea. In this way, professionals from different countries and fields of expertise are widely employed in the production stage (Seo, 2012). This has enabled them to create lots of major hits. Nowadays, not only SM Entertainment, but also other production companies, such as Bighit Entertainment, Jelly Fish Entertainment, etc, are collaborating with producing teams and well-known DJs worldwide.

Whenever K-pop idols release a new album, they also have to create new choreography that can represent the songs they put out, in the music videos accompanying them. You can easily find videos that teach new dance moves for a song. This is very important for the genre, as the mainstream of K-pop is based on dance music. Like the effort with making songs with international producing teams, productions look for foreign dance crews or choreographers to create original dance moves. Pproductions also put a lot of of effort into making a splendid music video with good choreography, as the amount of times a video has been viewed is often used as an index for worldwide popularity.

"The essentials of producing chart-topping K-pop hits includes several facets such as having spectacular dance routines, musical and visual elements. There is also the nod to bubblegum pop with the use of colorful props and costumes." (Dimitrijevic, 2015)

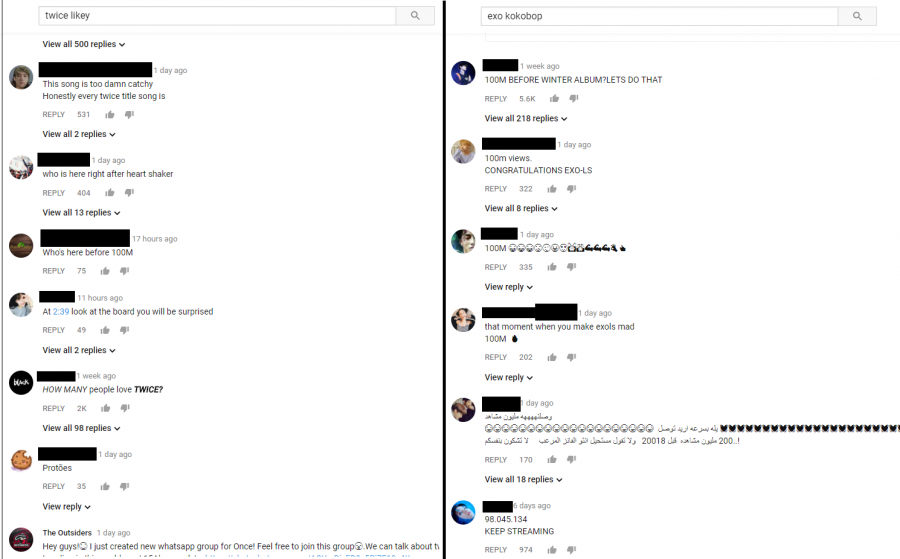

These facets are condensed into the music video and are uploaded to YouTube to engage with global fans. If we have a short glance at the comment section for these videos, we can hardly find Korean comments.

Screenshots of the YouTube comments from the music video of Twice 'Likey' and EXO 'Kokobop' respectively

Appearance

Attractive looks are essential for a debut as a K-pop idol. Not only do companies train artists' vocals, dance moves, and foreign language skills before their debut, they also manage their appearances by making them visit lots of beauty shops or even, if its needed, letting them undergo plastic surgeries. Some are pointing out skeptically that this ready-made system of idol groups has gone too far, but they are inevitable in order to to survive in the market.

"Everything, from their vocals to their face shape, is manufactured by their management companies. Cosmetic surgery is a large part of creating the K-pop image." (Stone, 2017)

Linguistic characteristics and specifics of K-pop

A final reason has to do with the linguistic characteristics of K-pop. It is not true that K-pop doesn't pay attention to language issues. Many K-pop artists are mixing English in their Korean lyrics. Moreover, when K-pop groups release albums abroad, especially in Japan and China, they are releasing indigenous language versions of their songs as well.

K-pop songs have been using English phrases for a while now. As pop music has risen from the West, it was once considered to be trendy to use English. This has become a custom and nowadays English is also used for the purpose of attracting International fans. English phrases are mostly used in the rap part of the song, or in hooks in the refrain or chorus. A hook is a musical idea, often a short riff, passage, or phrase, that is used in popular music to "catch the ear of the listener" (John, 2005). In some cases, those English phrases are grammatically wrong or mean absurd things that in turn sound weird. The YouTube clip below is satirizing those moments.

As we can see in the video, there are some misusages, however, these hooks help attract listeners, especially non-Korean ones.

As a strategy to overcome cultural barriers, localized versions of albums are released and local tastes and cultures are reflected in the lyrics, music videos and fashion. As a result, K-pop songs recorded in the local language are often used in local TV dramas, advertisements, and films (Seo, 2012). EXO, for instance, is divided into two groups EXO-K and EXO-M, which means EXO Korean and Mandarin. EXO-M consists of Korean members and several Chinese members. Normally, they all perform together, but sometimes they are split and perform in each region. Therefore, EXO's album has two versions of tracks, Korean versions and Chinese versions. Moreover, when they perform in Japan, they also release Japanese versions of their songs However, those non-Korean language versions of songs are confined to only Chinese and Japanese. This might be due to the significance of these countries' market sizes. Before their debut, members are trained to speak at least one foreign language at a native level.

K-pop as a transnational product

In this paper, I asked the question of how K-pop could manage to break through language boundaries. First, I introduced a short overview of the recent and historical background of K-pop. Then I analyzed how K-pop could spread worldwide, despite language barriers. I did this by exploring the influence of social media, and non-linguistic and linguistic aspects of K-pop. By doing this, I have shown that K-pop's spread abroad has come about in a strategic manner. However, this article mainly deals with mainstream Korean popular music, especially the idol music. Therefore, it might not be applicable for other Korean artists.

Moreover, K-pop's success abroad can be further explained by referring to Appadurai (1990), who argues that various cultures and ideologies are brought into new societies and become indigenized somehow. This is where the localized versions of K-pop that are released abroad come into play. These versions play into local markets and cater to the wishes of local fans, who may very well not speak Korean. These albums carry the label K-pop, but differ from what can be heard in Korea. In its catering to international wishes, the genre has become what Nederveen Pieterse has called hybridized culture.

As we can see above, K-pop has become a transnational product due to the multicultural background of the production system. Though the genre is called K-pop, the contents themselves are not relying on nationalism anymore. It attracts fans from all around the world, regardless of languages and national identities.

References

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Middlesbrough: Theory, Culture and Society.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large : Cultural dimensions of globalization (Public worlds, v. 1). Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press.

Associated Press. (2017, November 19). Musicians unite at AMAs in wake of tumultuous year. Dailymail. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Avexnetwork. (2017, May 15). EXO-CBX / JAPAN DEBUT MINI ALBUM「GIRLS」全曲ダイジェスト試聴音源. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Benjamin, J. (2016, March 5). K-Pop Concerts Continue to Grow Outside Asia: Exclusive Infographic. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Benjamin, J., & Harman, T. (2017, August 11). Why K-Pop Is Integral to 2017's Boy Band Renaissance. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Dimitrijevic, I. (2015, February 09). How K-Pop is Transforming YouTube. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

DramaFever. (2016, July 28). AFTER SCHOOL CLUB Ep 30 - Yerin (GFriend) Explains The Point Dances. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Fan chants for BTS songs. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Ing, Y., Du, Y., Hu, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, L., Ross, K., & Ghose, A. (2011). Broadcast Yourself: Understanding YouTube Uploaders. Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM conference on Internet measurement conference - IMC 11. doi:10.1145/2068816.2068850

Jin, H. (2017, October 10). Live Broadcasting Platforms target abroad with 'Live Translation'. Digital Times, p. 13.

Jypentertainment. (2017, October 30). TWICE "LIKEY" M/V. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons,53(1), 59-68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kim, S. (2017, February 24). SM prefers international composers, Local composers for YG and JYP. OhmyNews. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Laurie, T. N. (2016). Toward a Gendered Aesthetics of K-Pop. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

Lee, J. (2017, November 07). How could SM Entertainment maintain the first place for 22years? Dong A Business Review, (227).

Lee, S. (2010, February 25). Watching idols all year round, why still great? StarNews. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Lew, K. (2017, November 20). BTS Grabs No. 1 On Google Search Trends After AMAs Performance. Soompi. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

Listen to My Heart Import. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Pieterse, J. N. (2015). Globalization and culture: global mélange. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Search Results for Shinee. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Seo, M. (2012, February 15). What Business Can Learn from K-pop for Global Strategy. Korea Focus. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

SMTOWN. (2017, July 18). EXO 'Ko Ko Bop' MV. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

SMTOWN. (2014, May 06). EXO-K 'Overdose' MV. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

SMTOWN. (2014, May 06). EXO-M '上瘾(Overdose)' MV. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

Stone, Z. (2013, May 24). The K-Pop Plastic Surgery Obsession. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: a critical history of social media. New York: Oxford University Press.

V – Live Broadcasting App - Android-apps op Google Play. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2017.

V Live Fansubs. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2017.

WISH BOY. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2017.

XDareDBx. (2015, April 01). 50 of K-Pop's Unintentionally Funniest English Lyrics (Part 1 of 3). Retrieved December 16, 2017.